Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Microsoft word - 33 models of causation - health determinants

Health Determinants

Core Body of Knowledge for the Generalist OHS Professional

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

Copyright notice and licence terms

First published in 2012 by the Safety Institute of Australia Ltd, Tullamarine, Victoria, Australia.

ISBN 978-0-9808743-1-0

This work is copyright and has been published by the Safety Institute of Australia Ltd (SIA) under the

auspices of HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals Alliance). Except as may be expressly provided by law

and subject to the conditions prescribed in the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth of Australia), or as

expressly permitted below, no part of the work may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

microcopying, digital scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted without prior written permission of the SIA.

You are free to reproduce the material for reasonable personal, or in-house, non-commercial use for the

purposes of workplace health and safety as long as you attribute the work using the citation guidelines below

and do not charge fees directly or indirectly for use of the material. You must not change any part of the work

or remove any part of this copyright notice, licence terms and disclaimer below.

A further licence will be required and may be granted by the SIA for use of the materials if you wish to:

· reproduce multiple copies of the work or any part of it · charge others directly or indirectly for access to the materials · include all or part of the materials in advertising of a product or services, or in a product for sale · modify the materials in any form, or · publish the materials.

Enquiries regarding the licence or further use of the works are welcome and should be addressed to:

Registrar, Australian OHS Education Accreditation Board

Safety Institute of Australia Ltd, PO Box 2078, Gladstone Park, Victoria, Australia, 3043

Citation of the whole Body of Knowledge should be as:

HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals Alliance).(2012). The Core Body of Knowledge for Generalist OHS Professionals. Tullamarine, VIC. Safety Institute of Australia.

Citation of individual chapters should be as, for example:

Pryor, P., Capra, M. (2012). Foundation Science. In HaSPA (Health and Safety Professionals

Alliance), The Core Body of Knowledge for Generalist OHS Professionals. Tullamarine, VIC.

Safety Institute of Australia.

Disclaimer

This material is supplied on the terms and understanding that HaSPA, the Safety Institute of

Australia Ltd and their respective employees, officers and agents, the editor, or chapter authors and

peer reviewers shall not be responsible or liable for any loss, damage, personal injury or death

suffered by any person, howsoever caused and whether or not due to negligence, arising from the

use of or reliance of any information, data or advice provided or referred to in this publication.

Before relying on the material, users should carefully make their own assessment as to its accuracy,

currency, completeness and relevance for their purposes, and should obtain any appropriate

professional advice relevant to their particular circumstances.

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

Synopsis of the OHS Body Of Knowledge

Background

A defined body of knowledge is required as a basis for professional certification and for

accreditation of education programs giving entry to a profession. The lack of such a body

of knowledge for OHS professionals was identified in reviews of OHS legislation and

OHS education in Australia. After a 2009 scoping study, WorkSafe Victoria provided

funding to support a national project to develop and implement a core body of knowledge

for generalist OHS professionals in Australia.

Development

The process of developing and structuring the main content of this document was managed

by a Technical Panel with representation from Victorian universities that teach OHS and

from the Safety Institute of Australia, which is the main professional body for generalist

OHS professionals in Australia. The Panel developed an initial conceptual framework

which was then amended in accord with feedback received from OHS tertiary-level

educators throughout Australia and the wider OHS profession. Specialist authors were

invited to contribute chapters, which were then subjected to peer review and editing. It is

anticipated that the resultant OHS Body of Knowledge will in future be regularly amended

and updated as people use it and as the evidence base expands.

