Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Atomoxetine hydrochloride in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder: a placebo-controlled italian study

European Neuropsychopharmacology (2009) 19, 822–834

Atomoxetine hydrochloride in the treatmentof children and adolescents withattention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbidoppositional defiant disorder: A placebo-controlledItalian study

Grazia Dell'Agnello a, Dino Maschietto b, Carmela Bravaccio c,Filippo Calamoneri d, Gabriele Masi e, Paolo Curatolo f, Dante Besana g,Francesca Mancini a, Andrea Rossi a, Lynne Poole h,Rodrigo Escobar i, Alessandro Zuddas j,⁎for the LYCY Study Group

a Medical Department, Eli Lilly Italia, Italyb Operative Unit of Child Neuropsychiatry, Azienda USL n 10 Veneto Orientale, San Donà di Piave, Venezia, Italyc Department of Pediatrics, University of Naples "Federico II", Italyd Clinic of Child Neuropsychiatry, University Policlinic of Messina, Italye Department of Child Neuropsychiatry, IRCCS Fondazione Stella Maris, Calambrone, Pisa, Italyf Department of Child Neuropsychiatry, Tor Vergata University of Rome, Italyg Operative Structure of Child Neuropsychiatry, Hospital of Alessandria, Italyh Eli Lilly and Co. UKi European Medical Department, Eli Lilly and Co. Alcobendas, Madrid, Spainj Department of Neuroscience, Section of Child Neuropsychiatry, University of Cagliari, Italy

Received 3 January 2009; received in revised form 2 July 2009; accepted 23 July 2009

Objective: The primary aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of atomoxetine in improving

hyperactivity disorder;

ADHD and ODD symptoms in paediatric patients with ADHD and comorbid oppositional defiant

Oppositional defiant

disorder (ODD), non-responders to previous psychological intervention with parent support.

Methods: This was a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial conducted in patientsaged 6–15 years, with ADHD and ODD diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria by a structured

⁎ Corresponding author. Centre for Pharmacological Therapies in Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry, Department of Neuroscience,

University of Cagliari, via Ospedale, 46, 09124 Cagliari, Italy. Tel.: +39 070 609 3509/3510; fax: +39 070 669591.

E-mail address: (A. Zuddas).

0924-977X/$ - see front matter 2009 Elsevier B.V. and ECNP. All rights reserved.

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

clinical interview (K-SADS-PL). Only subjects who are non-responders to a 6-week standardizedparent training were randomised to atomoxetine (up to 1.2 mg/kg/day) or placebo (in a 3:1 ratio)for the following 8-week double blind phase. Results: Only 2 of the 156 patients enrolled for theparent support phase (92.9% of males; mean age: 9.9 years), improved after the parent trainingprogram; 139 patients were randomised for entering in the study and 137 were eligible for efficacyanalysis. At the end of the randomised double blind phase, the mean changes in the Swanson,Nolan and Pelham Rating Scale-Revised (SNAP-IV) ADHD subscale were −8.1 ± 9.2 and −2.0 ± 4.7,respectively in the atomoxetine and in the placebo group (p b 0.001 between groups); changes inthe ODD subscale were −2.7 ± 4.1 and −0.3 ± 2.6, respectively in the two groups (p = 0.001 betweengroups). The CGI-ADHD-S score decreased in the atomoxetine group (median change at endpoint:−1.0) compared to no changes in the placebo group (pb0.001 between groups). Statisticallysignificant differences between groups, in favour of atomoxetine, were found in the CHIP-CEscores for risk avoidance domain, emotional comfort and individual risk avoidance subdomains.

An improvement in all the subscales of Conners Parents (CPRS-R:S) and Teacher (CTRS-R:S)subscales was observed with atomoxetine, except in the cognitive problems subscale in the CTRS-R:S. Only 3 patients treated with atomoxetine discontinued the study due to adverse events. Noclinically significant changes of body weight, height and vital signs were observed in both groups.

Conclusions: Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD, whodid not initially respond to parental support, was associated with improvements in symptoms ofADHD and ODD, and general health status. Atomoxetine was well tolerated.

2009 Elsevier B.V. and ECNP. All rights reserved.

Longitudinal data suggest that ADHD predicts academicoccupational dysfunction, earlier sexual intercourse, and

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is charac-

early parenthood (

terised by a persistent high level of hyperactive, inattentive

), whereas the presence of ODD may modulate persistence

and impulsive behaviour, which can be prevalent in both child

of associated disorders ) and may

and adolescent populations. Although information on preva-

predispose affected children to the subsequent development

lence and incidence of ADHD in Europe is scarce and depending

conduct disorders, delinquent behaviour and substance misuse

on the used definition, a range from 2 to 5% (for subjects

aged 6–16 years) has been reported in most of studies based on

the ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, respectively

Clinical studies evaluating the effects of stimulants in

(A few different epidemiological studies

treating children with ADHD and comorbid ODD reported

conducted in Italy estimated a frequency of ADHD in the

inconclusive results. Some of these studies that investigate

paediatric population ranging from 4% to 7%

children with mental retardation, were conducted either

in laboratory conditions or very specific settings such as

gender ratio of 7:1 between males and females, aligned with

partial hospitalization programs or strictly academic situa-

data from international literature

). Factor analysis of ADHD and

), so that the generalization

oppositional defiant symptoms reports by both Italian parents

of their findings does not necessarily extend to the home

and teachers indicate a structure similar to that observed in

environment or more natural conditions. Others, without

the US and Northern Europe ).

specifically assessing oppositional-defiant symptoms,

ADHD may be associated with additional psychiatric

reported the efficacy of methylphenidate for CD symptoms

disorders such as mood and anxiety disorders and disruptive

in ADHD patients with comorbid CD, also indicating that

behaviour disorders. In particular, oppositional defiant disor-

the presence of a diagnosis of ODD or CD diminished the

der (ODD) is among the most common comorbid psychiatric

effect size of the drug

disorders in patients with ADHD, occurring in up to 67% of

). The Multicenter Treatment

clinically referred populations () and

Study of Children with ADHD (MTA study) showed that the

representing a serious clinical problem. ODD is characterized

presence of ODD did not alter the expected pattern of ADHD

by a pattern of developmentally inappropriate negativistic,

symptom response and suggested that ODD symptoms may

hostile and defiant behaviour causing clinically significant

show greater improvement with pharmacological treatment

impairment in social, familiar or academic functioning.

than with behavioural management (

Genetic, family environment and psychometric studies indi-

cate that they have separate aetiologies and pathophysio-

Atomoxetine hydrochloride is a potent inhibitor of the

logical mechanisms

presynaptic norepinephrine transporters, and has minimal

affinity for other neurotransmitter transporters or receptors.

ADHD combined with ODD tend to have more severe ADHD

In comparative placebo-controlled studies conducted in

symptoms, more peer problems, and more family distress

children, adolescents and adults, atomoxetine consistently

compared to children with ADHD alone ().

reduced symptoms of ADHD (

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

cant laboratory or ECG abnormalities; medical conditions likely to

and positive outcomes have also been reported in family and

increase sympathetic nervous system activity or regular intake of

social functioning of children and adolescents with ADHD and

sympathomimetic drugs; narrow-angle glaucoma; uncontrolled

in their quality of life

thyroid dysfunction; likelihood of start of structured psychotherapyat any time during the study; pregnant or breastfeeding females, or

Moreover, atomoxetine seems to

females at risk of pregnancy.

exert positive effects on additional psychiatric conditions,such as other disruptive behaviour disorders, mood andanxiety disorders, which are often associated with ADHD

