Untitled

Impact of an Evidence-Based BundleIntervention in the Quality-of-Care Managementand Outcome of Staphylococcus aureusBacteremia

Luis E. López-Cortés,1,a Maria Dolores del Toro,1,2 Juan Gálvez-Acebal,1,2 Elena Bereciartua-Bastarrica,3María Carmen Fariñas,4 Mercedes Sanz-Franco,5 Clara Natera,6 Juan E. Corzo,7 José Manuel Lomas,8 Juan Pasquau,9Alfonso del Arco,10 María Paz Martínez,11 Alberto Romero,12 Miguel A. Muniain,1,2,14 Marina de Cueto,1,2

Álvaro Pascual,1,2,13 and Jesús Rodríguez-Baño;1,2,14 for the REIPI/SAB groupb

1Unidad Clínica de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; 2Spanish Network for Research inInfectious Diseases, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid; 3Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital de Cruces, Baracaldo; 4Unidad deEnfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitairo Marqués de Valdecilla, Universidad de Cantabria–IFIMAV, Santander, Cantabria; 5Unidad deEnfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital de San Pedro, La Rioja; 6Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba;7

Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología, Hospital Virgen de Valme, Sevilla; 8Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas,

Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva; 9Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada;10Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga; 11Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital de Torrecárdenas, Almería;12Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real, Cádiz; and 13Departamento de Microbiología and 14Departamento deMedicina, Universidad de Sevilla, Spain

(See the Editorial Commentary by Liu on pages 1234–6.)

Background. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Several aspects of clinical management have been shown to have significant impact on prognosis. The objective of

the study was to identify evidence-based quality-of-care indicators (QCIs) for the management of SAB, and toevaluate the impact of a QCI-based bundle on the management and prognosis of SAB.

Methods. A systematic review of the literature to identify QCIs in the management of SAB was performed. Then,

the impact of a bundle including selected QCIs was evaluated in a quasi-experimental study in 12 tertiary Spanish hos-pitals. The main and secondary outcome variables were adherence to QCIs and mortality. Specific structured individu-alized written recommendations on 6 selected evidence-based QCIs for the management of SAB were provided.

Results. A total of 287 and 221 patients were included in the preintervention and intervention periods, respective-

ly. After controlling for potential confounders, the intervention was independently associated with improved adher-ence to follow-up blood cultures (odds ratio [OR], 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.78–4.49), early source control(OR, 4.56; 95% CI, 2.12–9.79), early intravenous cloxacillin for methicillin-susceptible isolates (OR, 1.79; 95% CI,1.15–2.78), and appropriate duration of therapy (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.24–3.64). The intervention was independently as-sociated with a decrease in 14-day and 30-day mortality (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, .26–.85 and OR, 0.56; 95% CI, .34–.93, re-spectively).

Conclusions. A bundle orientated to improving adherence to evidence-based QCIs improved the management of

patients with SAB and was associated with reduced mortality.

Keywords. Staphylococcus aureus; intervention; bacteremia; bloodstream infections; clinical management.

Received 14 March 2013; accepted 17 June 2013; electronically published 8

August 2013.

aPresent affiliation: Unidad Clínica de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Microbiología

Clínica y Medicina Preventiva, Hospitales Universitarios Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, Spain.

Clinical Infectious Diseases

bOther authors from the REIPI/SAB group are listed in the Acknowledgments.

The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Infectious

Correspondence: Jesús Rodríguez-Baño, PhD, MD, Unidad Clínica de Enferme-

Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please e-mail:

dades Infecciosas y Microbiología, Avda Dr Fedriani 3, 41009 Sevilla, Spain

DOI: 10.1093/cid/cit499

Evidence-Based Bundle on SAB • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • 1225

Staphylococcus aureus is an important human pathogen and

At present, many tertiary hospitals develop active "bactere-

one of the leading causes of both nosocomial and community-

mia programs," in which infectious diseases specialists and

onset bloodstream infections worldwide ]. Staphylococcus

clinical microbiologists provide early unsolicited advice for the

aureus bacteremia (SAB) causes significant morbidity, mortali-

management of patients with bacteremia. Despite this, the spe-

ty, and healthcare costs; complications are frequent, and mor-

cific difficulties inherent to management of SAB may need ad-

tality ranges from 20% to 40% [Importantly, some aspects

ditional interventions. The objectives of this study were (1) to

of clinical management have been associated with better out-

identify evidence-based quality-of-care indicators (QCIs) for

comes [Thus, previous studies showed that adherence to

the management of SAB; and (2) to evaluate the impact of an

specialized advice is associated with improved management

intervention based on a bundle of selected QCIs aimed at im-

and, in some of them, even reduced mortality [In these

proving the management and outcome of patients with SAB.

studies, the management and outcomes of patients with SABwho were treated following the recommendations of infectious

diseases specialists were compared with those of patients forwhom specialized consultation was not sought or where the

Identification of Quality-of-Care Indicators for the Management

recommendations provided were not followed. The recommen-

dations provided by specialists in these studies were not struc-

A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify

tured and/or had not been prioritized in accordance with an

the best evidence on aspects related to the clinical management

of SAB that had a significant influence in prognosis. Studieswere retrieved from the PubMed database using the followingsearch terms: Staphylococcus aureus OR S. aureus, AND bacter-emia OR bloodstream infection OR sepsis, AND outcome OR

Preintervention and Intervention Activities Performed

on Patients With Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia in the Partic-

complication OR mortality OR death OR recurrence. Observa-

ipating Hospitals

tional and randomized studies were selected if the 2 followingcriteria were fulfilled: the predictors or risk factors for outcome

determinants (including rates of clinical cure, microbiological

Early report (verbal or written) of Gram stain

cure, mortality, complications or recurrence) were studied, and

results was provided for all patients with

accepted methods for control of confounding were used in the

positive blood cultures by clinicalmicrobiologists in 6 of the 12 participating

case of observational studies (including multivariate or strati-

centers. Seven centers had an active

fied analysis or matching). The studies were reviewed by 2 in-

"bacteremia program" in which unsolicitedconsultation for all SAB cases of BSI were

vestigators (L.E.L.-C. and J.R.-B.). The variables independently

provided by infectious diseases subspecialists;

and consistently (eg, they were found in at least 2 studies)

neither the recommendations provided nor the

related to outcome and amenable to clinical intervention were

follow-up procedures were structured, but weredone at the discretion of the infectious diseases

selected as QCIs; for each of them a formula to measure the

subspecialist. Adherence to recommendations

level of adherence to the indicator was defined.

was not prospectively measured.

