Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis

ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Vol. 44, No. 11, November 2001, pp 2531–2538

2001, American College of Rheumatology

Published by Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Effects of a Ginger Extract on Knee Pain in

Patients With Osteoarthritis

R. D. Altman1 and K. C. Marcussen2

Objective. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of a

the 2 groups. Patients receiving ginger extract experi-

standardized and highly concentrated extract of 2 gin-

enced more gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events than

ger species, Zingiber officinale and Alpinia galanga

did the placebo group (59 patients versus 21 patients).

(EV.EXT 77), in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) of the

GI adverse events were mostly mild.

Conclusion. A highly purified and standardized

Methods. Two hundred sixty-one patients with

ginger extract had a statistically significant effect on

OA of the knee and moderate-to-severe pain were en-

reducing symptoms of OA of the knee. This effect was

rolled in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-

moderate. There was a good safety profile, with mostly

controlled, multicenter, parallel-group, 6-week study.

mild GI adverse events in the ginger extract group.

After washout, patients received ginger extract or pla-

cebo twice daily, with acetaminophen allowed as rescue

Present-day therapy for osteoarthritis (OA) of

medication. The primary efficacy variable was the pro-

the knee is directed at symptoms, since there is no

portion of responders experiencing a reduction in "knee

established disease-modifying therapy. Treatment pro-

pain on standing," using an intent-to-treat analysis. A

grams involve a combination of nonpharmacologic and

responder was defined by a reduction in pain of >

15

pharmacologic measures, utilizing a combination of an-

mm on a visual analog scale.

algesia, antiinflammatory, and intraarticular programs

Results. In the 247 evaluable patients, the per-

(1–3). If these are unsuccessful, a variety of surgical

centage of responders experiencing a reduction in knee

interventions are appropriate. Since none of the medic-

pain on standing was superior in the ginger extract

inal programs consistently provides adequate relief of

group compared with the control group (63% versus

pain, yet has attendant risk, the search continues for

50%; P ⴝ

0.048). Analysis of the secondary efficacy

agents that might provide improvement in symptoms

variables revealed a consistently greater response in the

with minimal risk. While scientists have turned to the

ginger extract group compared with the control group,

investigation of newly discovered pharmaceuticals, many

when analyzing mean values: reduction in knee pain on

patients have turned to herbal and other remedies that

standing (24.5 mm versus 16.4 mm; P ⴝ

0.005), reduc-

have not been adequately studied.

tion in knee pain after walking 50 feet (15.1 mm versus

The purpose of the present study was to test an

8.7 mm; P ⴝ

0.016), and reduction in the Western

extract of

Zingiber officinale Roscoe and

Alpinia galanga

Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis com-

posite index (12.9 mm versus 9.0 mm; P ⴝ

0.087).

Linnaeus Willdenow (both are of the Zingiberaceae

Change in global status and reduction in intake of

family, commonly called "gingers"). The Zingiberaceae

rescue medication were numerically greater in the gin-

family consists of 49 genera and 1,300 species, of which

ger extract group. Change in quality of life was equal in

there are 80–90 species of

Zingiber and 250 species of

Alpinia (4). The subspecies used in the tested extract

Supported by Gra¨ngeMatic Ltd, Dublin, Ireland.

were selected after analysis and testing of ⬎100 varieties

1R. D. Altman, MD: Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center

(species and subspecies) of Zingiberaceae for antiin-

and University of Miami, Miami, Florida; 2K. C. Marcussen, MD:

flammatory effects, by in vivo assays and using animal

Narayana Research, Winter, Wisconsin.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to K. C. Mar-

models. The species selected by this process were grown

cussen, MD, Narayana Research, W 7041 Olmstead Road, Winter, WI

and harvested under controlled conditions.

Ginger is a very popular spice and the world

Submitted for publication August 23, 2000; accepted in

revised form April 11, 2001.

production is estimated at 100,000 tons annually, of

ALTMAN AND MARCUSSEN

which 80% is grown in China (5). Ginger also has a long

search based on the traditional use of the gingers has led

tradition of medicinal use and has been used as an

to the development of a patented ginger extract

antiinflammatory agent for musculoskeletal diseases,

(EV.EXT 77). In vitro experiments have shown that the

including rheumatism, in Ayurvedic and Chinese medi-

combined extract also inhibits the production of tumor

cine for more than 2,500 years (6,7). The German

necrosis factor ␣ (TNF␣) through inhibition of gene

Commission E Monographs contains reviews of drugs,

expression in human OA synoviocytes and chondrocytes

including herbal drugs, for quality, safety, and effective-

ness. As a result of this review of more than 300 herbs by

In this study, we have evaluated the safety and

an expert committee under the German Federal Insti-

efficacy of the extract in a double-blind, placebo-

tute for Drugs and Medical Devices, many herbs have

controlled study with intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

been excluded from sales in Germany. The Monographs

lists ginger for use in dyspepsia and prevention of

motion sickness (8). In the standard German text,

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Hager's Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis, ginger is

Study design. The study was a 6-week, double-blind,

listed as being used against nervousness, chronic inflam-

placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial performed at 10 clini-

mation of the intestine, coughing, conditions of the

cal centers in the US. It was designed according to guidelines

urinary tract and lower abdomen, rheumatism, and a

on conduct of clinical trials as reported by the Osteoarthritis

sore throat (9).

Research Society International (22) and as outlined in the

International Conference on Harmonisation clinical practice

Pharmacologically, ginger, similar to other plants,

guidelines (23). The protocol followed the 1975 Declaration of

is a very complex mixture of compounds.