Conceptual structure

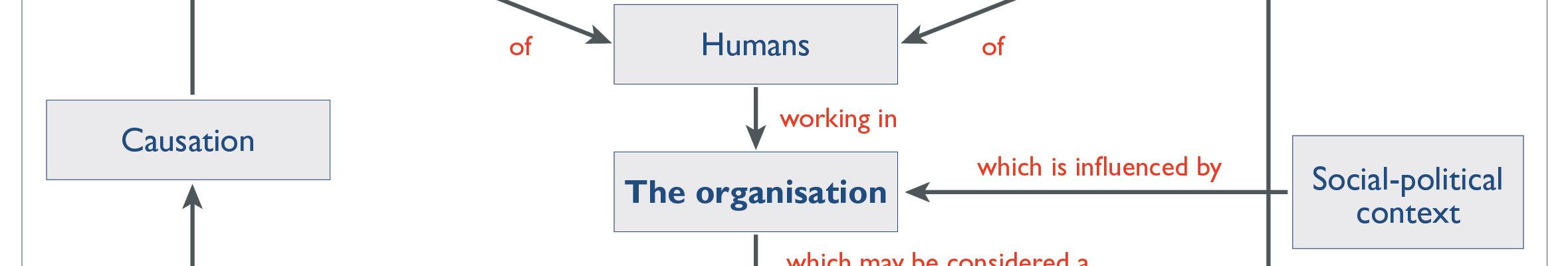

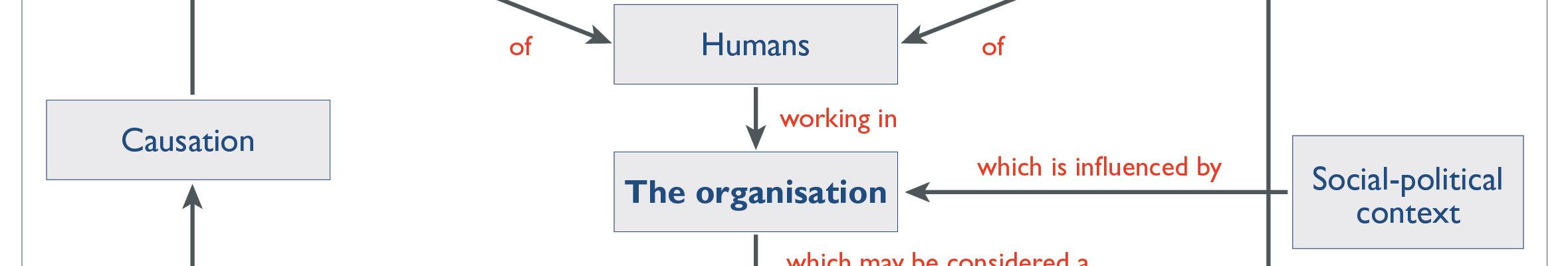

The OHS Body of Knowledge takes a ‘conceptual' approach. As concepts are abstract, the

OHS professional needs to organise the concepts into a framework in order to solve a

problem. The overall framework used to structure the OHS Body of Knowledge is that:

Work impacts on the safety and health of humans who work in organisations. Organisations are

influenced by the socio-political context. Organisations may be considered a system which may

contain hazards which must be under control to minimise risk. This can be achieved by

understanding models causation for safety and for health which will result in improvement in the

safety and health of people at work. The OHS professional applies professional practice to

influence the organisation to being about this improvement.

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

This can be represented as:

Audience

The OHS Body of Knowledge provides a basis for accreditation of OHS professional

education programs and certification of individual OHS professionals. It provides guidance

for OHS educators in course development, and for OHS professionals and professional

bodies in developing continuing professional development activities. Also, OHS

regulators, employers and recruiters may find it useful for benchmarking OHS professional

Application

Importantly, the OHS Body of Knowledge is neither a textbook nor a curriculum; rather it

describes the key concepts, core theories and related evidence that should be shared by

Australian generalist OHS professionals. This knowledge will be gained through a

combination of education and experience.

Accessing and using the OHS Body of Knowledge for generalist OHS professionals

The OHS Body of Knowledge is published electronically. Each chapter can be downloaded

separately. However users are advised to read the Introduction, which provides background

to the information in individual chapters. They should also note the copyright requirements

and the disclaimer before using or acting on the information.

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

Models of Causation: Health Determinants

Wendy Macdonald BSc(Hons)Psych, G.DipPsych, PhD, MHFESA, MICOH, FSIA, FIEA

Associate Professor, Centre for Ergonomics and Human Factors,

Faculty of Health Sciences, La Trobe University

Email: [email protected]

Wendy is a highly experienced OHS educator, researcher and consultant, and a road safety researcher. Her OHS research interests include: workplace management strategies to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries and disorders; impacts of workload on occupational stress and wellbeing; issues related to workforce ageing; and OHS in industrially developing countries. She plays a leading role within the World Health Organisation (WHO) global network of Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health, of which her own Centre is a member. On behalf of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA) she is responsible for liaison between the IEA and the WHO network.