1. The intervention was explained to the different

services in specific educational sessions. An

Intervention: Study Design and Setting

informative letter was also sent to all heads of

The intervention study was performed in 12 tertiary hospitals

services before the intervention period started.

in Spain; 8 of them are teaching hospitals, and 10 have >500

2. Specific recommendations, based on the 6

selected quality-of-care indicators, were

beds. There are infectious diseases services or units in all 12,

specifically provided at least 3 days per week by

and active transplantation programs in 4. A quasi-experimental

an infectious diseases specialists from the day

design, before (from January through June 2010) and during

S. aureus was identified from blood culture untilthe patient was discharged or died. The

the implementation of the intervention (from July to December

recommendations were discussed with the

2010), was used; in one hospital where the intervention was

attending physician and were also provided in astructured form which was added to the charts

piloted, the preintervention and intervention periods were

and signed by the

from March 2008 to August 2009, and from September 2009 to

infectious diseases specialist at each visit.

Adherence to the recommendations was at the

May 2011, respectively. All episodes of SAB involving admitted

discretion of attending physician.

patients >17 years of age were considered eligible. Patients were

3. The form also included a summary of the

detected through daily review of microbiology reports. Only 1

rationale for the intervention, which served aseducational material.

episode per patient (the first) was included, unless a laterepisode was separated from the previous one by an interval of

Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; SAB, Staphylococcus aureusbacteremia.

>3 months without evidence of recurrence from a deep-seated

1226 • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • López-Cortés et al

Definitions of Quality-of-Care Indicators for Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Selected After Systematic Review of the

Follow-up blood cultures

Performance of control blood cultures 48–96 h Patients in whom follow-up blood cultures

[9–11] [14] [15] [21]

after antimicrobial therapy was started

were collected ×100/patients alive

regardless of clinical evolution

Early source control

Removal of nonpermanent vascular catheter

Patients in which the amenable source

whenever the catheter was suspected or

was removed in <72 h ×100/patients

confirmed as the source of SAB, or drainage

with source amenable of removal/

of an abscess in <72 h

Echocardiography in

Performance of echocardiography in patients

Patients with echocardiography ×100/

[9] [10] [12–15]

patients with clinical

with complicated bacteremia (see definition

patients with complicated bacteremia or

in Methods) or predisposing conditions for

predisposing condition for endocarditis,

alive at least 96 h

Early use of intravenous

Definitive therapy with intravenous cloxacillin

Definitive therapy with intravenous

[9] [13] [79] [81]

cloxacillin for MSSA as

(at least 2 g every 6 h or adjusted based on

cloxacillin ×100/nonallergic patients with

definitive therapy

renal function in renal failure) in cases of

methicillin-susceptible strains (allergicpatients excluded). Treatment should bestarted within the first 24 h after methicillinsensitivity was available. For hemodialysispatients, cefazolin 2 g after eachhemodialysis session was acceptable

Adjustment of vancomycin

Measurement of trough levels of vancomycin

Patients with trough level of vancomycin

[24] [59] [76–80]

dose according to trough

in patients treated for at least 3 d with this

determined and dose adjusted ×100/

antibiotic and adjustment of dose in order to

patients treated with vancomycin for at

achieve plasma trough levels between 15

and 20 mg/L in survivors

Treatment duration

Duration of antimicrobial therapy of at least 14

Patients with appropriate duration of

[10] [12–14] [21]

d for uncomplicated bacteremia and 28 d for

therapy ×100/patients alive at 14 or 28 d

complexity of infection

complicated bacteremia. Sequential oral

in cases of uncomplicated or

treatment with fluoroquinolone plus

complicated bacteremia, respectively

rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, orlinezolid was considered accepted in

Abbreviations: MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; SAB, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.

infection. Patients who died in the first 48 hours (who were not

Variables and Definitions

subject to intervention) and those patients receiving palliative

The main outcome variable of the quasi-experimental study

care for terminal conditions were excluded.

was adherence to the 6 QCIs selected, measured as the propor-

The intervention and the activities performed during the

tion of cases in which the recommended action was performed.

preintervention period are summarized in Table The inter-

As secondary outcome variables, 14- and 30-day all-cause mor-

vention consisted of a set of written recommendations accord-

tality and the 90-day recurrence rate were considered. Explana-

ing to the 6 aspects selected as QCIs provided in a structured

tory variables included demographics, type and severity of

form by an infectious diseases specialist at each hospital. All pa-

underlying conditions, acquisition type of SAB, source of infec-

tients were followed until discharge or death and were assessed

tion, severity of systemic inflammatory response syndrome at

for survival and recurrence on days 30 and 90 during a visit to

presentation ], susceptibility to methicillin, antimicrobial

the outpatient clinic or by phone call. Patient data were collect-

therapy, support therapy, and outcome [We used the

ed by a nonblinded investigator in each of the participating

Charlson comorbidity index to measure the severity of chronic

underlying conditions [validated as predictive of mortality

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hos-

among patients with SAB Acute severity of illness was as-

pital Universitario Virgen Macarena, which waived the need to

sessed using the Pitt bacteremia score, measured retrospectively

obtain written informed consent from the patients on the un-

on the day before SAB was diagnosed, which has also been vali-

derstanding that the intervention was aimed at improving

dated as a predictor for mortality in SAB ]. Type of acquisition

quality of care according to evidence-based standard of care.

was classified as community-associated, healthcare-associated, or

Evidence-Based Bundle on SAB • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • 1227

Microbiological Studies

The recommendations of the Spanish Society of Infectious Dis-eases and Clinical Microbiology were followed for performing,processing, and interpreting the blood cultures ]. Sus-ceptibility testing was performed using accepted methods ateach hospital.

Statistical Analysis

Crude comparisons were performed using the χ2 or Fisherexact tests for percentages, as appropriate, and the Mann-Whitney

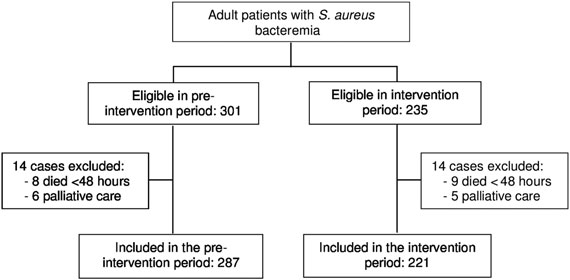

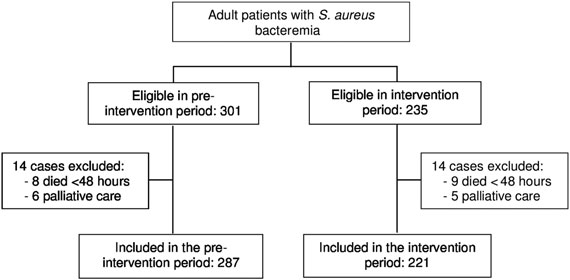

Flow chart of patients included in the multicenter quasi-

U test for continuous variables. Relative risks with

experimental study.