Zingiber offi-

Helsinki as revised in 1983, with institutional review board

cinale contains several hundred known constituents (10),

approval, and all patients provided their oral and written

among them gingeroles, beta-carotene, capsaicin, caffeic

informed consent. Patients were centrally randomized to re-

acid, and curcumin. In addition, salicylate has been

ceive treatment by a computer-generated allocation schedule,

balanced by center, and both the investigators and the patients

found in ginger in amounts of 4.5 mg/100 gm fresh root

were blinded to treatment assignment.

(11). This would correspond to ⬍1 mg salicylate in 1

Patients. Patients had OA of the knee by the American

capsule of the presently tested ginger extract. The

College of Rheumatology classification criteria using the deci-

actions and especially the interactions of these ingredi-

sion tree format that includes radiographs (24). The radio-

ents have not been (and probably can not be easily)

graphic changes had to include at least osteophytes and

evaluated. Various powders, formulations, and extracts

correspond to OA grades 2, 3, or 4 by the Kellgren and

Lawrence criteria (25).

have, however, been commercially used and tested, both

Admission criteria included the presence of knee pain

in vitro and in vivo, in animal models. In these models,

on standing that had to be between 40 mm and 90 mm on a

ginger has been shown to act as a dual inhibitor of both

100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) during the preceding 24

cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipooxygenase (12), to in-

hours. This was assessed after a 1-week washout period. Both

hibit leukotriene synthesis (13), and to reduce

men and women ⱖ18 years old were included. Pain had to be

of a degree so that it could be tolerated with alleviation using

caregeenan-induced rat-paw edema (14,15), an animal

acetaminophen as an escape medication for 6 weeks. Prior

model of inflammation.

treatment for OA was not a requirement. Patients with any of

Another related plant, galanga, commonly called

the following were excluded: rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyal-

greater galanga, is also widely used as a spice in the East

gia, gout, recurrent or active pseudogout, cancer or other

and as a remedy for various ailments. It has an antiin-

serious disease, signs or history of liver or kidney failure,

asthma requiring treatment with steroids, treatment with oral

flammatory action through inhibition of prostaglandin

corticosteroids within the prior 4 weeks, intraarticular knee

synthesis (16), and has traditionally been used for rheu-

depo-corticosteroids within the previous 3 months, intraartic-

matic conditions in South East Asian medicine (17). The

ular hyaluronate within the previous 6 months, prior treatment

volatile oil of

Alpinia galanga L., which can be obtained

with immunosuppressive drugs such as gold or penicillamine,

by steam distillation of the rhizome, is a complex mixture

arthroscopy of the target joint within the previous year,

significant injury to the target joint within the previous 6

containing 1,8-cineol and 1⬘-acetoxychavicol acetate

months, other investigational drugs within the previous 1

which has antifungal (18) and antitumor (19) activity.

month, fever ⬎38°C at screening, and allergy to acetamino-

The German Commission E Monographs lists the use of

phen or ginger.

Alpinia officinarum, which is closely related to

Alpinia

After screening, patients entered a 1-week "washout"

galanga, for dyspepsia and loss of appetite. The US Food

for antiinflammatory and analgesic medications, during which

they were allowed to take acetaminophen as needed up to 4

and Drug Administration lists ginger and

Alpinia offici-

gm/day. Aspirin for anticoagulation up to 325 mg daily was

narum as "generally regarded as safe" (20). New re-

allowed throughout the study.

GINGER EXTRACT IN OA OF THE KNEE

If patients were determined to be eligible for the study,

coded according to World Health Organization adverse reac-

a baseline assessment of pain was performed after washout of

tion terminology (28). The adverse events were analyzed by

medications that would affect the arthritis and prior to ran-

preferred terms and by system organ classes.

domization. Each center was block-randomized with 130 pa-

Statistical analysis. Blinding was maintained until the

tients receiving ginger extract and 131 patients receiving

final database was cleaned and locked. However, there was an

interim analysis of 116 patients that was performed at a

Treatment. During the 6-week treatment period, pa-

significance level of 0.01% by an independent statistician. The

tients ingested 1 capsule twice daily, morning and evening.

results were disclosed to the sponsor only. Neither the inves-

Each capsule contained 255 mg of EV.EXT 77, extracted from

tigators nor the clinical research organization monitoring the

2,500–4,000 mg of dried ginger rhizomes and 500–1,500 mg of

study were aware of the results.

dried galanga rhizomes and produced according to good

Sample-size calculation was based on results of an

manufacturing practice (Eurovita Holding, Karlslunde, Den-

unpublished clinical trial using a ginger extract. Statistical

mark). Matching placebo capsules contained coconut oil. To

evaluation was performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary,

minimize a possible pungent sensation, patients were in-

NC). The statistical analysis was performed using analysis of

structed to swallow the whole (intact) capsule with a glassful of

covariance for analysis of means, with baseline scores, center,

water at the time of a meal.

sex, treatment-by-center interaction, and age as the covariates.

Acetaminophen was permitted as a rescue medication.