Peer reviewer

Professor Niki Ellis MBBS, AFOEM, AFPHM

Chief Executive Officer

Institute of Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research, Monash University

Core Body of

Knowledge for the

Generalist OHS

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

Core Body of Knowledge for the Generalist OHS Professional

Models of Causation: Health Determinants

Abstract

Health is a state with both negative and positive dimensions; it extends beyond the absence

of diseases and disorders to encompass personal wellbeing more generally. Its

determinants are diverse and not confined to workplace hazard exposures, so identifying

and managing the main work-related influences on health can be difficult. Models of

occupational health causation range from macro-level conceptions, which include

determinants external to the workplace but are insufficiently detailed to guide workplace

risk management, through to evidence-based models depicting the work-related causes of a

particular disease or disorder. An understanding of the latter type of causal model is

particularly important to enable effective risk management of diseases and health disorders

that have multiple and potentially interacting hazards (e.g. musculoskeletal disorders,

mental disorders, cardiovascular diseases).

Keywords

health, illness, disease, causation, work

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

Contents

Historical overview .1

Understanding the determinants of occupational health outcomes .2

‘Causation' and work-relatedness.2

Macro-level models of occupational health determinants .4

Hazard-specific diseases and disorders .6

Diseases and disorders with multiple determinants .7

Workplace benefits and determinants of positive wellbeing . 14

Implications for OHS practice . 19

Management of risk for diseases/disorders with multiple, diverse causes . 19

Management of risk from psychosocial hazards . 20

Workplace health promotion . 20

Professional roles . 21

Key authors and thinkers . 21

Acknowledgement . 22

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation – Health Determinants

The safety aspects of Occupational Health and Safety (OHS), concerned with prevention of

accident-related injuries, are often seen as central to the role of the generalist OHS

professional. However, contemporary OHS professional practice requires at least an equal

focus on workers' health. This chapter – one of two about models of causation1 – describes

the kinds of health-related causal models required for effective OHS risk management.

Section 2 outlines the historical contributions of various professional groups to our

understanding of occupational health determinants. Section 3 discusses the basis for

identifying observed health outcomes as ‘work-related', considers various models of

causation, and outlines the importance of positive dimensions of occupational health and their

determinants. Finally, section 4 summarises implications for OHS professional practice.

Historical overview

The history of occupational health practice dates back several thousand years (see Abrams,

2001; Gochfeld, 2005). This section briefly considers the contributions of various

professional groups to our current understanding of occupational health determinants.

Medical practitioners played a key role during the earliest years, leading during the 20th

century to development of the profession of occupational medicine (Lane & Lee, 1991).

Occupational diseases were initially attributed only to physical hazards, particularly

chemical, physical and biological exposures; the fields of industrial toxicology and

occupational hygiene emerged from this approach. Occupational epidemiology and related

sociological research also developed during the 20th century from origins traceable to the

early 18th century work of Ramazzini (2001 translation), who documented the hazards and

related health problems for more than 50 occupations in De Morbis Artificum Diatriba

(Diseases of Workers).2 More recently, epidemiologists and public health professionals have

elucidated the social determinants of health, both within and external to workplaces; for

example, the now famous WhiteHall Studies were instigated by Marmot during the 1960s and

are ongoing (see Marmot, Siegrist & Theorell, 2006).

Development of sociotechnical systems theory during the 1940s and 50s by psychologists at

the Tavistock Institute in London provided one of the first examples of a systems approach to

optimise both work performance and employee wellbeing (Trist, 1981). Concurrently, the

related field of ergonomics brought a human-centred approach to the workplace, focusing

variously on system safety and performance, and on occupational health issues (Wilson,

2000). The field of occupational health psychology emerged during the 1980s from a

1 See OHS BoK Models of Causation: Safety. 2 For detail on the historical context for occupational health see OHS BoK The Human: As a Biological System. OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

confluence of industrial/organisational psychology and health psychology, with recent inputs

also from psychoneurobiology as it relates to the physiological processes underpinning

psychological wellbeing (for example see Pressman and Cohen, 2005). Professionals in this

field have highlighted the widespread impacts on occupational health of work-related

stressors, and have specialist expertise in managing workplace risks stemming from

psychosocial hazards, particularly as they relate to mental disorders and wellbeing.3

In summary, it can be seen that the field of occupational health now spans highly diverse

areas of expertise. Some implications for OHS professional practice are discussed in section

Understanding the determinants of occupational health outcomes

This section first discusses the nature of ‘causation' within an OHS context and the basis for

concluding that observed health outcomes are work-related. It then discusses the nature and

role of macro-level models of occupational health determinants. The third part identifies the

kinds of diseases/disorders which typically have just one main work-related cause, and the

fourth discusses causal models for diseases/disorders with multiple, possibly interacting

determinants. The final part of this section considers positive dimensions of health and their

determinants, since the importance of these is being increasingly recognised, consistent with

the World Health Organization definition of health as "a state of complete physical, mental

and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" (WHO, 1948).