2.2. Study design

(An analysis of data from placebo-controlled studies in

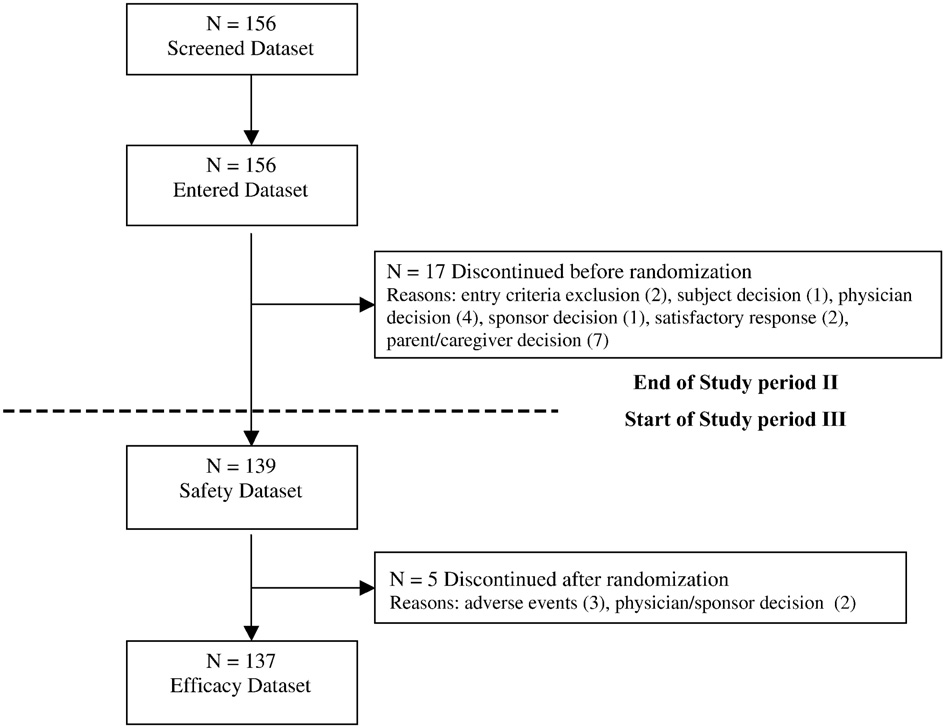

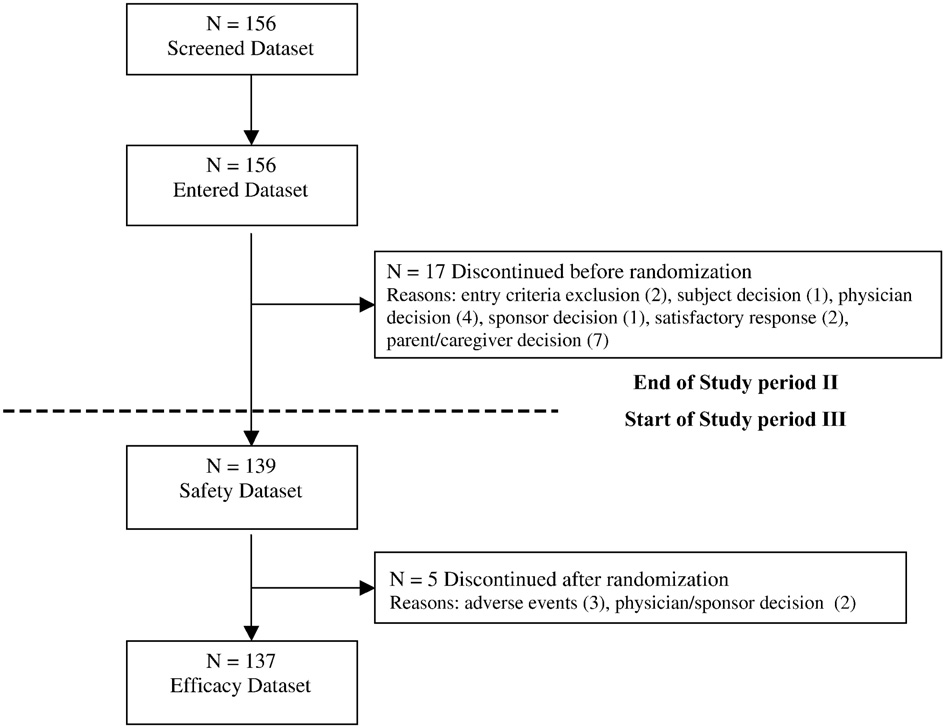

The entire study consisted of 4 study periods (

children and adolescents provided evidence on the efficacyof atomoxetine in reducing symptoms and improving social

a) Study period I (screening phase): this was a screening and

and family functioning in patients with ADHD and comorbid

assessment/evaluation period, ranging from 3 to 28 days, to

ensure eligibility for the study, and was started after parent's

ally, a recent review has shown that atomoxetine reduces

consent was obtained.

ADHD symptoms in both ODD-comorbid and non-comorbid

b) Study period II (open-label, parent support phase): during this

subjects to similar extents and that reduction in ODD

6-week phase, the investigators provided a standardized

symptoms is highly related to the magnitude of ADHD

management for the parental support. Parents received weeklyseries of advice on the management of the behavioural problems

response, indicating that the presence of ODD symptoms

of their children from qualified psychologists or child neuro-

does not affect the clinical effectiveness of atomoxetine in

psychiatrists, based on standardized procedures (

ADHD subjects Relapse of ADHD

With this program, parents were trained to provide clear,

symptoms is also not influenced by the presence of comorbid

consistent expectations, directions and limits to their children,

to use modification principles to reinforce positive behaviours

In a recent placebo-controlled study conducted in Europe

and to eliminate or reduce negative behaviours that create

and Australia on children with ADHD and comorbid ODD, no

problems for their children. Additionally, the training helped

significant differences between atomoxetine and placebo

parents to become able to assist their children in making friends

were found for ODD symptoms, although atomoxetine

and learning to work cooperatively with others. Response

significantly improved ADHD symptoms

criteria were defined as an improvement in CGI-S score of 2 ormore from baseline and at least a 30% decrease from baseline

suggesting that the social and cultural environment may

in 18 items of the ADHD subscale score of investigator-rated

play a role in modulating the atomoxetine effects on ODD

SNAP-IV. Only patients who did not reach both mentioned

criteria were randomised to the study period III.

The present study was carried out to evaluate the efficacy

c) Study period III (randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled

of atomoxetine in improving ADHD and ODD symptoms in an

phase). This was an 8-week period of double blind treatment. At

Italian population of children and adolescents initially not

the beginning of this period, patients who did not respond to the

responding to a parent training intervention, and to assess

6-week period of parent support were randomly assigned to

the extent of improvements in health status and level of

treatment with atomoxetine or placebo in a ratio of 3:1 (i.e. with

approximately 75% of patients receiving atomoxetine and 25% ofpatients receiving placebo). Patients randomised to atomoxetinewere titrated, in 7 days, from 0.5 mg/kg/day (dose ranging from

0.5 to 0.8 mg/kg/day) to the target dose of 1.2 mg/kg/day (rangefrom 1.0 to 1.4 mg/kg/day), to be administered for the first

2.1. Patient population

8 weeks of the study once daily in the morning. In case of onset offatigue or somnolence during the day, the investigator coulddecide to administer the dose in the evening.

The study group included patients of both sexes aged 6–15 years,

d) Study period IV (long-term, open-label extension phase). This was

with ADHD and ODD diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria. The

an optional, open-label, long-term extension phase for patients

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School

who had completed study period III. At the end of the 8-week

Aged Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL), a semi-

double blind period, all patients had the choice to receive open

structured diagnostic interview that includes supplements for

label atomoxetine treatment for a long-term period until the drug

affective disorders, anxiety, and behavioural disorders (including

became commercially available. During this phase information on

ADHD) was completed at screening for each subject.

efficacy, health outcomes and safety were collected.

To be eligible in the study, patients were required to have a score

of at least 1.5 SD above the age norm for the ADHD subscale of theSNAP-IV, a CGI-S ≥4 at both screening and baseline, a SNAP-IV ODD

The study periods I–III included 14 visits: visit 1 was the screening

subscale score of at least 15, and a normal intelligence, i.e. a score

visit, weekly visits were placed during the study period II (parent

of ≥70 on an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test. Patients with any of

support phase, visits 2–8) and during the initial 4 weeks of the phase

the following conditions were excluded from study participation:

III (randomised double blind phase, visits 8–12); the remaining visits

body weight b20 kg; history of bipolar I or II disorder, or history of

(13 and 14) took place every 2 weeks. As study period IV is already

psychosis or pervasive development disorder; history of any seizure

ongoing, this article refers to data measured up at the end of the

disorder (other than febrile seizures) or past/concomitant intake of

randomised double blind phase.

anticonvulsants for seizure control; serious risk of suicide; history of

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anorexics,

severe drug allergies; current or past (within 3 months) alcohol or

anticoagulant, benzodiazepines and monoamine oxidase inhibitors

drug abuse; clinically significant cardiovascular disease (including

were not permitted at any time during the study. Concomitant

hypertension) or other conditions that could be worsened by an

administration of CYP2D6 inhibitors was not permitted, and in any

increased heart rate or increased blood pressure; clinically signifi-

case they could be used only after consultation and permission of

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

Study design and study phases.

study staff physicians. Formal individual or family psychotherapy

rated instrument measures presence and severity of depression.

was excluded for the entire duration of the study.