95% confidence intervals (Cis) were calculated for the crudeanalysis of adherence to the indicators in the preinterventionand intervention periods. Multivariate analyses were performedusing logistic regression. Variables were selected using the

nosocomial, following Friedman criteria [Primary sources of

backward stepwise procedure; P values <.2 and <.1 were used as

SAB were defined according to the Centers for Disease Control

cutoffs for including and deleting variables in the models, re-

and Prevention [], and evaluated in consensus by 2 investiga-

spectively. The predictive ability of the models was studied by

tors in each on the participant centers. Sources of SAB associated

the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves.

with high mortality in previous studies were classified as high-risk

Effect modifications between the exposure of interest and other

sources; these included endocarditis, endovascular infections other

variables were investigated. The software used for the analysis

than catheter-related, central nervous system infections, intra-

was the SPSS v17.0 package.

abdominal infections, and respiratory tract infections [, We considered empirical antibiotic treatment as appropriate if

at least 1 active drug according to in vitro susceptibility resultshad been initiated in the first 12 hours after the blood culture

Systematic Review and Definition of Quality-of-Care Indicators

was obtained. Persistent SAB was defined as the isolation of S.

The search strategy retrieved 2828 articles. After reviewing the

aureus in blood cultures obtained from peripheral veins for ≥3

abstracts, 184 articles were fully reviewed and 81 were selected

days despite active antimicrobial therapy according to suscepti-

according to the preestablished criteria (see references in

bility testing. For the purpose of clinical decisions, SAB was

Six aspects of clinical management from 16

considered as complicated if any of the following criteria were

articles showing an impact on outcome were selected as QCIs

present: persistent bacteremia; development of endocarditis or

(Table performance of follow-up blood cultures; early

metastatic foci; presence of Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, or

source control; performance of echocardiography in patients

other cutaneous or mucosal lesions suggestive of acute systemic

with specific criteria; early use of intravenous cloxacillin in

infection (including petechiae, vasculitis, infarcts, ecchymoses,

cases of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (or cefazolin

pustules, Roth spots, or conjunctival hemorrhage) in the

in patients under hemodialysis) as definitive therapy in nonal-

absence of a firm alternate explanation [presence of any per-

lergic patients; adjustment of vancomycin dose according to

manent prosthetic device; any device-related infection where

trough levels; and provision of an appropriate duration of

the device could not be removed in the first 3 days; and SAB in

therapy according to the complexity of infection. The defini-

patients under chronic hemodialysis [, ]. We included

tions of QCIs and the formulas used to measure them are

the variable "unfavorable clinical course" to reflect the clinical

shown in Table .

situation in the same day the intervention was started (typically,48 hours after the blood cultures were taken); it was defined

Analysis of the Impact of Intervention

as worsening or lack of evident improvement in the signs of

During the study period, 536 episodes of SAB were diagnosed

sepsis [with regard to the situation the day the blood cul-

in adult patients admitted to the participating hospitals and

tures were taken. Cure was defined as the absence of all signs

were considered eligible for the study; 28 cases were excluded

and symptoms of infection and a negative blood culture at the

(Figure so that 287 episodes were finally included in the pre-

end of antibiotic therapy []. Recurrence was defined as the

intervention period and 221 in the intervention period. The

isolation of S. aureus with the same susceptibility pattern from

baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the pa-

blood cultures or from a deep-seated focus in the following 3

tients in both periods are shown in Table . The proportion of

months after clinical cure had been reached.

vascular catheter–related episodes was higher in the intervention

1228 • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • López-Cortés et al

Features of the Patients With Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

All Patients (n = 508)

Preintervention (n = 287)

Intervention (n = 221)

Median age, y, (IQR)

Diabetes mellitus

Chronic pulmonary disease

Chronic liver disease

Intravenous drug abuse

Charlson index ≥2

Source of bacteremia

Vascular catheter

Skin and/or soft tissue

Respiratory tract

High-risk sourcea

Complicated bacteremia

Endocarditis (primary and secondary)b

Appropriate empirical therapy

Severe sepsis or septic shock

Unfavorable coursec

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

a High-risk source: endocarditis, nervous central system, abdominal, and respiratory.

b Considered only among patients for whom echocardiography was performed.

c Considered the day the blood culture results were reported as defined in the Methods.

period, whereas those related to a skin and soft tissue infection

intervention was independently associated with improved ad-

were less frequent.

herence to follow-up blood cultures (from 61.2% to 80.3% in

The crude comparison of adherence to QCIs between the

the different hospitals), source control (from 70.2% to 90.3%),

preintervention and intervention periods is shown in Table

echocardiography in patients with complicated bacteremia

Adherence significantly improved during the intervention

(from 52.8% to 73.3%), early cloxacillin in MSSA (from 56.9%

period for all QCIs except for adjustment of vancomycin dose

to 76.3%), and appropriate duration of treatment depending on

according to trough levels. All centers increased the adherence

clinical complexity (from 72.9% to 85.2%).

to at least 4 QCIs; a statistically significant improvement (eg,

Crude analysis showed a higher 14-day mortality rate in the

P < .05) to at least 2 QCIs was seen in 9 participant centers (it

preintervention period than in the intervention period (51/287

should be noted that the number of cases was low in some

[17.8%] vs 25/221 [11.3%], P = .04), whereas the difference for

centers). The median percentage of improvement for each QCI

30-day mortality was not statistically significant (64/287

and interquartile range is shown in Table To control the

[22.3%] vs 37/221 [16.7%], P = .12). Recurrence of SAB at 90

effect of potential confounders on the effect of the intervention,

days showed no significant differences (3/287 [1%] vs 2/221

we carried out multivariate analyses (Table . In summary, the

[0.9%]; RR = 0.86; 95% CI, .14–5.13; P = .87). Ninety-day

Evidence-Based Bundle on SAB • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • 1229

Adherence to Quality-of-Care Indicators

Median Improvement in

Relative Risk for

Intervention Percentage of Adherence to

1.31 (1.15–1.49)

2.83 (1.78–4.49)b

1.29 (1.13–1.49)

4.56 (2.12–9.79)c

1.38 (1.13–1.68)

2.50 (1.42–4.41)d

Early cloxacillin in

1.25 (1.07–1.45)

1.79 (1.15–2.78)e

Vancomycin dosing

1.18 (.80–1.73)

1.42 (.65–3.10)f

Treatment duration

1.16 (1.05–1.29)

2.13 (1.24–3.64)g

Data are expressed as No. (%) of patients except otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; OR, odds ratio; QCI, quality-of-care indicator.

a Adjusted ORs were calculated by multivariate analyses.