‘Causation' and work-relatedness

The development and implementation of effective OHS intervention strategies requires an

understanding of the factors ‘causing' occupational health outcomes. In this context, causes

include work-related hazards and other risk factors that increase the probability and/or

severity of harm to health, as well as factors that promote positive states of health and

wellbeing.

Determining the causes of injuries is usually a more straightforward process than diagnosing

the causes of health outcomes. The most obvious reason for this difference is that with

injuries there is usually no separation in time between the injury and the harmful event that is

its immediate cause. For example, in the case of a person's contact with the cutting edge of a

machine blade, the harmful event provides a clear starting point for investigations to

determine causation and the work-relatedness of the injury is not disputed. In contrast, health

3 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

outcomes often result from exposures to hazards4 over extended periods of time, and there

may be latency periods of many decades between the hazard exposure(s) and the

manifestation of health effects. This longer timeframe makes it less likely that the harm to

health will be identified as work-related, and increases the difficulty of identifying relevant

hazards and other risk factors in any individual case.

Work-related injuries can often be attributed to several work-related causal factors, but the

high salience of the injurious event can result in risk management focusing too narrowly on

that event. For example, efforts to control risk of injury from a machine blade often focus on

installation of a well-designed guard, but it might also be important to control factors such as

production pressures that motivate workers to save time by disabling the machine guard,

inadequate supervision, and poor safety culture more generally.5

Work-related health outcomes are different from injury outcomes in that many diseases by

their nature are indicative of their cause, whereas this is not true of injuries. The nature of

injuries suffered in an accident does not usually indicate the cause of the accident; for

example, the causes of road accidents cannot usually be deduced from the nature of injuries

suffered. In contrast, diseases such as mesiothelioma, or disorders such as noise-induced

hearing loss, by their nature indicate the main work-related cause of that health outcome –

exposure to asbestos in the first case and to excessive noise in the second. Causal

mechanisms differ widely between different health outcomes, and because of this diversity, a

variety of quite different causal models are required to support occupational health

Another important difference between causation of injuries and of health outcomes is that the

latter are usually more affected by non-work factors, and the work-relatedness of many health

problems therefore tends to be poorly documented and inadequately acknowledged.

Nevertheless, some diseases have been widely accepted as work-related (i.e. as ‘occupational' diseases) due to their hazard-specific nature and the low probability of non-work exposures to that particular hazard. Examples include diseases arising from exposure to

dust, poisonings from exposures to some hazardous substances, and infections transmitted

from farm animals to farmers, veterinarians or abattoir workers. Although noise-induced

hearing loss is widely accepted as an occupational disorder, the increasing incidence of non-

work exposures due to personal music devices may render this increasingly open to dispute.

In the case of cancers, work-relatedness is often disputed, particularly those that are both very

common and very severe in their effects so there is a lot at stake. Attempts have been made to

determine the overall proportion of cancers that are work-related, but:

4 Exposure may be defined in terms of both its nature and its extent. For the present purpose, nature of exposure refers to the type of hazard to which people are exposed; this encompasses the various types of hazard listed in the OHS BoK. Extent of exposure refers to the severity and duration of the exposure. 5 For conceptual models supporting analysis of the causation of harmful events see OHS BoK Models of Causation: Safety. OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Reliably establishing the causes of any one cancer type is very difficult because cancer proceeds from a combination of events, these events occur over a period of years or decades, and causal factors seldom fingerprint the cancer histology (Benke & Goddard, 2006, p. 485).

For any such health outcomes, a causal relationship, rather than just a statistical association,

is more likely when:

· Exposure precedes the health outcome (essential for causality, but not always easy to

establish, e.g. because cancer might start years before it manifests clinically)

· The observed association is strong · More intense or prolonged exposures are associated with more frequent or severe

outcomes (i.e. there is a dose-response relationship)

· The association between exposure and outcome is compatible with existing

knowledge of biological mechanisms

· A particular kind of exposure tends to be associated with a particular health outcome · Evidence is similar across different groups at different times (Hill, 1965; NRC&IM,

For further discussion of causation in an OHS context, see Hill (1965), or a report by the

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, USA (2001, pp. 65–82).