A total score below 20 indicates an absence of depression, a scoreof 20–30 indicates borderline depression and a score of 40–60indicates moderate depression. The SCARED-Parent Version is a 41-

2.3. Outcome measures

item parent self-report questionnaire (),which measures symptoms of DSM-IV linked anxiety disorders in

Efficacy variables were measured at the start and at the end of

children, aimed at screening for panic disorder, general anxiety

period I–III. The primary efficacy measure for this study is the 18

disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, and the

items of the ADHD subscale score of the SNAP-IV. The SNAP-IV is a 26-

presence of a relevant simple phobia, and the school phobia in

item scale (0–3 score for each item) that includes 1 item for each of

clinical () and community samples (

the 18 symptoms contained in the DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD and 1

item for each of the 8 symptoms contained in the DSM-IV diagnosis of

The Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) was measured by

ODD. The SNAP-IV is a widely used measure of the symptoms of ADHD

means of the Child Health and Illness Profile-Child Edition (CHIP-CE).

and ODD. It has been validated and normalized in a sample of school-

It is a 76-item parent-rated assessment of a child's health status and

aged children from the US (

level of functioning (and examines the following

The SNAP-IV yields scores in three domains: inattention (items 1–9),

domains and sub domains: satisfaction (satisfaction with health,

hyperactivity/impulsivity (items 10–18), and oppositional (items

satisfaction with self), comfort (physical comfort, emotional

19–26). The inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and combined

comfort, limitation of activity), risk avoidance (individual risk

scores were considered as the primary efficacy measure while the

avoidance, threats to achievement, peer influences), resilience

ODD subscale score was considered a secondary measure in this

(family involvement, physical activity, social problem solving), and

achievement (academic performance, peer relations). Most of the

The CGI-S ) was used to assess the severity of the

items assess frequency of activities or feelings using a 5-point

patient's ADHD symptoms, in relation to clinician's total experience

response format.

of ADHD patients, on a 7-point scale (from 1 = normal, not ill at all, to

Adverse events were recorded at any time during the study. Body

7 = among the most extremely ill patients).

weight, height, heart rate and blood pressure were measured at

Other outcome measures of the study included the Conners'

screening and at any visit during the randomised phase.

Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CPRS-R:S) and the Conners'Teacher Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form (CTRS-R:S). The CPRS-R:S) is a 27-item rating scale completed by the parents to

2.4. Statistical analysis

assess problem behaviours related to ADHD. The CTRS-R:S is a 28-item rating scale completed by a teacher to assess

The sample size was based on the primary outcome variable, i.e. the

problem behaviours related to ADHD in the school setting. Both

18 items of the ADHD subscale score of the investigator-rated SNAP-

scales include the oppositional, cognitive problems, hyperactivity

IV. Using an estimate of the common standard deviation of 13 points,

ADHD Index subscales. In the cases of administration outside of the

a sample of 130 patients (in a 3:1 ratio atomoxetine:placebo) gave

school sessions, the CTRS-R:S had to be administered at the earliest

about 80% power to detect a difference between groups of 8 points

next time point of school-time or at the last visit prior to the school

on the SNAP-IV, that can be considered as clinically significant. The

break in the final assessment.

sample size was determined using a two-sided test with alpha = 0.05

Patients' depression and anxiety were scored by means of the

and assumed that up to 10% of patients discontinued the study

Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) and the Screen

without providing post-baseline efficacy data in the randomised

for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)-Parent

Version, respectively. The CDRS-R ()

The analysis of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints, and of

was based on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) for

vital signs, was carried out using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)

adults, but also includes questions about school. This clinician-

model on the last observation carried forward (LOCF) change from

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

Disposition of patients in the study.

baseline to endpoint, in the double blind randomised phase of the

therapy. ADHD diagnosis and anxiety/affective diagnoses at

study. The baseline score was included in the model as one of the

baseline, according with DSM IV, are summarized in .

covariates. The results of the ADHD subscale were also expressed as

The mean (± standard deviation) starting atomoxetine dose

response rate, where response was defined as at least 25%, 30% or

was 0.61 ± 0.08 mg/kg/day (range 0.44–0.80) and was titrated

40% improvement (reduction) from the start to the end of the

to 1.10 ± 0.13 mg/kg/day (range 0.85–1.33) at the end of the

randomised treatment phase of the study.

randomised phase of the study, a dose slightly below the one

Raw scores of CHIP-CE were converted in T scores based on

established standardized scores (mean of a healthy population, 50;

recommended (SPC Strattera).

standard deviation from this mean, 10) ().

Adverse events were coded using the MedDRA dictionary. Events

were considered treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE) if they

started or worsened after the first intake of study medicationcompared to the pre-baseline period. Rates of patients with TEAE in

A slight non-significant decrease in all SNAP-IV subscales scores

the double blind phase of the study were compared between groups

was observed during the parent support phase: the mean scores

using the Fisher's exact test.

at the start and at the end of this phase were, respectively, 43.3 ±6.6 and 42.1 ± 6.9 for the ADHD subscale (i.e. the 18 items ofinattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and combined domains),

A total of 156 patients (mean age: 9.9 years, 92.9% males) werescreened and entered the parent support phase. The patients'

Demographic data by treatment group at baseline.

disposition is shown in Seventeen patients discontinuedthe study during the parent support phase, before randomization

(mainly due to patient/caregiver's or Investigator's decision).

All 139 remaining patients were analysed for safety and 137

Demographic data:

for efficacy (two did not have post-baseline data). In the

atomoxetine group, 5 patients discontinued the study during

mean ± SD (range)

the double blind randomised phase. Only two patients (1.3% of

screened) responded to the parent psychological intervention

and were not randomised.

Patients' demographics are shown in No statisti-

mean ± SD (range)

cally significant differences between groups were found at

baseline (visit 8). Previous psychotherapy (of any type) was

mean ± SD (range) (110–174)

used in 18 patients (17.1%) in the atomoxetine group and in 6

(18.8%) in the placebo group, while 21 (20.0%) and 4 (12.5%)

mean ± SD (range)