Chi-square tests were used for analysis of responders, Stu-

Patients were instructed to take the rescue medication only

dent's

t-test to analyze intake of rescue medication, and

when needed, to a maximum dosage of 2 tablets 4 times daily,

Fisher's exact test for comparing incidence of adverse events

i.e., 4 gm/day.

between groups. Except for the analysis of intake of rescue

Drug accountability was calculated by pill count for

medication, the ITT last observation carried forward method

both the study treatment and the rescue medication.

was used. All analyses were performed 2-sided, with a mini-

Assessments. The OA knee deemed to be more symp-

tomatic was defined as the target joint by the investigator, and

mum significance level of 5%.

the knee-specific pain was assessed for this joint. The primary

efficacy parameter was the proportion of responders experi-

encing at least a 15-mm reduction in pain between baseline and

the final visit for knee pain on standing during the preceding 12

Patients. There was no clinically relevant differ-

hours, as measured by a 100-mm VAS. Pain on standing is a

ence in the demographics between the 2 treatment

validated measure of pain and coincides with question 5 of the

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) OA

groups (Table 1). The patients were predominantly

composite index (26). At the time of the design of this study,

women and predominantly white. Patients in both study

the full WOMAC index was not generally accepted as a

groups were generally overweight, since the average

primary efficacy variable in clinical trials of OA of the knee.

body mass index was ⬎30 kg/m2 (range 18–65 kg/m2).

Secondary efficacy measures that were used to com-

All patients with at least 1 visit after the baseline

pare the 2 study groups were as follows: 1) average improve-

ment in pain on standing, as measured by a 100-mm VAS; 2)

evaluation were included in the ITT analysis. Fourteen

consumption of rescue medication; 3) WOMAC index as

patients, 8 receiving placebo and 6 receiving ginger

measured by VAS, with one end of the scale being "no

extract, discontinued the trial before completing any

pain/stiffness/difficulty" and the other end, "extreme pain/

evaluation of efficacy. Among the patients in the pla-

stiffness/difficulty" (the total score was calculated as the mean

response); 4) patient assessment of global status, in which the

cebo group who discontinued, 3 dropped out due to

question, "Given all the ways your osteoarthritis affects you,

adverse events, 4 were lost to followup, and 1 withdrew

how have you been doing the last 24 hours?" was evaluated on

consent. Among the patients receiving ginger extract

a 5-point Likert scale (1 ⫽ very poor, 2 ⫽ poor, 3 ⫽ average,

who discontinued, 3 dropped out due to adverse events

4 ⫽ good, 5 ⫽ very good); 5) quality of life assessment using

and 3 were lost to followup. Thus, the modified ITT

the Short Form 12 (SF-12), which asks questions regarding the

patient's condition during the preceding 4 weeks (27); and 6)

analysis included the 247 patients (95% of the total

pain in the knee after walking 50 feet, recorded immediately

enrolled) who completed any postbaseline efficacy eval-

after walking and measured by a 100-mm VAS.

uation. A total of 194 patients (74%) completed the

Efficacy and safety assessments were performed at

study without protocol violations. Fifty-seven patients

baseline and after 2 and 6 weeks of treatment. The SF-12 was

administered at screening and after 6 weeks of treatment only.

discontinued prematurely (22% of the randomized pop-

Safety was assessed via open-ended questions concerning

ulation) (Table 2). The overall withdrawal rate was 28%

changes in the patients' health at each visit, supported by

in the ginger extract group and 16% among those

patients' responses on diary cards. For all adverse events, the

receiving placebo. The withdrawal rate due to adverse

onset, duration, and intensity (mild, moderate, or severe) of

events was 13% in the ginger extract group and 5% in

the event, as well as the action taken and outcome, were

recorded. The relationship between an adverse event and the

the placebo group. There were no followup data avail-

study medication was assessed, by the investigator, as none,

able for the patients who withdrew from the study

remote, possible, probable, or definite. Adverse events were

ALTMAN AND MARCUSSEN

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study population*

Age, mean ⫾ SD years

Body mass index, mean ⫾ SD kg/m2

Diagnosed OA, mean ⫾ SD years

Radiographic classification of

* OA ⫽ osteoarthritis.

† By the Kellgren and Lawrence criteria (25).