Macro-level models of occupational health determinants

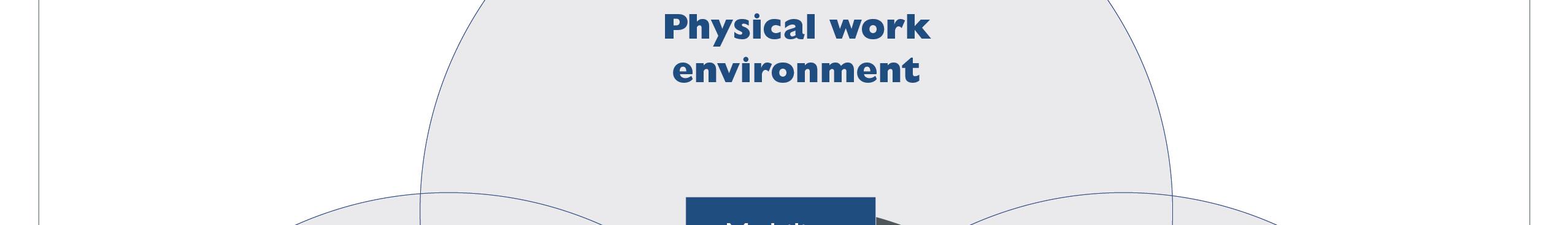

Macro-level models of occupational health determinants provide comprehensive coverage of

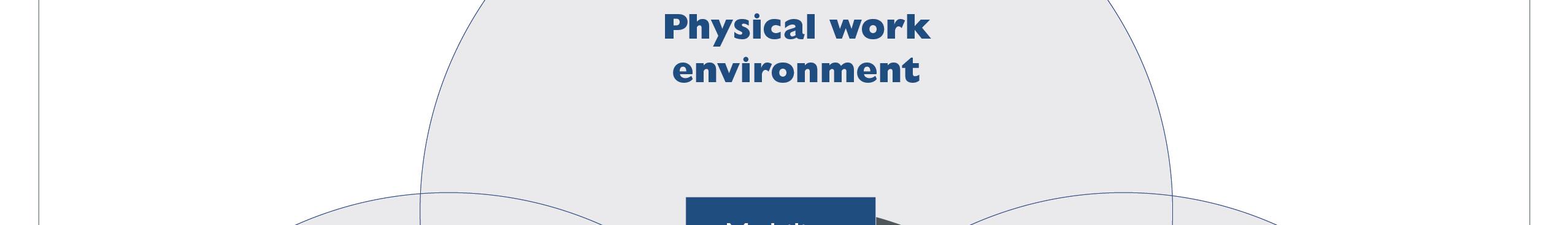

factors including, but not confined to, work-related hazards. A good example of such a model

is the World Health Organization's Healthy Workplace Model (Burton, 2010) (Figure 1).

This depicts the OHS risk-management action cycle (an eight-step continual improvement

process – Mobilize, Assemble, Assess, Prioritize, Plan, Do, Evaluate, Improve) in the context

of four overlapping sets of occupational health determinants: the psychosocial work

environment, the physical work environment, personal health resources, and linkages

between the enterprise and its wider community. Of central importance are the enterprise's

core ethics and values, supported and promoted by leadership engagement and worker

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Figure 1: WHO Healthy Workplace Model: Avenues of Influence, Process and Core

Principles (Based on Burton, 2010, p. 3)

Sorensen et al. (as cited in Ellis)6 conceived an even ‘bigger picture' macro model that

includes four sets of external influences on occupational health that are not depicted in the

WHO model: legal, economic, political and social factors. However, the WHO model

includes more detail at the individual enterprise level.

In common with most macro models of occupational health determinants, Figure 1 includes

an element – ‘personal health resources' – representing relevant characteristics of workers. In

the Sorensen et al. model used by Ellis this is termed ‘individual health-related behaviors'; in

the systems models used by ergonomists such an element typically refers to the capacities and

limitations that affect people's ability to cope with work demands (e.g. see ‘coping resources' 6 OHS BoK Global Concept: Health (section 3) OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

in Figure 4). Thus, although these models differ in the particular individual variables

identified, there is consensus that some individual-level factors should be included in the

overall conceptual framework. Examples of individual variables that may be important in the

occupational health context include:

· Personal vulnerabilities and causal factors stemming from:

o Permanent or stable factors: age, gender, physical size and strength

(anthropometrics), personality characteristics (e.g. positive/negative effect,

locus of control), health-related genetic vulnerabilities and predispositions,

chronic health problems, etc.

o Factors amenable to change within a medium timeframe: work-related

knowledge and skills, health-related behaviours (e.g. nutrition, exercise,

smoking), some health problems and injuries, job satisfaction and morale,

physical fitness, etc.

o More transitory states: fatigue, stress, mood, etc.