patients, respectively in the two groups, used previous drug

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis and anxiety/affective

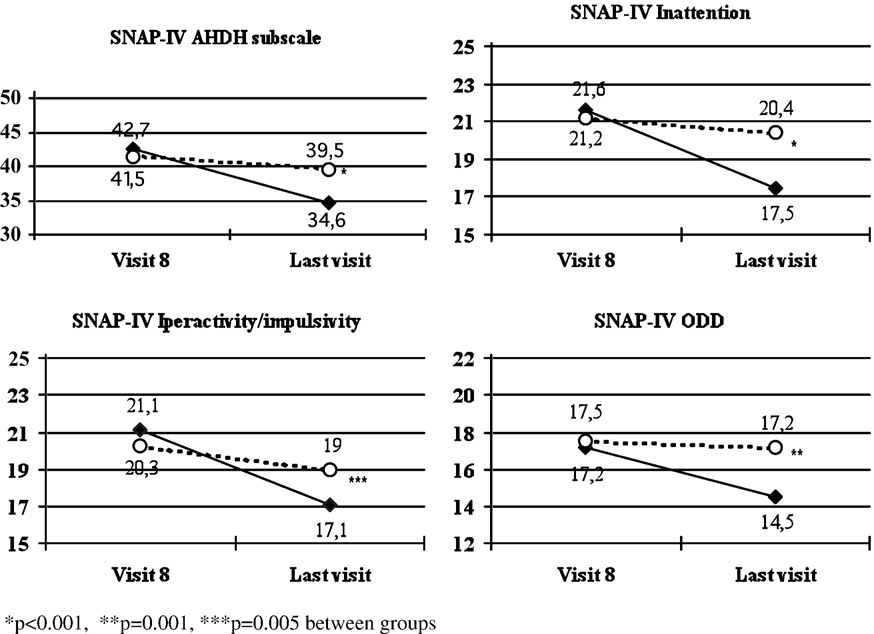

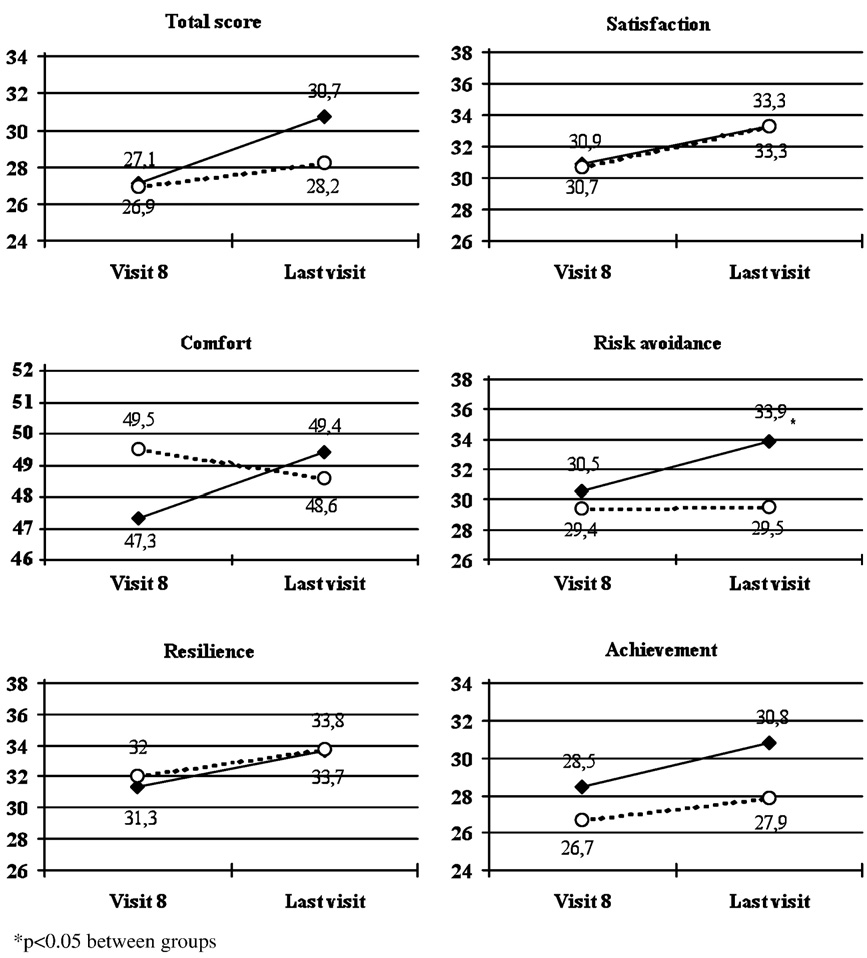

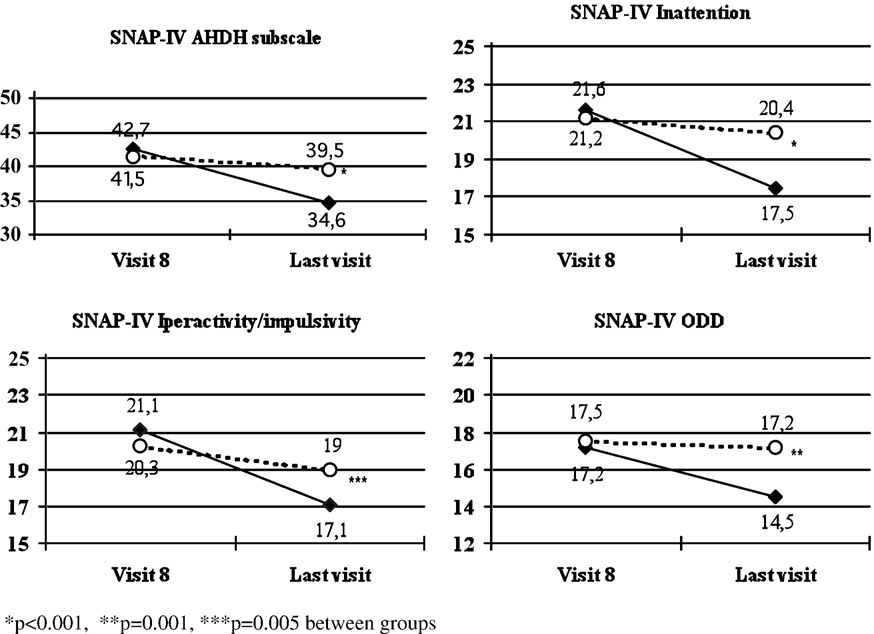

During the randomized phase, the mean changes from visit 8

diagnoses at baseline.

to the last visit in the ADHD subscale were −8.1 ± 9.2 and −2.0 ±4.7, respectively in the atomoxetine and in the placebo group

(p b 0.001 between groups). The corresponding changes in the

ODD subscale were −2.7 ± 4.1 and −0.3 ± 2.6, respectively in the

DSM-IV ADHD subtype

two groups (p = 0.001 between groups) (An analysis in

Inattentive, number (%)

response rate, defined as at least 25%, 30% or 40% improvement

Hyperactive, number (%)

(reduction) from visit 8 to the last visit in SNAP-IV ADHD

Combined, number (%)

subscale score, showed statistically significant differences

Age at onset of ADHD symptoms,

between groups, in favour of atomoxetine compared to

years, mean ± SD (range)

placebo, in 25% response (39.0% vs. 9.4%, respectively in thetwo groups, p = 0.001), in 30% response (31.4% vs. 6.3%,

Anxiety diagnoses from K-SADS:

p = 0.004) and in 40% response (18.1% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.043). A

Generalised anxiety disorders,

decrease of mean scores from visit 8 to the last visit was also

observed in any subscale for atomoxetine treated patients,

compared to no substantial changes with placebo (p b 0.001

between groups for inattention and p = 0.005 for hyperactivity/

Panic disorder, number (%)

impulsivity) ).

Separation anxiety disorder,

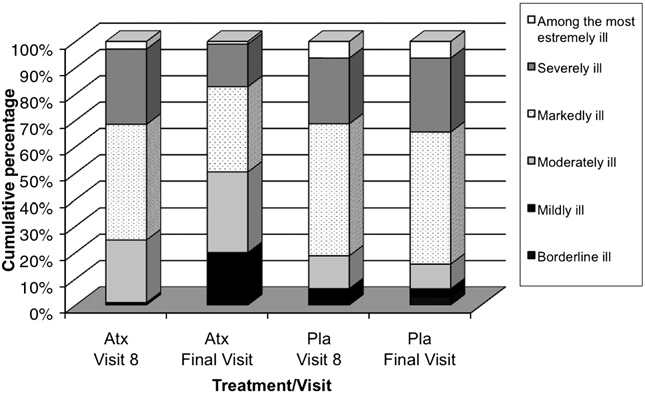

The median CGI-ADHD-S score did not change from the start to

the end (median score: 5.0 at both visits) of the parent support

Specific phobias, number (%)

phase. A statistically significant decrease in the atomoxetinegroup was observed during the randomised double-blind phase

Affective diagnoses from K-SADS:

(median change at endpoint: −1.0), compared to no changes in

Adjustment disorder, number (%)

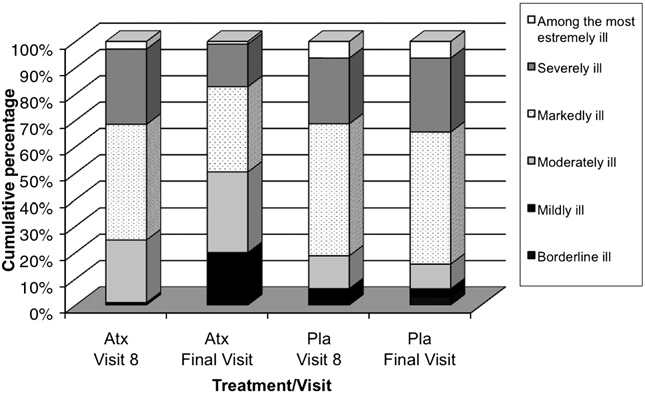

the placebo group (p b 0.001 between groups). The cumulative

Dysthymia, number (%)

distribution of CGI-ADHD-S scores shows that patients in the

Major depressive disorders,

placebo group have a similar distribution between baseline and

last visit, while almost 50% of patients treated with atomoxetine

Seasonal pattern disorders,

were moderately ill or mildly ill at last visit

The results of the CPRS-R:S and the CTRS-R:S in the parent

Any other depressive disorders,

support phase showed small decreases from baseline in all

subscales (except for unchanged mean values in the cognitiveproblems subscale in the CTRS-R:S): the mean changes in theADHD index were −1.5 in the CPRS-R:S and −1.1 in the CTRS-R:S.

The results of the CPRS-R:S and the CTRS-R:S in the randomised

21.9 ± 3.3 and 21.3 ± 3.6 for the inattention subdomain, 21.4 ± 4.2

phase are summarised in An improvement in all CPRS-R:S

and 20.8 ± 4.3 for the hyperactivity/impulsivity subdomain, and

and CTRS-R:S subscales was observed following treatment with

18.1 ± 2.5 and 17.2 ± 3.3 for the ODD subdomain.

atomoxetine, except in the cognitive problems subscale in the

Results of the SNAP-IV subscales during the randomised double blind phase (atomoxetine: full diamonds; placebo: empty

circles). Values are mean scores.

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

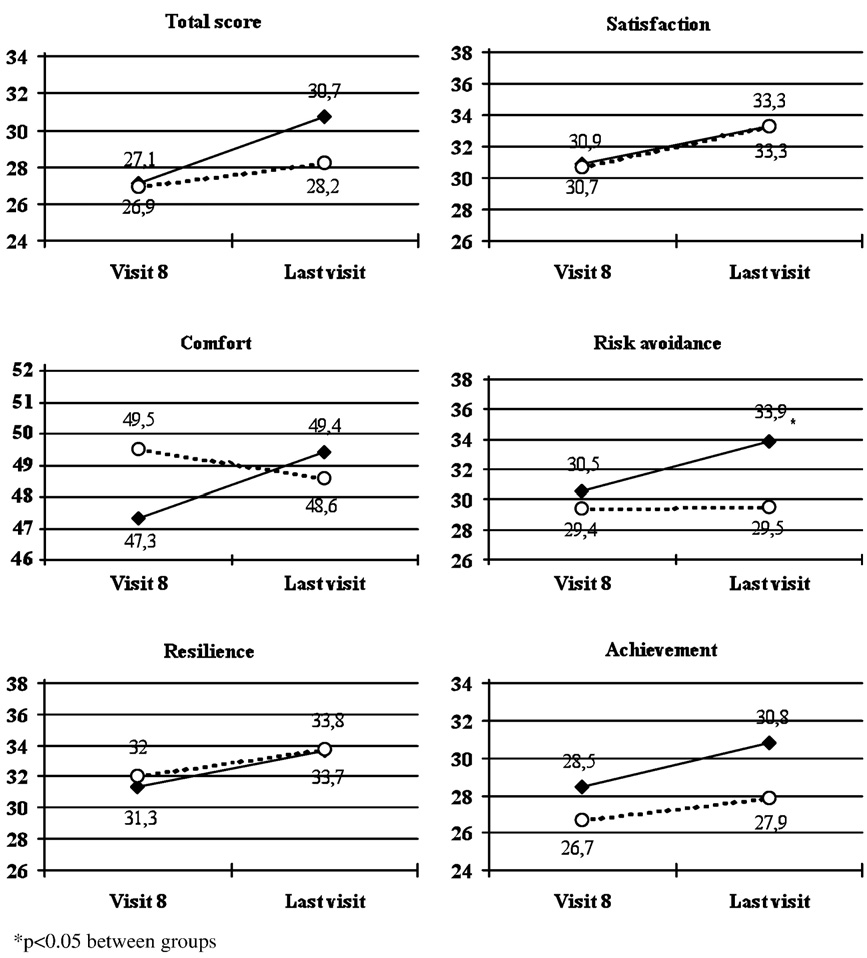

(+ 3.3) and peer relations (+ 2.1). The comparisons betweengroups showed statistically significant differences, in favour ofatomoxetine, for risk avoidance domain (p = 0.013), and foremotional comfort (p = 0.007) and individual risk avoidance(p = 0.007) subdomains.