Compliance. Compliance was calculated from the

extract group (78 of 130, or 60%) than in the placebo

amount of study medication (number of capsules) re-

group (62 of 131, or 47%) (P ⫽ 0.040). The analysis of

turned and the number of empty slots in the blister

means for pain on standing showed that the ginger

cards. Compliance was 98 ⫾ 12% (mean ⫾ SD) for the

extract group improved an average 8.1 mm more than

ginger extract group and 98 ⫾ 18% for the placebo

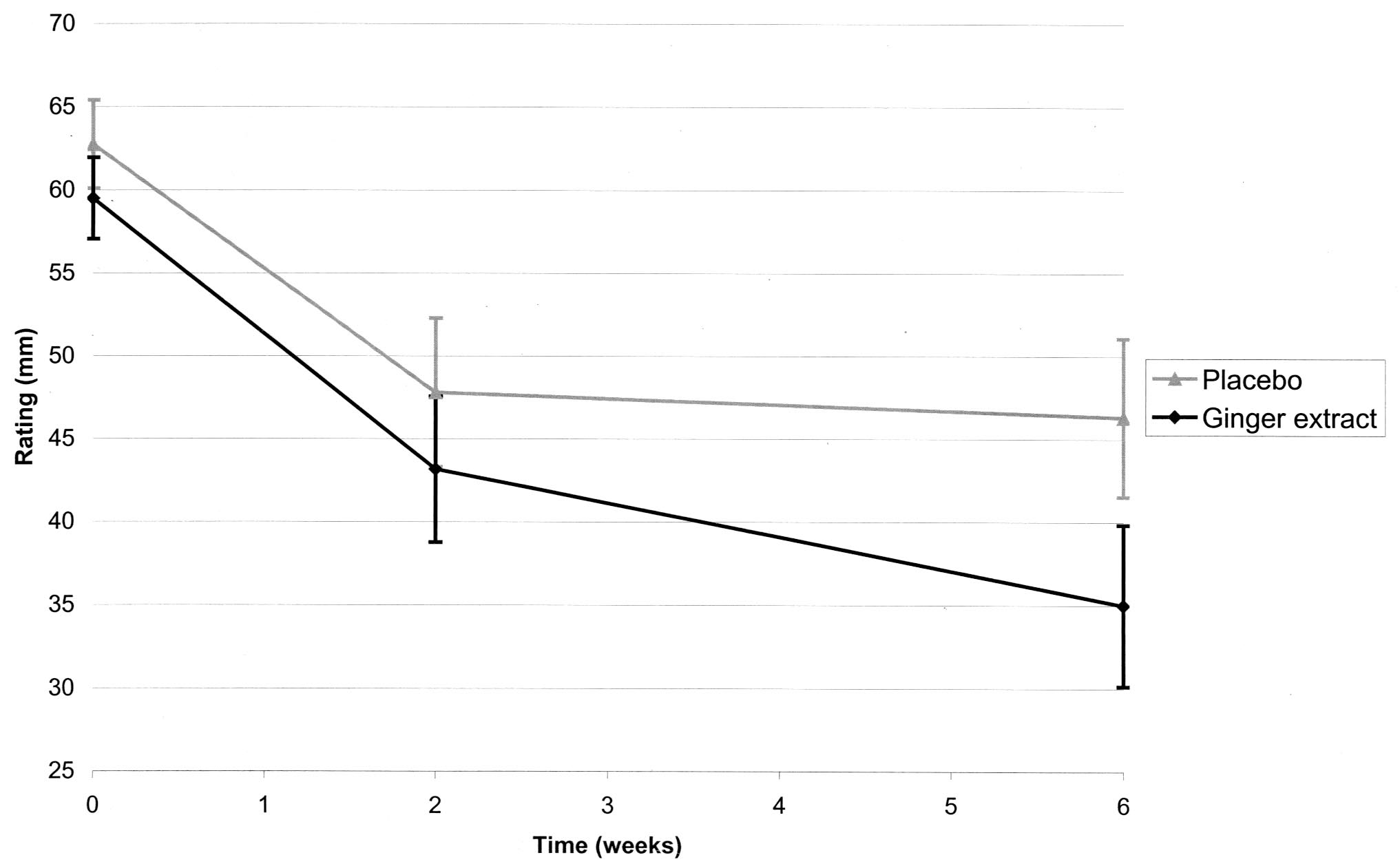

did the placebo group (P ⫽ 0.005) (Figure 1).

A subset analysis was performed for increased

Primary efficacy variable: pain on standing. Pain

responder levels. For ⱖ20-mm improvement in pain on

on standing after 6 weeks of treatment showed improve-

standing, the ginger extract group showed a response

ment in both treatment groups. However, as the primary

superior to that of the placebo group (n ⫽ 73 [59%]

efficacy parameter, there was a higher percentage of

versus n ⫽ 56 [46%]; P ⫽ 0.036). For a ⱖ25-mm

responders (improvement ⱖ15 mm on the VAS pain

improvement, the ginger extract group again displayed a

scale) in the ginger extract group (n ⫽ 78 [63%]) than in

the placebo group (n ⫽ 62 [50%]; P ⫽ 0.048). An ITT

analysis of all patients enrolled, regardless of whether

they underwent any postbaseline efficacy evaluation,

also showed a higher rate of responders in the ginger

Table 2. Discontinuations among the randomized population*

Primary reason for

early termination

Perceived lack of efficacy

Intercurrent illness

Figure 1. Knee pain on standing as measured by 100-mm visual

analog scale after 2 and 6 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis

receiving placebo (n ⫽ 123) or ginger extract (n ⫽ 124), in the

* Values are the number of patients.

intent-to-treat analysis. Bars show the mean pain rating (in mm) and

† P ⫽ 0.025 versus placebo.

95% confidence intervals.

GINGER EXTRACT IN OA OF THE KNEE

Table 3. Results of secondary parameters in the intent-to-treat analysis

Placebo (n ⫽ 123)*

Ginger extract (n ⫽ 124)*

Pain after walking 50 feet

* Numbers of patients vary between 121 and 124 at the single visits, and for quality of life (QOL), between 111 and 114.

† Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) consists of 24 questions, assessed on 100-mm visual analog scale,

analyzed in 3 subscales as the average score for 5 questions on pain, 2 questions on stiffness, and 17 questions on function. The total score is

calculated as the mean score for all 24 questions.

‡ The Short Form 12 (SF-12) consists of 12 questions that are combined into 8 scales, which are summarized in the physical and mental component

summaries shown here.