· Lifestyle factors (e.g. having to cope with demands from personal commitments to

family and friends; availability of personal support from non-work sources) might

also be relevant in some contexts.

Personal and lifestyle factors such as the above are often seen as exerting a major influence

on health. For example, even when someone suffers a ‘heart attack' at work, the causes are

more likely to be seen as personal and lifestyle rather than work-related factors (despite the

evidence on work-related causes of cardiovascular disease discussed in section 3.3 below). In

contrast, when someone suffers injury due to an accident at work, it is usual to look for work-

related causes, even when personal factors are also identified as contributors.

Macro-level models illustrate the wide range of both work and non-work factors that

influence occupational health. They span public health as well as occupational health

domains, providing the basis for a broad range of health protection and promotion strategies

both within and beyond the workplace. However, more narrowly focused causal models are

required to guide the detailed development of risk-management strategies at the workplace

Hazard-specific diseases and disorders

Some occupational diseases and disorders are associated with one primary work-related

hazard as opposed to a diverse range of hazards of varying importance.7 Examples of hazard-

specific health conditions are shown in Table 1, with the hazard of primary importance

shown in the right-hand column. Effects of exposures to the primary work-related hazard

7 Because of their strong association with a particular hazard, further information about the causation of such diseases or disorders is located in the relevant OHS BoK Hazard chapters. OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

(plus exposures external to the workplace) interact with individual susceptibilities to increase

risk of the particular disease or disorder.

Table 1: Causal factors for a sample of diseases/disorders where there is one main

work-related hazard

Example of

Individual susceptibility

Work-related hazards –

Inherent

Acquired

causal agent(s)

· Some substance

· Excessive noise levels

hearing loss

exposures (prescribed, occupational)

· Asbestos dust

unknown, but a genetic influence is likely

· Contact with infected

· Coxiel a burneti (bacterium)

Allergic contact · Inherited or early · Continuing exposure to · e.g. nickel, chromium, epoxy dermatitis

sensitising agent

resins, latex particles,

· Co-existing irritant

· Inherited or early · Prior exposure to

· e.g. volatile isocyanates,

sensitising agent

protein dusts, Western Red

· Hyper-reactivity of the

Cedar, aluminium smelting

individual's airways

Diseases and disorders with multiple determinants

Ellis noted that "The traditional OHS model is straining as the burden of health in workplaces

shifts to illness arising from chronic disease."8 This situation is primarily due to

diseases/disorders that typically have multiple causes. These include cardiovascular diseases,

musculoskeletal disorders and mental disorders, which are three of the eight

diseases/disorders identified as warranting particular focus within Australia's National OHS Strategy 2002–2012 (Safe Work Australia, 2010a).

In 2010, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported:

More than 6.1 million Australians aged 16–85 years suffer from a musculoskeletal condition at a point in time (38% of that population) and 3.2 million (20%) experience a mental disorder in a 12–month period (AIHW, 2010, p. 1).

Such evidence illustrates that both musculoskeletal and mental disorders have major impacts

on population health, beyond their more easily quantifiable costs in terms of compensation

claims. Australian workers' compensation statistics for the period 2007–08 showed that

8 OHS BoK Global Concept: Health (Abstract) OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

musculoskeletal injuries and disorders were responsible for the largest proportion of serious

claims,9 followed by mental disorders.

The most common injury leading to serious claims was Sprains & strains of joints & adjacent muscles, which accounted for 43% of all serious claims. The most common diseases resulting in serious claims were Disorders of muscle, tendons & other soft tissues (6% of all serious claims), Dorsopathies – disorders of spinal vertebrae (6% of all serious claims) and Mental disorders (5% of all serious claims). (Safe Work Australia, 2010b, p. vii)

These compensation statistics create the impression that sudden-onset musculoskeletal injuries (sprains and strains) are much more common than cumulative disorders, in which case consideration of their determinants would be outside the scope of this chapter focussed

on health determinants. However, many musculoskeletal problems cannot be clearly

diagnosed as either an ‘injury' or a ‘disease/disorder' (ASCC, 2006), since it is now evident

that thresholds for acute injury are reduced by cumulative exposures, both within a work shift

and over longer time periods (e.g. Visser & van Dieen, 2006; van Dieen, 2007). The

dichotomy between acute and cumulative injury is even more questionable when information

about causation is derived from compensation claims data. Several factors combine to make it

likely that compensation claims focus largely on events immediately preceding the report,

resulting in substantial bias towards reporting an injury rather than a disease (see Macdonald