The variables included in final models were: bUnfavorable clinical course and catheter source; cType of acquisition; dCatheter source and Charlson index; eCathetersource, Charlson index and type of acquisition; fCatheter source; gComplicated bacteremia, Charlson index, and catheter source.

mortality was higher in the preintervention group, although

time to first administration of an active drug and to produce

without statistical significance (97/287 [33.8%] vs 59/162

better clinical management of sepsis [, ]. In the specific

[26.7%]; relative risk [RR] = 0.78; 95% CI, .60–1.03; P = .08).

case of SAB, some previous studies showed that infectious dis-

We then performed specific analyses to evaluate the impact of

eases specialists' consultation was associated with better man-

the intervention on 14-day and 30-day mortality. First, we per-

agement and, in some studies, with a better prognosis ]. A

formed univariate analyses of the association of different vari-

summary of the adherence to the 6 QCIs used in this study as

ables with mortality and ). The variables age ≥60

reported in previous studies is shown in

years, source other than catheter, Pitt score >2, and interven-

tion period were associated with 14- and 30 day mortality. Mul-

The use of QCIs is useful for evaluating and monitoring dif-

tivariate analyses are shown in Table ; the clinical intervention

ferent aspects of healthcare procedures. Indicators are quantita-

was independently associated with a decrease in 14-day and 30-

tive measures that should be sufficiently sensitive, specific,

day mortality after controlling for potential confounders in the

valid, and reliable to evaluate those aspects of care that influ-

multivariate analysis. The results did not significantly change

ence appropriately defined outcomes, and they should be

when the variable source was considered as polychotomous (eg,

ideally evidence based [, Management of SAB is clinical-

all the sources were included) instead of the dichotomized low/

ly challenging and has been demonstrated as importantly influ-

high-risk sources. Including the variable "preintervention bac-

encing outcome, making it a suitable process for defining QCIs.

teremia program" was not associated with mortality and did

To our knowledge, QCIs for SAB management had not previ-

not influence the impact of the intervention.

ously been established using an appropriate methodology; byusing a systematic review of the literature we were able to iden-

tify key aspects for SAB management that were amenable fordesigning an intervention.

Our study shows that a bundle intervention aimed at improving

During the intervention period, adherence to CQI was sig-

the adherence to selected evidence-based QCI indicators in the

nificantly and independently improved except for adjustment

management of SAB was effective and associated with reduced

of vancomycin dose according to trough levels, probably due to

the lower number of patients in this subset. These results dem-

The management of patients with bacteremia is complex.

onstrate that it is possible to improve the clinical management

Widely recognized important aspects of management includes

of SAB with an intervention based on quality-of-care indica-

providing early adequate support and antimicrobial therapy,

tors. We think that the use of a structured form for making rec-

identifying potential foci which should be properly and timely

ommendations, which could then be included in the medical

controlled, and active workup and follow-up to promptly

records, was crucial to achieving these results; apart from pro-

detect complications [Advice from infectious diseases spe-

viding clear and structured recommendations, the form was

cialists has been shown to reduce inappropriate treatment and

also useful for reminding the infectious diseases specialists of

1230 • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • López-Cortés et al

Univariate Analysis of Variables Associated With 14-

Univariate Analysis of Variables Associated With 30-

2.26 (1.30–3.92)

2.52 (1.55–4.11)

1.34 (.66–2.72)

1.41 (.75–2.63)

2.20 (1.40–3.44)

1.76 (1.10–2.82)

1.02 (.58–1.81)

0.09 (.58–1.12)

2.09 (1.22–3.59)

4.37 (2.28–8.39)

1.52 (.99–2.34)

1.44 (.63–3.27)

3.67 (2.27–5.93)

0.86 (.40–1.86)

3.63 (2.28–5.78)

2.13 (1.48–3.04)

1.65 (.84–3.10)

Complicated bacteremia

0.86 (.54–1.36)

Complicated bacteremia

1.02 (.67–1.54)

Empirical treatment

1.11 (.78–1.57)

Empirical treatment

1.05 (.58–1.89)

1.14 (.72–1.80)

Hospital with "bacteremia program"

0.81 (.52–1.25)

Hospital with "bacteremia program"

1.05 (.71–1.54)

Intervention period

Intervention period

0.46 (.29–0.72)

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA,

0.75 (.42–1.08)

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible

Staphylococcus aureus; RR, relative risk.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA,methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible

Staphylococcus aureus; RR, relative risk.

all the key aspects to consider for the management of patientswith SAB in a convenient and timely manner.

control for the effect of source, this variable was included in the

The intervention was also associated with lower mortality.

multivariate models both as a polychotomous (all the sources)

The crude association found might be influenced by the different

and as a dichotomous variable (low- and high-risk sources); the

proportion of some variables potentially affecting outcome

results were similar and showed that mortality was lower during

(confounders), such as the source of SAB. In relation with the

the intervention period. However, it is possible that it was not the

source of bacteremia, catheter-related SAB was more frequent

specific way that intervention was performed that caused the

in the intervention period; catheter-related bacteremia is

reduction in mortality; unmeasured aspects of improved man-

usually associated with lower mortality, whereas others such as

agement of the patients may have also had an impact on these

respiratory tract infections have a higher mortality rate To

results. Whatever the reason, implementing the intervention

Evidence-Based Bundle on SAB • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • 1231

Multivariate Analyses of Variables Associated With

14- and 30-Day Mortality Among Patients With Staphylococcus

Other REIPI/SAB group authors.

Carmen Velasco and Francisco

aureus Bacteremia

Javier Caballero (Departamento de Microbiología, Universidad de Sevilla);Miguel Montejo and Jorge Calvo (Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas,

Hospital de Cruces, Baracaldo); Marta Aller-Fernández (Unidad de Enfer-medades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Univer-

sidad de Cantabria); Luis Martínez, María Dolores Rojo, and Victoria

2.97 (1.51–5.87)

Manzano-Gamero (Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología,

3.04 (1.74–5.33)

Hospital Virgen de Valme, Sevilla).