superior response compared with that of the placebo

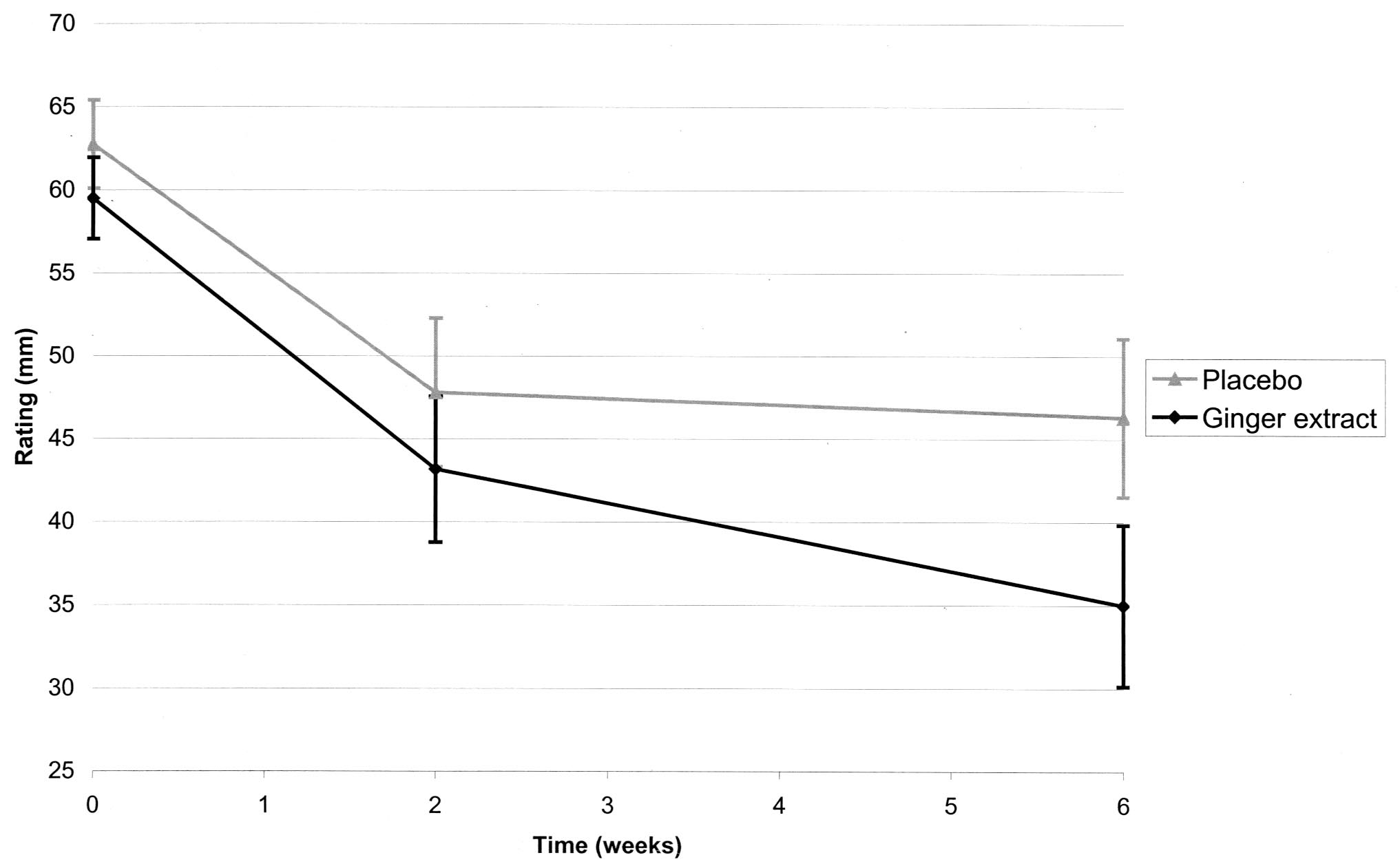

Figure 2 shows the response on the individual questions

group (n ⫽ 65 [52%] versus n ⫽ 48 [39%]; P ⫽ 0.035).

of the WOMAC questionnaire, with responses to ques-

In an analysis of the patients who completed the

tions 6, 7, 11, 14, and 15 showing a significant improve-

study per protocol and experienced ⱖ15-mm improve-

ment among patients receiving the ginger extract. Im-

ment in pain on standing, results were similar to those of

provement in patient global status was numerically

the ITT analysis, although the difference between the 2

better in the ginger extract group and was statistically

treatment groups was smaller. The ginger extract group

superior in a per protocol analysis (P ⫽ 0.042). There

showed a response that was numerically superior (60 of

was no difference in the SF-12 score, since there was

92, or 65%) to that of the placebo group (54 of 102, or

little change from baseline in either group. Acetamino-

53%) (P ⫽ 0.083). In other parameters, significant

phen use was equal in the 2 study groups (mean ⫾ SD

improvements comparable with those in the ITT analysis

number of tablets daily 2.0 ⫾ 1.9 in the ginger extract

group and 2.2 ⫾ 2.0 in the placebo group).

Secondary efficacy variables. The results of the

Analysis of individual variables showed no effect

secondary parameters were consistent with the findings

of age (⬎65 years versus ⬍65 years), sex, center, or

with the primary parameter (Table 3). Pain after walking

treatment-per-center interaction on the efficacy para-

also demonstrated a significant improvement in the

meters. This analysis did show a difference in the

ginger extract group compared with the placebo group.

baseline scores, especially in global status, with the

The change in total WOMAC score was numerically

placebo group having the worse scores. This difference

superior in the ginger extract group versus the placebo

cannot be explained, but it was adjusted for through the

group, with the greatest improvement seen in stiffness.

analysis of covariance.

ALTMAN AND MARCUSSEN

There was concern that the adverse events might

affect the blinding of treatment status. Therefore, we

examined the percentage of responders for pain on

standing in the ginger extract group in the presence or

absence of GI adverse events. There were 65% respond-

ers in the presence of dyspepsia, eructation, or nausea,

and 62% responders in the absence of these adverse GI

events (P ⫽ 0.85). Through this analysis, the adverse

events were not found to significantly affect the outcome

of the study.

Patients were informed about the possible pun-

gency upon entering the study. Experience of the pun-

gent taste was captured as adverse events to an extent,

Figure 2. Mean change from baseline to the fourth visit in each

which may explain the incidence of these events. Still,

functional measure of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universi-ties osteoarthritis index for the 2 treatment groups, in the intent-to-

the possibility exists that some subjects were not truly

treat analysis. Bars show the mean and standard error.

blinded due to the pungency of the ginger extract.