shows the TEAEs reported in at least 5% of patients in anygroup during the randomised double blind phase of the study. Themost commonly involved system organ classes by MedDRAdictionary were gastrointestinal disorders (mainly nausea,vomiting and abdominal pain), which were reported in 45.8%

Frequency of CGI-ADHD-S score by treatment group —

of patients in the atomoxetine group and 21.9% in the placebo

study period III.

group, and metabolism and nutrition disorders (anorexia/decreased appetite), which were reported in 43.0% and 9.4% ofpatients, respectively in the two groups.

CTRS-R:S. Statistically significant differences vs. placebo were

Almost all adverse events (except in 5 cases) were of mild or

found in all subscales of the CPRS-R:S and in the oppositional

moderate severity and only 3 patients treated with atomoxetine

subscale of the CTRS-R:S, while the p value was at the limit of

discontinued the study due to adverse events. No serious

significance level in the hyperactivity subscale and in the AHDH

adverse events were reported in both groups. No substantial

index of the CTRS-R:S.

changes of mean body weight and height were observed during

The mean total scores of CDRS-R and SCARED were below the

the parent support phase, while the results in the randomised

clinical threshold at baseline and did not change in the parent

phase showed a small increase (+ 0.5 kg) of body weight with

support phase: the mean changes from baseline to the end of

placebo and a small decrease (−1.2 kg) with atomoxetine

this phase were −0.6 ± 4.1 and −0.3 ± 7.5, respectively. The

(p b 0.001), as well as mean height increased slightly more

mean changes of CDRS-R total score from visit 8 to the last visit

markedly in the placebo group (+ 1.5 cm) than in the

were −0.5 ± 4.4 in the atomoxetine group and −0.1 ± 5.0 in the

atomoxetine group (+ 1.0 cm) (p = 0.021). The mean changes in

placebo group (p = 0.870 between groups). The corresponding

vital signs from visit 8 to the end of randomised phase in the

changes of SCARED were −2.1 ± 7.6 and −1.7 ± 6.5, respectively

atomoxetine group and in the placebo group were, respectively,

in the two groups (p = 0.836 between groups).

1.0 and 5.1 mmHg in systolic blood pressure (p = 0.482), −0.2

The mean CHIP-CE total, domain and subdomain scores did

and 2.3 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.557), and 3.7

not change during the parent support phase. shows the

and 1.5 bpm in heart rate (p = 0.312). No difference was ob-

CHIP-CE total and domain T scores during the randomised

served in body temperature, between study groups at any time

double blind phase. The mean changes of CHIP-CE total score

and at endpoint.

from visit 8 to the last visit were 3.6 with atomoxetine and 1.2with placebo (p = 0.071 between groups). Improvements in meanscores of all domains were observed in the atomoxetine group.

The results of CHIP-CE subdomains in the atomoxetine groupshowed marked improvements from visit 8 to the last visit in

ADHD treatment guidelines suggest that pharmaco-therapy

satisfaction with self (mean change: + 4.2), emotional comfort

should be used as part of a multi-modal treatment package

(+ 2.1), individual risk avoidance (+ 2.7), threats to achievement

including parent training, family or school interventions

Results of the CPRS-R:S and the CTRS-R:S in the randomised double blind phase.

Cognitive problems

Cognitive problems

Values are means ± standard deviation. p values refer to comparisons between groups in changes from visit 8 to the last visit.

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

CHIP-CE total and domains scores during the randomised double blind phase (atomoxetine: full diamonds; placebo: empty

circles). Values are mean scores.

and psychotherapy. In Europe, pharmaco-therapy is largely

significant compared to placebo not only in the primary

through psycho-stimulant medications such as methylpheni-

variable 18 items of the ADHD subscale score of the SNAP-IV,

date and dexamphetamine NICE,

but also in each of the three examined domains (inattention,

Although the Italian guidelines of diagnosis and treatment of

hyperactivity/impulsivity and oppositional). A significantly

ADHD recommend the use of pharmaco-therapy for children

higher number of patients on atomoxetine compared to

and adolescents with severe and disabling ADHD (SINPIA,

placebo showed various degrees of response to therapy,

), psychotherapy and psychosocial intervention is still

consistently with the improvement observed in the ADHD

the main (often the only) type of treatment, for both ADHD

and ODD. In this trial only subjects who failed to respond to a

It should be highlighted that, despite that the results did

6-week validated and standardized behavioural management

not show initial response to the psychoeducational phase,

training for the parents of all the eligible patients were

the duration of the parental support phase was relatively

randomised to atomoxetine or placebo.

short and, therefore, potential carry-on positive effects of

This study included only paediatric patients meeting

this training program effect might have been produced

criteria for ADHD and comorbid ODD, and used a wide

during the randomized phase of the study: an informal non-

spectrum of validated outcome measures, including ADHD

structured psychoeductional support to the parents was

symptoms, ODD symptoms, comorbid anxiety and depres-

provided during the pharmacological double blind phase of

sion, problem behaviours related to ADHD (including the

the study. In the present study, treatment with atomoxetine

school setting), and emotional and social well-being of the

or placebo could be considered as an ‘add-on' therapy given

patient and the family.

in combination with the psychoeducational support. This

The manualized psychological intervention with parental

particular design might explain the, minimal or no placebo

support resulted in a very low rate of response and the mean

effects observed in the present study. With this respect, the

values of all efficacy outcome measures of the study did not

results of a recently published study conducted in Europe and

vary in this phase accordingly. In non-responder patients,

Australia (in which treatment with

treatment with atomoxetine was associated with improve-

atomoxetine or placebo of children with ADHD and comorbid

ments of symptoms of both ADHD and ODD, which resulted

ODD was not preceded by psychotherapy, showed that ADHD

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 5% of patients in any group during the randomised double blind

phase of the study.

Atomoxetine (n = 107)

Abdominal pain upper

Decreased appetite

n = number of patients; p values refer to comparisons between groups.

symptoms in the atomoxetine arm improved in a similar

the tricyclics may be mediated by the improvement in

extent to that of the present trial, whereas no significant

symptoms of ADHD. On the other hand, Spencer et al.

differences between atomoxetine and placebo were found

showed that improvements by amphetamine salts on ODD

on ODD symptoms due to a placebo effect. Similarly, in a

subscale of the SNAP-IV can be measured, even in subjects

Northern American study (), atomoxetine

with pure ODD, suggesting that the improvement in symptoms

was effective for the treatment of ADHD symptoms but

of oppositionality may be independent of any change in

appeared to not significantly reduce oppositional symptoms

ADHD symptoms. Moreover, it has also been suggested that

compared to placebo; in another study

environment can also play a crucial role on the effects of ADHD

significant improvements vs. placebo in ADHD, ODD,

medication on ODD symptoms. showed

and quality-of-life measures in patients with concomitant

that methylphenidate appears to improve symptoms of hy-

ODD symptoms were obtained at a dose level (1.8 mg/kg/

peractivity and impulsivity in a traditional classroom setting

day) higher than that of the present trial. It should also be

without significant effects on symptoms of oppositionality.

considered that although severity of ADHD and ODD

Contrarily, in a structured program of therapeutic, educa-

symptoms was similar in all the studies published (Newcorn

tional, and recreational activities, subjects appeared to

et al., ; Kaplan et al., ; Bangs et al., ;

improve with methylphenidate treatment in both their

Biederman et al., and in the present study, patients

hyperactive/impulsive and oppositional symptoms. Taken

of the Newcorn study were older (mean age 11 compared 9 of

together, these findings further suggest the independence of

the other studies), with a higher proportion of inattentive

oppositional and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms to treat-

subtype (about 30% compared to the 10% of other studies)

ment, and the crucial effect that psychoeducation interven-

and with medication administered twice a day, in compari-

tion can play on clinical efficacy of ADHD medication on ODD

son to the single daily dose of the other studies.