High-risk sourcea

2.80 (1.32–5.92)

J. R.-B. and L. E. L.-C. had full access to all of

the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and

the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: J. R.-B., J. G.-A.,

A. P., M. A. M., and L. E. L.- C. Intervention activities: J. G.-A., M. D. dT.,

3.48 (1.89–6.41)

M. A. M., J. R.-B., E. B. B., M. C. F., M. S.-F., C. N., J. E. C., J. M. L., J. P.,

2.34 (1.40–3.92)

A. dA., M. P. M., A. R., M. M., J. C., M. A.-F., L. M. Process and interpreta-

High-risk sourcea

3.11 (1.54–6.26)

tion of microbiological isolates: C. V., F. J. C., M. dC., M. D. R., V. M.-G.

Analysis and interpretation of data: J. R.-B., M. D. dT., M. dC., and L. E. L.-

C. Drafting of the manuscript: L. E. L.-C. Critical revision of the manuscript

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

for important intellectual content: J. G.-A., M. D. dT., C. V., M. dC.,

aHigh-risk source includes endovascular sources different than catheter,

M. A. M., and A. P. Statistical analysis: L. E. L.-C. and J. R.-B. Study supervi-

endocarditis, nervous central system infections, intra-abdominal infections,

sion: J. R.-B.

and respiratory tract infection.

Financial support.

This study was supported by the Ministerio de

Economía y Competitividad, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-financed bythe European Development Regional Fund "A Way to Achieve Europe"; theSpanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/

had a positive impact. As in all bundle interventions, it is diffi-

0015); the Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía (PI-0185–2010); and the

Fundación Progreso y Salud, Junta de Andalucía.

cult to identify the impact of individual measures; we hypothe-

The funding institutions had no role in the design, perfor-

size that all or several measures act synergistically, although

mance of the study, analysis, writing, or decision to publish.

more studies would be needed to identify the essential compo-

Potential conflicts of interest. J. R.-B. has served as consultant and

nents of the intervention.

speaker for Pfizer, Roche, Astellas, Novartis, and Merck. A. P. has been aconsultant for Pfizer; has served as speaker for Wyeth, and Pfizer; and has

Some of the limitations of previous studies include their retro-

received research support from Pfizer, Wyeth, and Novartis. All other

spective nature [; that the way the recommendations were

authors report no potential conflicts.

provided were not structured or were unspecified

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential

Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the

and that they were performed in one center.

content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Our study has limitations that should be taken into account.

It has the inherent limitations of quasi-experimental, before–after designs Although our methodology tried to

control for potential confounding factors by using multivariate

1. Biedenbach DJ, Moet GJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and antimicrobial re-

analysis, it is possible that other unmeasured factors influenced

sistance pattern comparisons among bloodstream infection isolates

the results. The strengths of our study include its multicenter

from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2002).

and prospective design, the use of evidence-based indicators

Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2004; 50:59–69.

2. Fowler VG Jr, Olsen MK, Corey GR, et al. Clinical identifiers of compli-

and a structured intervention that can easily be replicated and

cated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch Intern Med 2003;

incorporated into clinical practice, and the control for the effect

of confounders.

3. Lesens O, Methlin C, Hansmann Y, et al. Role of comorbidity in mor-

tality related to Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a prospective study

In conclusion, our results suggest that it is possible to improve

using the Charlson weighted index of comorbidity. Infect Control

the clinical management and outcome of SAB by providing spe-

Hosp Epidemiol 2003; 24:890–6.

cialized, structured recommendations aimed at improving adher-

4. Lesens O, Hansmann Y, Brannigan E, et al. Positive surveillance blood

culture is a predictive factor for secondary metastatic infection in patients

ence to evidence-based QCIs.

with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Infect 2004; 48:245–52.

5. Wyllie DH, Crook DW, Peto TE. Mortality after Staphylococcus aureus

bacteraemia in two hospitals in Oxfordshire, 1997–2003: cohort study.

Supplementary Data

BMJ 2006; 333:281.

6. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, et al. Clinical practice guide-

are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online

lines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of

). Supplementary materials consist of data

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and

provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted

children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:285–92.

materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the

7. Gudiol F, Aguado JM, Pascual A, et al. Consensus document for the

sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors

treatment of bacteremia and endocarditis caused by methicillin-

should be addressed to the author.

resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sociedad Española de Enfermedades

1232 • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • López-Cortés et al

Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin

24. Fowler VG, Justice A, Moore C, et al. Risk factors for hematogenous

2009; 27:105–15.

complications of intravascular catheter–associated Staphylococcus

8. Rodríguez-Baño J, de Cueto M, Retamar P, et al. Current management

aureus bacteremia. Clin Infec Dis 2005; 40:695–703.

of bloodstream infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010; 8:815–29.

25. Chang CF, Kuo BI, Chen TL, et al. Infective endocarditis in mainte-

9. Fowler VG Jr, Sanders L, Sexton D, et al. Outcome of Staphylococcus

nance hemodialysis patients: fifteen years' experience in one medical

aureus bacteremia according to compliance with recommendations of

center. J Nephrol 2004; 17:228–35.

infectious diseases specialists: experience with 244 patients. Clin Infect

26. Reed SD, Friedman JY, Engemann JJ, et al. Costs and outcomes among

Dis 1998; 27:478–86.

hemodialysis-dependent patients with methicillin-resistant or methicil-

10. Jenkins TC, Price CS, Sabel AL, et al. Impact of routine infectious diseas-

lin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp

es service consultation on the evaluation, management, and outcomes of

Epidemiol 2005; 26:175–83.

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:1000–8.

27. Ringberg H, Thoren A, Lilja B. Metastatic complications of Staph-

11. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, et al. Infectious diseases consultation lowers

ylococcus aureus septicemia: to seek is to find. Infection 2000; 28:

mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore)

2009; 88:263–7.

28. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke cri-

12. Rieg S, Peyerl-Hoffmann G, de With K, et al. Mortality of Staphylococ-

teria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000;

cus aureus bacteremia and infectious diseases specialist consultation: a

study of 521 patients in Germany. J Infect 2009; 59:232–9.