Adverse events. There were 314 adverse events

reported on diary cards and by questioning. Seventy-six

In a 1999 Gallup questionnaire among Ameri-

patients (59%) receiving ginger extract experienced 202

cans with arthritis, 28% thought that herbals have a role

adverse events. Forty-nine patients (37%) receiving pla-

in the treatment of arthritis, and 17% believed that

cebo experienced 112 adverse events. Only 1 group of

herbals have a preventative role (29). In a 1997 US

adverse events showed a significant difference between

survey among 2,055 people, 27% of those with arthritis

the treatment groups: gastrointestinal (GI) adverse

had used an alternative treatment for the disease within

events were more common in the ginger extract group

the last year (30). Herbal remedies and other nutraceu-

(116 events in 59 patients [45%]) compared with the

ticals or botanicals are thus increasingly used by both the

placebo group (28 events in 21 patients [16%]).

healthy and the sick. Unfortunately, few of the remedies

None of the GI adverse events were considered

have been tested for efficacy and safety in well-designed

serious by the investigators; 70% were reported as mild,

clinical trials.

24% moderate, and 6% severe. When analyzing the

In order to address this issue, in a 6-week,

events by preferred terms, the only events seen signifi-

randomized clinical trial using ITT analysis in patients

cantly more often in the ginger extract group were

with OA of the knee, treatment with a ginger and

eructation, dyspepsia, and nausea. Words used by the

galanga extract (EV.EXT 77) demonstrated a reduction

patients included burping, belching, bad taste in the

in knee pain on standing when compared with patients

mouth, stomach upset, heartburn, and a burning sensa-

receiving placebo. Additional analyses of the primary

tion in the stomach. To examine whether preexisting

efficacy variable as well as changes in the WOMAC

conditions had any influence on this response, the

index and global status were consistent with the results

patients' medical history was related to the adverse

of the primary efficacy variable. In this short-term study,

events. Thirty-six patients in each treatment group had a

there was no essential difference in the ginger and

previous diagnosis of reflux disease, dyspepsia, ulcer,

placebo groups for quality of life (measured by the

heartburn, gastritis, or hiatus hernia. Of these, 4 patients

SF-12) or consumption of rescue analgesia (acetamino-

(11%) in the placebo group and 10 (28%) receiving

phen). The treatment group also had an increase in GI

ginger extract had at least 1 of the adverse events, including

adverse events.

dyspepsia, eructation, or nausea; it was concluded that

The benefits found in this trial are consistent with

there was no connection to previous conditions.

the results described in the few existing reports in the

There was no statistically significant difference

literature. Three published studies on the use of ginger

between the number of severe adverse events in the 2

in arthritis have been identified. Two were collections of

treatment groups. One serious adverse event occurred in

anecdotal reports (31,32). In the larger cohort, involving

the study, a myocardial infarction in a patient receiving

56 patients with rheumatic disorders, more than 75%

experienced relief of pain and swelling after an average

GINGER EXTRACT IN OA OF THE KNEE

dosage of 3 gm raw ginger per day for periods varying

or bleeding after intake of ginger despite widespread use

between 3 months and 2 years (32). A randomized

of ginger throughout the world. Surprisingly, both ginger

clinical trial included 67 patients, of whom 56 were able

(38) and galanga (39) have been shown to protect

to be evaluated (33). This was a 3-way, crossover study

against ulcers in animal studies. The lack of severe GI

comparing ibuprofen, ginger extract, and placebo. The

adverse events seen in this study is consistent with the

ranking of efficacy was ibuprofen ⬎ ginger extract ⬎

observations in the above-mentioned studies as well as in

placebo for VAS scores on pain and the Lequesne index,

studies on other uses of ginger: seasickness (40), post-

but no significant difference was seen when comparing

operative antiemetic (41,42), and vertigo (43).

ginger extract and placebo directly. Exploratory testing

A warning has been reported on the possible

of the first period of treatment (before crossover) was

effect of ginger on bleeding time (44). In vitro studies

performed and this showed a better effect of both

have shown that ginger inhibits thromboxane synthesis

ibuprofen and ginger extract compared with that of

and thereby platelet aggregation (45). In humans, an ex

placebo (P ⬍ 0.05 by chi-square test).

In the WOMAC subgroups in the present study,

vivo study tested a single dose of 2 gm dried ginger (46).

the greatest improvement was seen in stiffness. The

Another 3-way crossover study compared the oral intake

WOMAC index is described as being more sensitive to

of 15 gm raw ginger/day, 40 gm cooked stem ginger/day,

change in pain, followed by stiffness and function (34).

and placebo for 2 weeks in 18 healthy volunteers (47).

Further investigation into the effects of ginger on stiff-

None of the tested ginger preparations produced any

ness appears warranted, since this may indicate a differ-

significant change in thromboxane synthesis. We could

ent mechanism of action than most other OA remedies.

find no published data on adverse events connected with

This was a short-term study. At 6 weeks, the

coagulation with ginger.

placebo effect appeared to fade, whereas the group

The average body mass index for this study

treated with ginger extract continued to improve.

population was high. Patients were enrolled without

Longer-term studies are needed.

weight restrictions and may constitute a typical OA

Although the COX-2–specific inhibitors have less

population in the US. The dosing of the ginger extract

GI adverse effects than do nonselective nonsteroidal

given was empirically based on the 1–2 capsules per day

antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), their overall safety

that is typically consumed in Europe. In retrospect,

versus placebo is not entirely known, and there are no

there may be concern that the US patients may have

studies comparing COX-2–specific inhibitors with the

been underdosed. Without a dose-finding study, it is

ginger extract. Both nonselective NSAIDs and COX-2–

uncertain if a higher dose would have a better effect.

specific inhibitors have potential renal adverse effects

In conclusion, this study showed that a highly

(35) not described with the ginger extracts.

purified ginger extract has demonstrated a statistical

Some of the patients reported mild GI side

effect of reducing pain in patients with OA of the knee.

effects in the form of dyspepsia, eructation, and nausea.