& Evans, 2006, pp. 12–15). In any case, body stressing is the reported mechanism for all

such claims categorised as diseases and most of those categorised as injuries; overall, body

stressing is the reported mechanism in 41% of all serious claims (including both injuries and

disorders). Consequently, causal models for cumulative onset musculoskeletal disorders

encompass most of the important work-related hazards for musculoskeletal injuries also

(ASCC, 2006). Risk factors specific to sprain/strain injuries where the mechanism is

falls/slips/trips are considered elsewhere.10

As noted above, mental disorders constitute the second largest category of serious claims,

following musculoskeletal disorders (Safe Work Australia, 2010c). Importantly, there is a

statistical association between these two categories of disorder:

Published studies suggest that causal pathways are more likely to be from musculoskeletal conditions to mental disorders than the reverse, although the latter can also occur…The clear association between musculoskeletal conditions and mental disorders found in this study emphasises the need for health-care providers to be aware of and provide for a multidisciplinary approach to the management of this comorbidity. (AIHW, 2010, p. 2)

Since psychosocial hazards are the primary work-related cause of mental disorders, the nature

and causation of mental disorders is the chapter on that type of hazard, by Way11.

9 "Serious claims are those lodged in the reference year and accepted by the date at which the data are extracted and involve either a death, a permanent incapacity, or a temporary incapacity requiring an absence from work of one working week or more" (Safe Work Australia, 2010b, p. 1). 10 See OHS BoK Gravitational Hazards 11 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

The third category of disease/disorder considered here is cardiovascular. Cardiovascular

diseases are not responsible for a large proportion of compensation claims in Australia

(where they are termed ‘diseases of the circulatory system') – probably because they have

multiple causal factors unrelated to work and it is difficult to determine the contribution of

work-related hazards in individual cases since they are often asymptomatic until well

advanced. However, there is substantial research evidence that a wide range of work-related

factors – both physical and psychosocial – can contribute to risk of these diseases (Driscoll,

2006; Kim & Kang, 2010; LaMontagna et al., 2006; Landsbergis et al., 2001). According to a

2006 review for the Australian Safety and Compensation Council:

The evidence is strongest with exposure to four particular chemicals, namely carbon disulphide and, in terms of acute exposure, carbon monoxide, methylene chloride and nitroglycerin. There is also good evidence for the role of environmental tobacco smoke and psychosocial factors, particularly low job control, and considerable evidence for noise and shiftwork. Other exposures, for which the evidence is less strong, include chronic low-level exposure to carbon monoxide, methylene chloride and nitroglycerin, other chemicals, long working hours, electromagnetic fields, temperature extremes, diesel exhaust and other particulates, organic combustion products, manual work or strenuous occupations, sedentary work, and certain specific occupations. (Driscoll, 2006, pp. vi–vii)

Other reviews have placed greater emphasis on the causal role of work-related psychosocial

hazards (e.g. see LaMontagna et al., 2006, 2007). The importance of such factors was

emphasised in a report from Korea's Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (Kim

& Kang, 2010), which found that the "triggering factors" in cases of cerebrovascular diseases

(n = 211) were job stress (20.9%), overload (32.7%), shift and night work (3.3%),

professional driving (2.4%), environmental change (1.4%), others (7.1%) and unknown

(32.2%). In cases of coronary heart disease (n = 117), the triggering factors were job stress

(22.2%), overload (44.4%), shift and night work (3.5%), professional driving (0.9%),

environmental change (0.9%), others (8.5%) and unknown (19.7%).

Where a large array of factors coalesces to produce an outcome, as for the above types of

diseases/disorders, the processes involved can be depicted in a model of causation.12 For

diseases and disorders where risk typically arises from a multiplicity of hazards, there are

models depicting the aetiology of each particular disease/disorder in terms of how exposures

to various hazards combine with other risk factors in determining risk level. To illustrate this,

the following section considers models of causation for musculoskeletal disorders.

12 See also OHS BoK Models of Causation: Safety OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

3.4.1 An example: Models of causation for musculoskeletal disorders13

For health or safety outcomes arising primarily from just one type of hazard, risk can be

estimated in terms of the severity of the hazard and the extent of exposure to it. However, for

multi-hazard conditions such as musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), risk depends on the

particular combination of hazards present. It has been shown that interactions between a

number of hazards and related factors can substantially affect MSD risk (Bernard, 1997;

Marras, 2008; NRC&IM, 2001), which means that the extent of a particular exposure, if

considered independently of other exposures, is not necessarily a good indicator of MSD risk.