In the present study, pre-selected children and adoles-

In the patients with dysthymia,

cents meeting the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD (any

generalized or separation anxiety, showed a smaller reduc-

subtype) and ODD were shown to benefit from an 8-week

tion in ODD symptoms during atomoxetine treatment,

treatment with atomoxetine (and significantly compared

although excluding these patients from the overall LOCF

to a placebo control group) not only in ADHD, but also in

analysis had no effect because their small number. In the

oppositional symptoms. Additionally, the effects on ODD

present study, only few patients (approximately 20% of

symptoms were obtained at a mean atomoxetine dose (final

patients in total) presented evidence of comorbid anxiety or

dose: 1.10 ± 0.13 mg/kg/day) that approximates the mean

affective disorders, and the mean baseline scores of CDRS-R

dose used with success in ADHD symptoms in children

and SCARED were indicative of no or borderline symptoms in

and that is recommended

most of the participants. Consequently, the mean total scores

for the maintenance of symptoms' control

of both scales did change neither in the parent support phase,

nor in the randomised treatment phase in both groups.

Patients with ADHD and comorbid oppositional symptoms

The assessment of the problem behaviours related to

exhibit significantly greater ADHD symptom severity and social

ADHD, as measured by parents with the CPRS-R:S, showed that

dysfunction than ADHD patients without such comorbidity

treatment with atomoxetine was associated with improve-

A recent metanalysis (

ments in all subscales (oppositional, cognitive problems,

) suggests that much of the improvement in oppositional

hyperactivity and AHDH index) and significantly compared

symptoms by atomoxetine, pemoline, psychostimulants, or

to placebo. Similarly, patients treated with atomoxetine

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

experienced improvements of the problem behaviours related

down during the initial 6 months of treatment, but increases

to ADHD in the school environment (by teacher-rated CTRS-R:

to values close to those predicted by age and gender norms at

S), except in the cognitive problems subscale. Consistently

the end of the 2 years of observation ).

with previous published data these

The results of the open-label extension phase will provide

findings suggest that both parents and teachers are able to

further insight on the long-term safety of atomoxetine on

detect improvements in a wide spectrum of functional

growth and cardiovascular effects.

behaviours, including the school setting.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that, in

The mean CHIP-CE total score at the start of the ran-

children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD, who initially

domised phase was indicative of a moderate impairment of

did not respond to short term psychological intervention with

HRQOL, which was lower than that reported in another trial

parental support, the treatment with atomoxetine was

conducted in the UK that used the same scale

associated with improvements on symptoms of both ADHD

). Although this previous study (

and ODD measured by both parents and teachers, as well as

showed greater improvements than those observed in our

in specific aspects of quality of life and general health.

study, caution should be used in the interpretation of the

Atomoxetine exhibited a satisfactory safety profile, with

results due to the open-label design of this study and to

low incidence of dropouts and no serious adverse events

possible cross-cultural differences in the perception of

observed. The results in the open-label extension phase will

quality of life. Moreover, another analysis of effects of

assess whether the benefits observed after 8 weeks of

atomoxetine on HRQOL that used a different scale pointed

treatment are maintained in a long-term exposure to

into evidence that the likelihood of obtaining improvements

in physical functioning correlates with a worse baselineperception of HRQOL (The results of

Role of the funding source

our study showed that an HRQOL improvement was observedin some subdomains; other scores improved but did not reach

The study is fully sponsored by Eli Lilly Italy.

statistical significance maybe because of the small samplesize due to the study design based on SNAP-IV improvement.

Importantly, patients treated with atomexetine greatly

G. Dell'Agnello has written the study protocol, coordinated research

benefited in domains, such as risk avoidance or achievement,

activities and substantially contributed to data analisis and

which are considered as the most impacted ones in this

interpretation. D. Maschietto, A. Pascotto, F. Calamoneri, G. Masi,

patient population ).

P. Curatolo, D. Besana, have given their contribution to study design

The safety results of this study are consistent with those

and data collection. F. Mancini has coordinated study activities and

of previous reports. In all trials atomoxetine resulted safe

A. Rossi has contributed to data analysis and interpretation of the

and well tolerated, with discontinuations among children

results and coordinated publication's activities; L. Poole has

and adolescents due to adverse events typically less than 5%

contributed to data analysis and interpretation of the results. R.

() and with a spectrum of adverse

Escobar has contributed to study design, data interpretation and

events that are mostly mild to moderate and transient

general study coordination. A. Zuddas has substantially contributed

(; see also ). The typology of

to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation andgeneral study coordination. All authors have critically revised the

adverse events most frequently reported in this study

article and approved the manuscript before submission.

(anorexia, somnolence and gastrointestinal complaints) andtheir severity, coupled with the lack of serious adverseevents, are in line with the known safety profile of

Conflict of interest

atomoxetine in children and adolescents over variable

G. Dell'Agnello, F. Mancini, A. Rossi are full time employees at Eli

extents of exposure

Lilly Italy. L. Poole and R. Escobar are full time employees at Eli Lilly

Atomoxetine has also been previously

& Co. D. Maschietto is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Shire, has

associated with mild increases in blood pressure and pulse

received research grants from Eli Lilly. C.Bravaccio has received

that plateau during treatment and resolve upon discontin-

research grants from Eli Lilly, Shire and Astra Zeneca. F.Calamoneri

uation The noradrenergic activity of

has received research grants from Eli Lilly. G. Masi is a consultant for

atomoxetine accounts for these effects. In this study, the

Eli Lilly and Shire, has received research grants from Eli Lilly, and hasbeen speaker for Eli Lilly and Sanofi-Aventis. D. Besana is a

mean blood pressure did not vary following treatment with

consultant for Eli Lilly, has received research grants from Eli Lilly

atomoxetine, while a small increase in heart rate from the

and Janssen Cilag and has been speaker for Eli Lilly. P. Curatolo is a

start to the end of the randomised phase has been reported

consultant for Eli Lilly, and has received research grants from

in patients receiving atomoxetine, however not significantly

Janssen Cilag and Eli Lilly. D. Besana is a consultant for Eli Lilly, has

compared to placebo.

received research grants from Eli Lilly and Janssen Cilag and has

A small decrease of body weight and a slightly lower

been a speaker for Eli Lilly. A. Zuddas has an advisory or consulting

height gain compared to placebo were observed in patients

relationship with Eli Lilly, Shire, UCB and Astra Zeneca, has received

receiving atomoxetine. This could be an expected finding

research grants from Eli Lilly and Shire, and has been a speaker for

based on previous experiences, which showed that atomox-

Eli Lilly and Sanofi-Aventis.

etine may have a modest initial effect on growth rates.

However, this apparent growth-lowering effect does not

persist on a long-term exposure: a pooled analysis of data onweight and height from 13 trials in children and adolescents

The authors thank Luca Cantini and Andrea Rossi for their support in

treated with atomoxetine at usual doses for at least 2 years

medical writing of this article, Pierluigi Crisà and Roberto Pino for

has shown that mean growth rates may moderately slow

their contribution in the study organization.

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

The LYCY study group is:

effects on quality of life and school functioning. Clin. Pediatr.

Dino Maschietto, Unità Operativa di Neuropsichiatria Infantile,

(Phila) 45, 819–827.

Azienda USL 10 Veneto orientale, San Donà di Piave, Venezia;

Bukstein, O.G., Kolko, D.J., 1998. Effects of methylphenidate on

Carmela Bravaccio, Departimento di Pediatria, Università di Napoli

aggressive urban children with attention-deficit hyperactivity

"Federico II", Napoli; Filippo Calamoneri, Clinica di Neuropsichiatria

disorder. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 27, 340–351.

Infantile, Policlinico Universitario, Messina; Gabriele Masi, Divisione

Camerini, G., Coccia, M., Caffo, E., 1996. Il Disturbo da Deficit

di Neuropsichiatria Infantile, IRCCS Fondazione Stella Maris,

dell'Attenzione-Iperattività: analisi della frequenza in una

Calambrone, Pisa; Antonio Condini, Unità Operativa Autonoma di

popolazione scolastica attraverso questionari agli insegnanti.

Neuropsichiatria infanzia e adolescenza ULSS 16, Padova; Amerigo

Psichiatria. dell'infanzia. e. dell'adolescenza 63, 587–594.

Zanella, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, San Vito al Tagliamento, Pordenone;

Christman, A.K., Fermo, J.D., Markowitz, J.S., 2004. Atomoxetine, a

Giovanni Lanzi, Fondazione Mondino, Dipartimento di Clinica

novel treatment for attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder.

Neurologica e Psichiatrica dell'Età Evolutiva, Pavia; Lucia Margari,

Pharmacotherapy 24, 1020–1036.

Clinica Neurologica 2°, Sezione di Neuropsichiatria Infantile,

Conners, C.K., 1997. Conners' Rating Scales-Revised, Technical

Policlinico di Bari, Bari; Paolo Curatolo, Neuropsichiatria Infantile,

Manual. MultiHealth Systems Inc, Toronto.

Policlinico di Tor Vergata, Clinica Sant'Alessandro, Roma; Edwige

Connor, D., Glatt, S.J., Lopez, I.D., Jackson, D., Melloni, R.H., 2002.