There was a good safety profile with mostly mild GI side

These may be caused by the pungent taste of the ginger

effects. Long-term effects bear further investigation.

extract. Adverse events for NSAIDs can be classified

into 3 categories (36): 1) "nuisance" symptoms, such as

heartburn, nausea, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain; 2)

mucosal lesions; and 3) serious GI complications, such

We thank Dr. Fong Wang Clow for preparing the

as bleeding and perforation. On average, 10–12% of

statistical plan and Rebecca Hoagland for performing the

patients will experience dyspepsia while taking a nonse-

statistical analysis. In addition to Dr. Altman, contributing

lective NSAID, sometimes leading to death (36,37).

investigators were as follows: Neal Birnbaum, MD, Pacific

Rheumatology Associates, San Francisco, California; Lon Bla-

Because ginger inhibits prostaglandin synthesis, there is

ser, MD, Marshfield Clinic, Marshfield, Wisconsin; Jacque

the potential for GI ulceration. However, the effect of

Caldwell, MD, Halifax Clinical Research Institute, Daytona

NSAIDs on the inflammatory process is mainly caused

Beach, Florida; Guy Fiocco, MD, Gundersen Lutheran Clinic,

by inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Contrary to this,

La Crosse, Wisconsin; Elie Gertner, MD, Regions Hospital, St.

the ginger extract is a complex mixture that reduces

Paul, Minnesota; Larry Gilderman, MD, University Clinical

inflammation through inhibition of prostaglandin syn-

Research, Pembroke Pines, Florida; Robert Leff, MD, Duluth

Clinic, Duluth, Minnesota; Howard Offenberg, MD, Halifax

thesis, inhibition of lipooxygenase (13), and reduced

Clinical Research Institute, New Smyrna Beach, Florida; and

production of TNF␣ (21).

Albert Razetti, MD, University Clinical Research, Deland,

We could find no data indicating mucosal lesions

ALTMAN AND MARCUSSEN

al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of

osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis

1. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, Brandt KD, Clark BM, Dieppe PA,

Griffin MR, et al. Guidelines for the medical management of

25. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteoarthri-

osteoarthritis: part II. osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum

tis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16:494–501.

26. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW.

2. Lozada CJ, Altman RD. Management of osteoarthritis. In: Koop-

Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for

man WJ, editor. Arthritis and allied conditions: a textbook of

measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to anti-

rheumatology. 14th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott, Williams &

rheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or

Wilkins; 2001. p. 2246–63.

knee. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1833–40.

3. Pendleton A, Arden N, Dougados M, Doherty M, Bannwarth B,

27. Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Keller SD. A 12-item Short Form Health

Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for therapy of knee

Survey. Med Care 1996;34:220–33.

osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for

28. Adverse reaction terminology. Uppsala: Uppsala Monitoring Cen-

International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ES-

CISITO). Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:936–44.

29. The 1999 Gallup Trend Study of Attitudes Toward and Use of

4. Trease GE, Evans WC, editors. Pharmacognosy. 12th ed. London

Herbal Supplements. Princeton, NJ: Multi-sponsor Surveys Inc.;

(UK): Bailliere Tindall; 1983.

5. Langner ES, Griefenberg S, Gruenwald J. Ingwer: eine Heil-

30. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Rompay

pflanze mit Geschichte [Ginger: a medicinal plant with a history].

M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States,

Balance Z Prax Wiss Komplementarer Ther 1997;1:5–16.

1990–1997. JAMA 1998;280:1569–75.

6. Awang D. Ginger. Can Pharm J 1992:309–11.

31. Srivastava KC, Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and rheu-

7. Tschirch A. Handbuch der Pharmakognosie [A handbook of

matic disorders. Med Hypotheses 1989;29:25–8.

pharmacognosy]. Leipzig: Verlag CH Tauchnitz; 1917.

32. Srivastava KC, Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in rheu-

8. Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, Gruenwald J, Hall T,

matism and musculoskeletal disorders. Med Hypotheses 1992;39:

Riggins W, et al, editors. German Commission E Monographs.

Austin (TX): American Botanical Council; 1998.

33. Bliddal H, Rosetzsky A, Schlichting P, Weidner MS, Anderson

9. Blaschek W, Hager H, Ha¨nsel R, Wolf HU, Surmann P, Nyrnberg

LA, Ibfelt H, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over

E, et al. Hager's Handbuch der pharmazeutischen Praxis. 5th rev.

study of ginger extracts and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. Osteoar-

ed. Berlin-New York: Springer Verlag; 1990.

thritis Cartilage 2000;8:9–12.

10. Schulick P. Ginger, common spice and wonder drug. 3rd ed.

34. Bellamy N. WOMAC user's guide. London (Ont): Victoria Hos-

Brattleboro (VT): Herbal Free Press Ltd; 1996.

pital Corporation; 1996.

11. Swain AR, Duton SP, Truswell AS. Salicylates in foods. J Am Diet

35. Brater DC. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on

renal function: focus on cyclooxygenase-2-selective inhibition. Am

12. Mustafa T, Srivastava KC, Jensen KB. Drug development: report

J Med 1999;107:65–71.