29. Hartstein AI, Mulligan ME, Morthland VH, et al. Recurrent Staphylo-

13. Honda H, Krauss M, Jones J, et al. The value of infectious diseases con-

coccus aureus bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 1992; 30:670–4.

sultation in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Med 2010;

30. Loza Fernández de Bobadilla E, Planes Reig A, Rodríguez-Creixems M.

Hemocultivos. In: Procedimientos en Microbiología Clínica. Sociedad

14. Nagao M, Iinuma Y, Saito T, et al. Close cooperation between infectious

Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, 2003.

disease physicians and attending physicians can result in better man-

agement and outcome for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacterae-

Accessed 14 March 2013.

mia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010; 16:1783–8.

31. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for

15. Robinson JO, Pozzi-Langhi S, Phillips M, et al. Formal infectious dis-

antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In: 20th informational supplement,

eases consultation is associated with decreased mortality in Staphylo-

June 2010. Update M100-S20-U. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2010.

coccus aureus bacteraemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;

32. Minton J, Clayton J, Sandoe J, et al. Improving early management of

bloodstream infection: a quality improvement project. BMJ 2008;

16. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al.; ACCP/SCCM Consensus Confer-

ence Committee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines

33. Byl B, Clevenbergh P, Jacobs F, et al. Impact of infectious diseases spe-

for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consen-

cialists and microbiological data on the appropriateness of antimicrobi-

sus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/

al therapy for bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29:60–6.

Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest 2009; 136:e28.

34. Mainz J. Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the

17. Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE, et al. A prospective multicenter

art methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15:i5–11.

study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis,

35. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality im-

risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicillin resistance.

provement. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15:523–30.

Medicine (Baltimore) 2003; 82:322–32.

36. Retamar P, Portillo MM, López-Prieto MD, et al. Impact of inadequate

18. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying

empirical therapy on the mortality of patients with bloodstream infec-

prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and vali-

tions: a propensity score-based analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother

dation. J Chron Dis 1987; 40:373–83.

2012; 56:472–8.

19. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, et al. Health-care associated blood-

37. Bouza E, Sousa D, Muñoz P, et al. Bloodstream infections: a trial of the

stream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition

impact of different methods of reporting positive blood culture results.

of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:791–7.

Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1161–9.

20. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. CDC definitions for nosocomial

38. Harris AD, Bradham DD, Baumgarten M, et al. The use and interpreta-

infections. Am J Infect Control 1998; 16:128–40.

tion of quasiexperimental studies in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis

21. Lodise TP, McKinnon PS, Swiderski L, et al. Outcomes analysis of

2004; 38:1586–91.

delayed antibiotic treatment for hospital-acquired Staphylococcus

39. Dryden M, Andrasevic AT, Bassetti M, et al. A European survey of anti-

aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:1418–23.

biotic management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infec-

22. Soriano A, Marco F, Martínez JA, et al. Influence of vancomycin mini-

tion: current clinical opinion and practice. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;

mum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infec Dis 2008; 46:193–200.

40. Shardell M, Harris AD, El-Kamary SS, et al. Statistical analysis and ap-

23. Mitchell DH, Howden BP. Diagnosis and management of Staphylococ-

plication of quasi experiments to antimicrobial resistance intervention

cus aureus bacteraemia. Intern Med J 2005; 35:S17–24.

studies. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:901–7.

Evidence-Based Bundle on SAB • CID 2013:57 (1 November) • 1233

Figure S1. Form used to provide recommendations during the intervention

period (English translation). The form was adapted at each participating center

for electronic or paper charts.

S References.

1. Biedenbach DJ, Moet GJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and antimicrobial

resistance pattern comparisons among bloodstream infection isolates

from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveil ance Program (1997–2002).

Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2004; 50:59–69.

2. Fowler VG Jr, Olsen MK, Corey GR, et al. Clinical identifiers of

complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch Intern Med, 2003;

3. Lesens O, Methlin C, Hansmann Y, et al. Role of comorbidity in mortality

related to Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a prospective study using

the Charlson weighted index of comorbidity. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol, 2003; 24:890-896.

4. Lesens O, Hansmann Y, Brannigan E, et al. Positive surveil ance blood

culture is a predictive factor for secondary metastatic infection in patients

with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Infect, 2004; 48:245-252.

5. Wyl ie DH, Crook DW, Peto TE. Mortality after Staphylococcus aureus

bacteraemia in two hospitals in Oxfordshire, 1997-2003: cohort study.

BMJ, 2006; 333:281.

6. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, et al. Clinical practice

guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the

treatment of methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in

adults and children. Clin Infect Dis, 2011; 52:285-292.

7. Gudiol F, Aguado JM, Pascual A, et al. Consensus document for the

treatment of bacteremia and endocarditis caused by methicil in-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus. Sociedad Española de Enfermedades

Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin, 2009;

8. Rodríguez-Baño J, de Cueto M, Retamar P, et al. Current management

of bloodstream infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2010; 8: 815-829.

9. Fowler VG Jr, Sanders L, Sexton D, et al. Outcome of Staphylococcus

aureus bacteremia according to compliance with recommendations of

infectious diseases specialists: experience with 244 patients. Clin Infect

Dis, 1998; 27:478–486.

10. Jenkins TC, Price CS, Sabel AL, et al. Impact of routine infectious

diseases service consultation on the evaluation, management, and

outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2008;

11. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, et al. Infectious Diseases consultation lowers

mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore)

2009; 88:263-267.

12. Rieg S, Peyerl-Hoffmann G, de With K, et al. Mortality of Staphylococcus

aureus bacteremia and infectious diseases specialist consultation: a

study of 521 patients in Germany. J Infect, 2009; 59:232-239.

13. Honda H, Krauss M, Jones J, et al. The value of infectious diseases

consultation in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Med, 2010;123:

14. Nagao M, Iinuma Y, Saito T, et al. Close cooperation between infectious

disease physicians and attending physicians can result in better

management and outcome for patients with Staphylococcus aureus

bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2010; 16:1783-1788.

15. Robinson JO, Pozzi-Langhi S, Phil ips M, et al. Formal infectious

diseases consultation is associated with decreased mortality in

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis,

2012; 31:2421-2428.

16. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al; ACCP/SCCM Consensus

Conference Committee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and

guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The

ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American Col ege of

Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest, 2009;

17. Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE, et al. A prospective multicenter

study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis,

risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicil in resistance.

Medicine (Baltimore), 2003; 82:322-32.

18. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying

prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and

validation. J Chron Dis, 1987; 40:373-383.

19. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, et al. Health-care associated

bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted

definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med, 2002;

20. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. CDC definitions for nosocomial

infections. Am J Infect Control, 1998; 16:128-140.

21. Lodise TP, McKinnon PS, Swiderski L, et al. Outcomes analysis of

delayed antibiotic treatment for hospital-acquired Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2003; 36:1418–1423.

22. Soriano A, Marco F, Martínez JA, et al. Influence of vancomycin

minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicil in-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infec Dis, 2008; 46:193–200.

23. Mitchel DH, Howden BP. Diagnosis and management of Staphylococcus

aureus bacteraemia. Intern Med J, 2005; 35:S17-24.

24. Fowler VG, Justice A, Moore C, et al. Risk factors for hematogenous

complications of intravascular catheter–associated Staphylococcus

aureus bacteremia. Clin Infec Dis, 2005; 40:695–703.

25. Chang CF, Kuo BI, Chen TL, et al. Infective endocarditis in maintenance

hemodialysis patients: fifteen years' experience in one medical center. J

Nephrol, 2004; 17:228-235.

26. Reed SD, Friedman JY, Engemann JJ, et al. Costs and outcomes among

hemodialysis-dependent patients with methicil in-resistant or methicil in-

susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol, 2005; 26:175-183.

27. Ringberg H, Thoren A, Lilja B. Metastatic complications of

Staphylococcus aureus septicemia: to seek is to find. Infection, 2000;

28. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke

criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis, 2000;

29. Hartstein AI, Mul igan ME, Morthland VH, et al. Recurrent

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol, 1992; 30:670-674.

30. Loza Fernández de Bobadil a E. Planes Reig A, Rodríguez-Creixems M.

Hemocultivos. In: Procedimientos en Microbiología Clínica. Sociedad

Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, 2003.

Available at: http://www.seimc.org/documentos/protocolos/microbiologia.

31. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. Performance Standards for

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twentieth informational supplement

June 2010. Update M100-S20-U. Clinical and laboratory standard

institute, Wayne, PA 2010.

32. Minton J, Clayton J, Sandoe J, et al. Improving early management of

bloodstream infection: a quality improvement project. BMJ, 2008;

33. Byl B, Clevenbergh P, Jacobs F, et al. Impact of infectious diseases

specialists and microbiological data on the appropriateness of

antimicrobial therapy for bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 1999; 29:60-66.

34. Mainz J. Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the art

methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care, 2003; 15:i5-11.

35. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality

improvement. Int J Qual Health Care, 2003; 15:523-530.

36. Retamar P, Portil o MM, López-Prieto MD, et al. Impact of inadequate

empirical therapy on the mortality of patients with bloodstream infections:

a propensity score-based analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012;

37. Bouza E, Sousa D, Muñoz P, et al. Bloodstream infections: a trial of the

impact of different methods of reporting positive blood culture results.

Clin Infect Dis, 2004; 39:1161-9.

38. Harris AD, Bradham DD, Baumgarten M, et al. The use and

interpretation of quasiexperimental studies in infectious diseases. Clin

Infect Dis, 2004; 38:1586-1591.

39. Dryden M, Andrasevic AT, Bassetti M, et al. A European survey of

antibiotic management of methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

infection: current clinical opinion and practice. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2010;

40. Shardel M, Harris AD, El-Kamary SS, et al. Statistical analysis and

application of quasi experiments to antimicrobial resistance intervention

studies. Clin Infect Dis, 2007; 45: 901-907.

41. Schweizer ML, Furuno JP, Harris AD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of

nafcil in or cefazolin versus vancomycin in methicillin-susceptible

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis, 2011; 11:279.

42. Lee S, Choe PG, Song KH, et al. Is cefazolin inferior to nafcil in for

treatment of methicil in-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia?

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011; 55:5122-5126.

43. Li Y, Friedman JY, O'Neal BF, et al. Outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus

infection in hemodialysis-dependent patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol,

2009; 4:428-434.

44. Crowley AL, Peterson GE, Benjamin DK Jr, et al. Venous thrombosis in

patients with short- and long-term central venous catheter-associated

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:385-390.

45. Kim SH, Kim KH, Kim HB, et al. Outcome of vancomycin treatment in

patients with methicil in-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2008; 52:192-197.

46. Reed SD, Friedman JY, Engemann JJ, et al. Costs and outcomes among

hemodialysis-dependent patients with methicil in-resistant or methicil in-

susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol, 2005; 26:175-183.

47. Lesens O, Hansmann Y, Brannigan E, et al. Positive surveil ance blood

culture is a predictive factor for secondary metastatic infection in patients

with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Infect, 2004; 48:245-252.

48. Fätkenheuer G, Preuss M, Salzberger B, et al. Long-term outcome and

quality of care of patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Eur J

Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2004; 23:157-162.

49. Osmon S, Ward S, Fraser VJ, et al. Hospital mortality for patients with

bacteremia due to Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Chest, 2004; 125:607-616.

50. Johnson LB, Almoujahed MO, Ilg K, et al. Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: compliance with standard treatment, long-term outcome and

predictors of relapse. Scand J Infect Dis, 2003; 35:782-789.

51. Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, et al. Outcome of Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia in patients with eradicable foci versus noneradicable foci.

Clin Infect Dis, 2003; 37:794-799.

52. Lodise TP, McKinnon PS, Swiderski L, et al. Outcomes analysis of

delayed antibiotic treatment for hospital-acquired Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2003; 36:1418-1423.

53. Austin TW, Austin MA, Coleman B. Methicil in-resistant/methicil in-

sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Saudi Med J, 2003;

54. de Oliveira Conterno L, Wey SB, Castelo A. Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: comparison of two periods and a predictive model of

mortality. Braz J Infect Dis, 2002; 6:288-297.

55. Lentino JR, Baddour LM, Wray M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and

other bacteremias in hemodialysis patients: antibiotic therapy and

surgical removal of access site. Infection, 2000; 28:355-360.

56. Gopal AK, Fowler VG Jr, Shah M, et al. Prospective analysis of

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in nonneutropenic adults with

malignancy. J Clin Oncol, 2000; 18:1110-1115.

57. Lundberg J, Nettleman MD, Costigan M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: the cost-effectiveness of long-term therapy associated with

infectious diseases consultation. Clin Perform Qual Health Care, 1998;

58. Hil PC, Birch M, Chambers S, et al. Prospective study of 424 cases of

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: determination of factors affecting

incidence and mortality. Intern Med J, 2001; 31:97-103.

59. Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE Jr, et al. A prospective

multicenter study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of

endocarditis, risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicil in

resistance. Medicine (Baltimore), 2003; 82:322-332.

60. Wang JT, Wang JL, Fang CT, et al. Risk factors for mortality of

nosocomial methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

bloodstream infection: with investigation of the potential role of

community-associated MRSA strains. J Infect, 2010; 61:449-457.

61. Lin SH, Liao WH, Lai CC, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with

persistent methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in a

tertiary care hospital in Taiwan. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2010; 65:1792-

62. Walraven CJ, North MS, Marr-Lyon L, Deming P, et al. Site of infection

rather than vancomycin MIC predicts vancomycin treatment failure in

methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob

Chemother, 2011; 66:2386-2392.

63. Stryjewski ME, Szczech LA, Benjamin DK Jr, et al. Use of vancomycin or

first-generation cephalosporins for the treatment of hemodialysis-

dependent patients with methicil in-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2007; 44:190-196.

64. Hetem DJ, de Ruiter SC, Buiting AG, et al. Preventing Staphylococcus

aureus bacteremia and sepsis in patients with Staphylococcus aureus

colonization of intravascular catheters: a retrospective multicenter study

and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 2011; 90:284-288.

65. Fitzgibbons LN, Puls DL, Mackay K, Forrest GN. Management of gram-

positive coccal bacteremia and hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis, 2011;

66. Naber CK. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: epidemiology,

pathophysiology, and management strategies. Clin Infect Dis, 2009;

67. Cosgrove SE, Fowler VG Jr. Management of methicil in-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2008; 46:S386-93.

68. Hil EE, Vanderschueren S, Verhaegen J, et al. Risk factors for infective

endocarditis and outcome of patients with Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia. Mayo Clin Proc, 2007; 82:1165-1169.

69. Hawkins C, Huang J, Jin N, et al. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: an analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med,

2007; 167:1861-1867.

70. Thwaites GE, Edgeworth JD, Gkrania-Klotsas E, et al. Clinical

management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Lancet Infect Dis,

2011; 11:208-222.

71. Pigrau C, Rodríguez D, Planes AM, et al. Management of catheter

related Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: when may sonographic study

be unnecessary? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2003; 22: 713-719.

72. Van Hal SJ, Marthur G, Kel y J, et al. The role of thansthoracic

ecocardiography in excluding left sided infective endocarditis in

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Hosp Infec, 2005; 51:218-221.

73. Kaasch AJ, Fowler VG Jr, Rieg S, et al. Use of a simple criteria set for

guiding echocardiography in nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis, 2011; 53:1-9.

74. Chang FY, Peacock JE Jr, Musher DM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: recurrence and the impact of antibiotic treatment in a

prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore), 2003; 82:333–339.

75. Joseph JP, Meddows TR, Webster DP, et al. Prioritizing

echocardiography in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob

Chemother. 2013; 68:444-9.

76. Lodise TP, Graves J, Graffunder E, et al. Relationship between

vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicil in-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother, 2008; 52:3315-3320.

77. Hidayat LK, Hsu DI, Quist R, et al. High-dose vancomycin therapy for

methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: efficacy and

toxicity. Arch Intern Med, 2006; 166:2138-44.

78. Corey GR, Stryjewski ME, Everts RJ. Short-course therapy for

bloodstream infections in immunocompetent adults. Int J Antimicrob

Agents, 2009; 34:S47-51.

79. González C, Rubio M, Romero-Vivas J, et al. Bacteremic pneumonia due

to Staphylococcus aureus: A comparison of disease caused by

methicil in-resistant and methicil in-susceptible organisms. Clin Infect Dis.

1999; 29:1171-7.

80. Kul ar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, et al. Impact of vancomycin exposure on

outcomes in patients with methicil in-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

bacteremia: support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin

Infect Dis. 2011; 52:975-81.

81. Nissen JL, Skov R, Knudsen JD, et al. Effectiveness of penicil in,

dicloxacil in and cefuroxime for penicil in-susceptible Staphylococcus

aureus bacteraemia: a retrospective, propensity-score-adjusted case-

control and cohort analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013. In press.

Table S1. Summary of adherence fo the 6 quality-of-care indicators used in this study as found in previous reports evaluating the

impact of infectious disease specialist consultation on the management of S. aureus bacteraemia. Data are expressed as

percentage of patients in the intervention / non-intervention groups except where specified.

Prospective cohort /

Routine IDCa Before-after /

Retrospective cohort /

Prospective cohort /

Retrospective cohort /

Retrospective cohort /

Before-after, multicenter /

MRSA: methicil in-resistant S. aureus. IDC: Infectious diseases consultation.

aData means adherence / non adherence to infectious diseases recommendations. bTransesophageal echocardiography

Source: http://www.ateams.nl/sites/default/files/Bundle%20Intervention%20Staphylococcus%20aureus%20Bacteremia%20Clin%20Infect%20Dis%202013.pdf

Back to the Training Manual International Clinical Recommendations onScar Management Thomas A. Mustoe, M.D., Rodney D. Cooter, M.D., Michael H. Gold, M.D., F. D. Richard Hobbs,F.R.C.G.P., Albert-Adrien Ramelet, M.D., Peter G. Shakespeare, M.D., Maurizio Stella, M.D.,Luc Téot, M.D., Fiona M. Wood, M.D., and Ulrich E. Ziegler, M.D., for the International Advisory Panelon Scar Management

Intellectual Property and Human Development Trends and scenarios in the legal protection of traditional knowledge Charles McManis and Yolanda Terán1 Introduction This chapter discusses the currently much debated issue of traditional knowledge (TK) protection. Opinions differ widely, not only as to how TK should be protected, but even as to whether TK should be protected at all. It is commonly accepted that intellectual property rights (IPRs) in their current form are ill-suited for this category of knowledge. But does it follow that TK should be placed or left in the public domain for anybody to use as they wish? For many indigenous peoples, traditional communities and developing country governments, this seems neither fair nor reasonable. In response, they have insisted that this issue be discussed at the highest level in such forums as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Conference of the Parties (COP), and also be addressed at the national and regional levels. Proposals have included reforms to current IP regimes in order to prevent misappropriation of TK and the development of sui generis systems that vest rights in TK holders and TK-producing communities. However, considerable conceptual and political difficulties remain, and these remaining difficulties make it hard to predict the future of TK, as a legal and diplomatic issue.