Veneselli, Ospedale Giannina Gaslini, Genova; Dante Besana,

Psychopharmacology and aggression: I: a meta-analysis of

Struttura Operativa Complessa di Neuropsichiatria Infantile, Ospe-

stimulant effects on overt/covert aggression-related behaviors

dale Infantile, Azienda Ospedaliera Nazionale di Alessandria,

in ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 41, 253–262.

Alessandria; Anna Fabrizi, Dipartimento di Scienze Neurologiche e

Corman, S.L., Fedutes, B.A., Culley, C.M., 2004. Atomoxetine: the

Psichiatriche dell'Età Evolutiva, Università La Sapienza, Roma;

first nonstimulant for the management of attention-deficit/

Alessandro Zuddas, Clinica di Neuropsichiatria Infantile, Azienda

hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 61, 2391–2399.

Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Cagliari, Cagliari.

Escobar, R., Soutullo, C.A., Hervas, A., Gastaminza, X., Polavieja,

P., Gilaberte, I., 2005. Worse quality of life in children newlydiagnosed with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

compared with asthmatic and healthy children. Pediatrics 116,e364–369.

Aman, M.G., Kern, R.A., Osborne, P., Tumuluru, R., Rojahn, J., del

Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, L.J., Lynskey, M.T., 1993. The effects of

Medico, V., 1997. Fenfluramine and methylphenidate in children

conduct disorder and attention deficit in middle childhood on

with mental retardation and borderline IQ: clinical effects. Am.

offending and scholastic ability at age 13. J. Child. Psychol.

J. Ment. Retard. 101, 521–534.

Psychiatry 34, 899–916.

Bangs, M.E., Emslie, G.J., Spencer, T.J., Ramsey, J.L., Carlson, C.,

Fergusson, D.M., Lynskey, M.T., Horwood, L.J., 1997. Attentional

Bartky, E.J., Busner, J., Duesenberg, D.A., Harshawat, P.,

difficulties in middle childhood and psychosocial outcomes in

Kaplan, S.L., Quintana, H., Allen, A.J., Sumner, C.R., 2007.

young adulthood. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 633–644.

Efficacy and safety of atomoxetine in adolescents with attention-

Gallucci, F., Bird, H.R., Berardi, C., Gallai, V., Pfanner, P.,

deficit/hyperactivity disorder and major depression. J. Child.

Weinberg, A., 1993. Symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity

Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 17, 407–420.

disorder in an Italian school sample: findings of a pilot study. J.

Bangs, M.E., Hazell, P., Danckaerts, M., Hoare, P., Coghill, D.R.,

Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 32, 1051–1058.

Wehmeier, P.M., Williams, D.W., Moore, R.J., Levine, L., 2008.

Gaub, M., Carlson, C.L., 1997. Behavioral characteristics of DSM-IV

Atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity

ADHD subtypes in a school-based population. J. Abnorm. Child.

disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Pediatrics 121, e314–320.

Psychol. 25, 103–111.

Barkley, R.A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., Fletcher, K., 2004. Young

Geller, D., Donnelly, C., Lopez, F., Rubin, R., Newcorn, J., Sutton,

adult follow-up of hyperactive children: antisocial activities and

V., Bakken, R., Paczkowski, M., Kelsey, D., Sumner, C., 2007.

drug use. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 195–211.

Atomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-

Barkley, R.A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., Fletcher, K., 2006. Young

deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder.

adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in

J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 46, 1119–1127.

major life activities. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 45,

Guy, W., 1976. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology,

revised. Bethesda (MD), US Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare.

Biederman, J., Heiligenstein, J.H., Faries, D.E., Galil, N., Dittmann,

Hazell, P., Zhang, S., Wolanczyk, T., Barton, J., Johnson, M., Zuddas,

R., Emslie, G.J., Kratochvil, C.J., Laws, H.F., Schuh, K.J., 2002.

A., Danckaerts, M., Ladikos, A., Benn, D., Yoran-Hegesh, R.,

Efficacy of atomoxetine versus placebo in school-age girls with

Zeiner, P., Michelson, D., 2006. Comorbid oppositional defiant

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 110, e75.

disorder and the risk of relapse during 9 months of atomoxetine

Biederman, J., Spencer, T.J., Newcorn, J.H., Gao, H., Milton, D.R.,

treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur.

Feldman, P.D., Witte, M.M., 2007. Effect of comorbid symptoms

Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 15, 105–110.

of oppositional defiant disorder on responses to atomoxetine in

Hinshaw, S.P., Hencker, B., Whalen, C.K., Erhardt, D., Dunnington

children with ADHD: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trial

Jr, R.E., 1989. Aggressive, prosocial and non-social behavior in

data. Psychopharmacology 190, 31–41.

hyperactive boys: dose effects of methylphenidate in naturalistic

Birmaher, B., Khetarpal, S., Brent, D., Cully, M., Balach, L., Kaufman,

settings. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 57, 636–643.

J., Neer, S.M., 1997. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related

Hinshaw, S.P., Heller, T., Mc Hale, J.P., 1992. Covert antisocial

Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psycho-

behavior in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder:

metric characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 36,

external validation and effects of methylphenidate. J. Consult.

Clin. Psychol. 60, 274–281.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S.,

Kaplan, S., Heiligenstein, J., West, S., Busner, J., Harder, D.,

Baugher, M., 1999. Psychometric properties of the Screen for

Dittmann, R., Casat, C., Wernicke, J.F., 2004. Efficacy and safety

Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders Scale (SCARED): a

of atomoxetine in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity

replication study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 38,

disorder with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder. J. Atten.

Disord 8, 45–52.

Brown, R.T., Perwien, A., Faries, D.E., Kratochvil, C.J., Vaughan, B.S.,

Kelsey, D.K., Sumner, C.R., Casat, C.D., Coury, D.L., Quintana, H.,

2006. Atomoxetine in the management of children with ADHD:

Saylor, K.E., Sutton, V.K., Gonzales, J., Malcolm, S.K., Schuh, K.J.,

Treatment with atomoxetine of children and adolescents with ADHD and ODD

Allen, A.J., 2004. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children

Perwien, A.R., Faries, D.E., Kratochvil, C.J., Sumner, C.R., Kelsey,

with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including an assess-

D.K., Allen, A.J., 2004. Improvement in health-related quality of

ment of evening and morning behavior: a double-blind, placebo-

life in children with ADHD: an analysis of placebo controlled

controlled trial. Pediatrics 114, 1–8.

studies of atomoxetine. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 25, 264–271.

Kirley, A., Lowe, N., Mullins, C., McCarron, M., Daly, G., Waldman,

Perwien, A.R., Kratochvil, C.J., Faries, D.E., Vaughan, B.S., Spencer,

I., Fitzgerald, M., Gill, M., Hawi, Z., 2004. Phenotype studies of

T., Brown, R.T., 2006. Atomoxetine treatment in children and

the DRD4 gene polymorphisms in ADHD: association with

adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: what

oppositional defiant disorder and positive family history. Am. J.

are the long-term health-related quality-of-life outcomes?

Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet 131, 38–42.

J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 16, 713–724.

Klein, R.G., Abikoff, H., Klass, E., Ganeles, D., Seese, L.M., Pollack,

Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M.S., Horta, B.L., Biederman, J., Rohde, L.A.,

S., 1997. Clinical efficacy of methylphenidate in conduct disorder

2007. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and

with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch.

metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 942–948.

Gen. Psychiatry 54, 1073–1080.

Poznanski, E., Mokros, H.B., 1999. Children's Depression Rating

Kolko, D.J., Bukstein, O.G., Barron, J., 1999. Methylphenidate and

Scale, Revised. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles.

behavior modification in children with ADHD and comorbid ODD

Prasad, S., Harpin, V., Poole, L., Zeitlin, H., Jamdar, S., Puvanendran,

or CD: main and incremental effects across settings. J. Am. Acad.

K., The SUNBEAM Study Group, 2007. A multi-centre, randomised,

Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 38, 578–586.

open-label study of atomoxetine compared with standard current

Kuhne, M., Schachar, R., Tannock, R., 1997. Impact of comorbid

therapy in UK children and adolescents with attention-deficit/

oppositional or conduct problems on attention-deficit hyper-

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 23, 379–394.

activity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 36,

Ralston, S.J., Lorenzo, M.J., 2004. ADORE — Attention-Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder Observational Research in Europe. Eur.

Lavigne, J.V., Cicchetti, C., Gibbons, R.D., Binns, H.J., Larsen, L.,

Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 13 (Suppl 1), 36–42.

De Vito, C., 2001. Oppositional defiant disorder with onset in

Riley, A.W., Forrest, C.B., Starfield, B., Karig, M., Ensminger, M.E.,

preschool years: longitudinal stability and pathways to other

1998. A taxonomy of adolescent health need: reliability and

disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 40,

validity of the adolescent health and illness profiles. Med. Care

36, 1237–1248.