9. Pharmacology of ginger, Zingiber officinale. J Drug Dev

36. Bjorkman DJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gas-

trointestinal injury. Am J Med 1996;101 Suppl 1A:25–32.

13. Kiuchi F, Iwakami S, Shibuya M, Hanaoka F, Sandawa U. Inhibition

37. Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Epidemiology of NSAID induced

of prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis by gingeroles and

gastrointestinal complications. J Rheumatol 1999;26:18–24.

diarylheptanoids. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1992;40:187–91.

38. Al-Yahya MA, Rafatullah S, Mossa JS, Ageel AM, Parmar NS,

14. Mascolo N, Jain R, Jain SC, Capasso F. Ethnopharmacological

Tariq M. Gastroprotective activity of ginger zingiber officinal

investigation of Ginger (Zingiber officinale). J Ethnopharmacol

rosc., in albino rats. Am J Chin Med 1989;17:51–6.

39. Mitsui S, Kobayash S, Nagahori H, Ariba O. Constituents from

15. Jana U, Chattopadhayay RN, Shaw BP. Preliminary studies on

seeds of Alpinia galanga Wild, and their anti-ulcer activities. Chem

anti-inflammatory activity of Zingiber officinale Rosc., Vitex

Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1976;24:2377–82.

negundo Linn. and Tinospora cordifolia (Willid) miers in albino

40. Groentved A, Brask T, Kambskard J, Hentzer E. Ginger root

rats. Indian J Pharmacol 1999;31:232–3.

against seasickness. Acta Otolaryngol 1998;105:45–9.

16. Rhizoma galangae. Ko¨ln: Bundesanzeiger [Federal German Legal

41. Bone ME, Wilkinson DJ, Young JR, McNeil J. Ginger root—a

Gazette]; 1990 Mar 13. Commission E monograph No.: 173.

new antiemetic: the effect of ginger root on postoperative nausea

17. Perry L, Metzger J. Medicinal plants of east and southeast Asia:

and vomiting after major gynecological surgery. Anaesthesia 1990;

attributed properties and uses. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 1980.

18. Janssen AM, Scheffer JJC. Acetoxychavicol acetate, an antifungal

42. Philips S. Zingiber officinale (ginger)—an antiemetic for day case

component of Alpinia galanga. Planta Med 1985;6:507–11.

surgery. Anaesthesia 1993;48:715–7.

19. Itokawa H, Morita H, Sumitomo T, Totsuka N, Takeya K.

43. Groentved A, Hentzer E. Vertigo-reducing effect of ginger root. J

Antitumor principals from Alpinia galanga. Planta Med 1987;53:

Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1986;48:282–6.

44. Miller LG. Herbal medicinals: selected clinical considerations

20. Substances generally regarded as safe, 21 CFR Section 182.10,

focusing on known or potential drug-herb interactions. Arch

182.20. Washington (DC): GPO; 1998.

Intern Med 1998;158:2200–11.

21. Frondoza CG, Frazier C, Polotsky A, Lahiji K, Hungerford DS,

45. Srivastava KC. Effects of aqueous extracts of onion, garlic and

Weidner MS. Inhibition of chondrocyte and synoviocyte TNF␣

ginger on platelet aggregation and metabolism of arachidonic acid

expression by hydroxy-alcoxy-phenyl compounds (HAPC) [ab-

in the blood vascular system: in vitro study. Prostaglandins Leukot

stract]. Trans Orthop Res Soc 2000:1038.

22. Altman RD, Brandt K, Hochberg M, Moskowitz R. Design and

46. Lumb AB. Effect of dried ginger on human platelet function.

conduct of clinical trials in patients with osteoarthritis. Osteoar-

Thromb Haemost 1994;71:110–1.

thritis Cartilage 1996;4:217–43.

47. Janssen PLTMK, Meyboom S, van Staveren WA, de Vegt F,

23. International Conference on Harmonisation. Good clinical prac-

Katan MB. Consumption of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe)

tice. Geneva: ICH Secretariat; 1996 May 1. Efficacy Topic: E6.

does not affect ex vivo platelet thromboxane production in hu-

24. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et

mans. Eur J Clin Nutr 1996;50:772–4.

Source: http://www.im-care.cn/UpLoadFiles/%E4%B8%93%E9%A2%98%E6%96%87%E7%8C%AE/%E6%B2%BB%E5%85%B3%E8%8A%82%E7%82%8E/12%E7%94%9F%E5%A7%9C%E6%8F%90%E5%8F%96%E7%89%A9%E5%AF%B9%E9%AA%A8%E5%85%B3%E8%8A%82%E7%82%8E%E6%82%A3%E8%80%85%E7%9A%84%E4%BD%9C%E7%94%A8.pdf

Egg Thaw Cycle Orientation Visit us online at www.NYUFertilityCenter.org Copyright 2008 – 2013 NYU Fertility Center – rev. 06/05/2013 Meet Our Physicians Dr. Frederick Licciardi Dr. James Grifo Dr. Nicole Noyes Dr. Alan Berkeley Dr. Lisa Kump-Checchio Dr. M. Elizabeth Fino Dr. David Keefe

The Medication Therapy Management approach is a progressive model of prescription utilization and consumer centered purchase options. The program offers the consumer a variety of options for prescription access and out of pocket cost management. Over the Counter, generic, best brand, non-best brand, and cost share prescriptions are available. Step therapy, prior authorization management tools are incorporated into the program to assist in managing prescription costs; evidence based prescription approaches with clinical excellence as an outcome objective. Enclosed are the prescription resources to assist in effective prescription purchasing.