Michelson, D., Faries, D., Wernicke, J., Kelsey, D., Kendrick, K.,

Riley, A.W., Forrest, C.B., Starfield, B., Rebok, G.W., Robertson, J.A.,

Sallee, F.R., Spencer, T., 2001. Atomoxetine in the treatment of

Green, B.F., 2004. The parent report form of the CHIP-Child

children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

Edition: reliability and validity. Med. Care 42, 210–220.

disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose–response

Satake, H., Yamashita, H., Yoshida, K., 2004. The family psychosocial

study. Pediatrics 108, E83.

characteristics of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity

Michelson, D., Allen, A.J., Busner, J., Casat, C., Dunn, D., Kratochvil,

disorder with or without oppositional or conduct problems in

C., Newcorn, J., Sallee, F.R., Sangal, R.B., Saylor, K., West, S.,

Japan. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 34, 219–235.

Kelsey, D., Wernicke, J., Trapp, N.J., Harder, D., 2002. Once-

Società Italiana di NeuroPsichiatria dell'Infanzia e dell'Adolescenza

daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with

(SINPIA), 2004. Linee guida per il disturbo da deficit attentivo

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-

con iperattività (ADHD) in età evolutiva. I: Diagnosi e terapia

controlled study. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 1896–1901.

farmacologica. Giornale di Neuropsichiatria dell'età evolutiva 24

MTA Cooperative Group, 1999. Moderators and mediators of treat-

(Suppl. 1), 41–87.

ment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

Spencer, T., Biederman, J., Wilens, T., Prince, J., Hatch, M., Jones, J.,

disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 1088–1096.

Harding, M., 1998. Effectiveness and tolerability of atomoxetine

Mugnaini, D., Masi, G., Brovedani, P., Chelazzi, C., Matas, M.,

in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J.

Romagnoli, C., Zuddas, A., 2006. Teacher reports of ADHD

Psychiatry 155, 693–695.

symptoms in Italian children at the end of first grade. Eur.

Spencer, T.J., Newcorn, J.H., Kratochvil, C.J., Ruff, D., Michelson,

Psychiatry 21, 419–426.

D., Biederman, J., 2005. Effects of atomoxetine on growth after

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Brakel, A., Mayer, B., Dongen, L., 1999.

2-year treatment among pediatric patients with attention-

The Revised Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders

deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 116, 74–80.

(SCARED-R): factor structure in normal children. Person. Indiv.

Spencer, T.J., Abikoff, H.B., Connor, D.F., Biederman, J., Pliszka, S.R.,

Diff. 26, 99–112.

Boellner, S., Read, S.C., Pratt, R., 2006. Efficacy and safety

National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2000. Guidance on the use

of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) in

of methylphenidate (ritalin, equasym) for attention deficit/

the management of oppositional defiant disorder with or without

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood. Technology Appraisal,

comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged

Guidance No. 13.

children and adolescents: a 4-week, multicenter, randomized,

Newcorn, J.H., Spencer, T.J., Biederman, J., Milton, D.R.,

double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, forced-dose-es-

Michelson, D., 2005. Atomoxetine treatment in children and

calation study. Clin. Ther. 28, 402–418.

adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and

Steinhausen, H.C., Novik, T.S., Baldursson, G., Curatolo, P., Lorenzo,

comorbid oppositional defiant disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child.

M.J., Rodrigues Pereira, R., Ralston, S.J., Rothenberger, A., 2006.

Adolesc. Psychiatry 44, 240–248.

Co-existing psychiatric problems in ADHD in the ADORE cohort. Eur.

Newcorn, J.H., Michelson, D., Kratochvil, C.J., Allen, A.J., Ruff, D.D.,

Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 15 (suppl 1), 25–29.

Moore, R.J., Atomoxetine Low-dose Study Group, 2006. Low-dose

Strattera SPC (last updated on the eMC: 20/11/2008)

atomoxetine for maintenance treatment of attention-deficit/

hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 118, 1701–1706.

Oosterlaan, J., Scheres, A., Sergeant, J.A., 2005. Which executive

Swanson, J., 1992. School-Based Assessment and Interventions for

functioning deficits are associated with AD/HD, ODD/CD and

ADD. KC Publishing, Irvine, p. 184.

comorbid AD/HD+ODD/CD? J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 33, 69–85.

Taylor, E., Dopfner, M., Sergeant, J., Asherson, P., Banaschewski,

Pelham, W.E., Bender, M.E., Caddell, J., Booth, S., Moorer, S.H., 1985.

T., Buitelaar, J., Coghill, D., Danckaerts, M., Rothenberger, A.,

Methylphenidate and children with attention-deficit disorder: dose

Sonuga-Barke, E., Steinhausen, H.C., Zuddas, A., 2004. European

effects on classroom academic and social behavior. Arch. Gen.

clinical guidelines for hyperkinetic disorder — first upgrade. Eur.

Psychiatry 42, 948–952.

Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 13 (Suppl 1), I7–30.

G. Dell'Agnello et al.

van Lier, P.A., van der Ende, J., Koot, H.M., Verhulst, F.C., 2007.

Wernicke, J.F., Kratochvil, C.J., 2002. Safety profile of atomoxetine

Which better predicts conduct problems? The relationship of

in the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD. J. Clin.

trajectories of conduct problems with ODD and ADHD symptoms

Psychiatry 63 (Suppl 12), 50–55.

from childhood into adolescence. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry

Wernicke, J.F., Faries, D., Girod, D., Brown, J., Gao, H., Kelsey, D.,

48, 601–608.

Quintana, H., Lipetz, R., Michelson, D., Heiligenstein, J., 2003.

Vio, C., Offredi, G., Marzocchi, G.M., 1999. Il bambino con deficit di

Cardiovascular effects of atomoxetine in children, adolescents,

attenzione/iperattività. Trento, Edizioni Erickson.

and adults. Drug. Saf. 26, 729–740.

Weiss, M., Tannock, R., Kratochvil, C., Dunn, D., Velez-Borras, J.,

Zuddas, A., Marzocchi, G.M., Oosterlaan, J., Cavolina, P., Ancilletta,

Thomason, C., Tamura, R., Kelsey, D., Stevens, L., Allen, A.J.,

B., Sergeant, J., 2006. Factor structure and cultural factors of

2005. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of once-daily

disruptive behaviour disorders symptoms in Italian children. Eur.

atomoxetine in the school setting in children with ADHD. J. Am.

Psychiatry 21, 410–418.

Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 44, 647–655.

Source: http://cp2012.it/corsi-e-convegni/schede-eventi/atti-convegno-epidemiologia/DellAgnello%20G_2009.pdf

This compilation is for general information only and not to be used for profit or a substitute for yourtraining. Consult a professional. Please respect IP & copyright Laws. Slight variations may occur for layout purposes.Errors and omissions are not intentional, Your Host & Hostess, Chief Dave "Passing Wind" & Faith "D'Sagwagon" Substances: World Anti-Doping Code:

Medicines and Illness Policy (Boarders) 2016-2017 The following protocol has been written using the guidelines from the Handbook of School Health, Boarding Schools National Minimum Standards (April 2015), Supporting students with medical conditions (DfES Sept 2014) We aim to provide guidelines for boarding & teaching staff who find themselves in a position of responsibility regarding the storage and administration of drugs. The aim of this policy is to protect the boarding & teaching staff against any unforeseen liability. Despite the fact that many medicines are available over the counter, the boarding staff are advised by the medical centre staff only to use those which have been prescribed by a doctor or those that have been sanctioned by the school doctor or nursing staff at the medical centre (List below). This is stressed in order to protect not only the students from any errors but to protect the staff. No child under the age of sixteen should be given medicines without their parents' consent. Each child must have a completed medical form prior to starting the school which includes a declaration giving permission for nursing staff, boarding staff or teaching staff to give appropriate treatment for minor problems using non-prescription medicines. This is also authorisation for housemistress or a member of staff to approve such medical treatment as is deemed necessary in an emergency. Parents have a clear responsibility to provide the school with written details of the medicines and medical needs of their daughters. They are also expected to inform the school of any changes as they arise. Please note that if a girl has been accepted into the school without prior notification of health problems that could significantly affect the management of their daughter in the school then the school has the right to review the continuation of the student in the school. When students start or return to school, all drugs and medicines must be given to the housemistress or nurse who will dispense them as prescribed. These medications should be patient named & listed in the British National Formulary and any foreign language must be translated into English. The school medical officer will treat and prescribe for students as necessary whilst the student is in their care as a boarder Sixth Form students (i.e. those over the age of 16) may give their own consent for medical treatment. Gillick competence is used in medical law to decide whether a child (16 years or younger) is able to consent to his or her own medical treatment, without the need for parental permission or knowledge. A child will be Gillick competent if he or she has sufficient understanding and intelligence to understand fully what is proposed. The Medical Centre St. Mary's Medical Centre is staffed by registered nurses (or qualified first aider in their absence) who are available to assist student, provide first aid and advice between the hours of 08.15 – 16.00 Monday to Friday term time only. Should you wish to contact the nurses directly please telephone 01223 224169 between these hours or email