Importantly, this means that MSD risk cannot be adequately assessed by separately

evaluating each potential hazard or risk factor, as is typical for hazard-focused risk

assessment. This point is discussed further below, with reference to hazards depicted in

Figures 2 to 4 show evidence-based models of MSD causation, illustrating the diverse array

of hazards that can affect MSD risk.

13 "Musculoskeletal disorders include a wide range of inflammatory and degenerative conditions affecting the muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, peripheral nerves, and supporting blood vessels.[They include] over 100 diseases and syndromes, which are usually progressive and are associated with pain.such as ‘repetitive strain injuries', ‘occupational overuse syndrome', ‘back injury', ‘osteoarthritis', ‘backache', ‘sciatica', ‘slipped disc', ‘carpal tunnel syndrome' and others. [They] exert a substantial economic burden in health care and compensation costs, lost salaries and productivity borne not only by the employers and employees, but also by the community. As the conditions become more serious and impinge on the person's functional capacity, their work performance and productivity are also likely to decrease." (ASCC, 2006, pp. 9–10) OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Figure 2: Model of hazards and other risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal

disorders (based on NRC&IM, 2001, p. 3)

The model in Figure 2 resulted from a review of research evidence by a multidisciplinary

committee of experts on behalf of the USA National Research Council and Institute of

Medicine (2001). On the left side of the model within The Workplace there are three groups

of hazards and risk factors: ‘external loads' (biomechanical hazards),14 ‘organisational

factors', and ‘social context'; those in the latter two groups are commonly known as

psychosocial hazards.15 Hazards within all three categories interact (shown by linking arrows)

and can affect processes internal to The Person (internal biomechanical loading,16

physiological responses) and personal outcomes (discomfort, pain, impairment, disability).

Also, fatigue is recognised as a relevant factor.17 As shown on the right of the diagram,

individual factors influence all personal processes and outcomes.

Although stress is not highlighted in Figure 2, it is implicit there within ‘physiological

14 See OHS BoK Biomechanical Hazards 15 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress 16 Different from the external biomechanical loading discussed in OHS BoK Biomechanical Hazards 17 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards: Fatigue OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

responses'. The well-documented role of stress in MSD causation is much more apparent in

Figure 3, which highlights the interacting effects of physical (mainly biomechanical) and

psychosocial hazards on MSD risk. A person's internal ‘stress response,' as shown here,

occurs when situations are experienced as stressful; it is multidimensional, with physiological

and behavioural, as well as cognitive and affective dimensions (Cox, 1978). The cognitive

and behavioural aspects of this response can directly affect safety, while the physiological

and affective aspects can have profound effects on health including, but not confined to,

MSD risk18 (e.g. Aptel & Cnockaert, 2002; Chandola et al., 2008; Macdonald & Evans, 2006;

Figure 3: A model highlighting evidence that internal processes producing cumulative

tissue damage include the multidimensional ‘stress response' as well as internal

biomechanical loads and pain sensitisation (Macdonald & Evans, 2006, p. 10)

18 See OHS BoK The Human: Basic Principles of Psychology OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Figure 4: A composite ergonomics model of work-related hazards for musculoskeletal

disorders (based on Macdonald & Evans, 2006, p. 24)

The primary purpose of the models in Figures 2 and 3 is to promote better understanding of

MSD aetiology, based on current research evidence. The model in Figure 4 is in accord with

these, but is more directly applicable to workplace risk management because it provides more

detail concerning the wide range of work-related hazards that can combine to affect risk. This

model shows that MSD risk is increased if ‘job and task demands' are hazardous or excessive

in relation to available ‘coping resources,' and that risk is also affected by ‘other

psychosocial hazards.' Job and task demands include the widely recognised hazards of

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

manual task performance, along with two other subsets – those arising from the cognitive and

emotional demands of task performance, and those arising from demands of the overall job. Coping resources are determined by workplace factors (support systems and resources; psychosocial and physical environment influences) and by the individual's own capabilities.

Importantly, it is the combination of these diverse variables that determines risk, which is

why MSD risk cannot be adequately assessed by a process that considers each hazard

separately. For example, a particular posture might be rated as low risk if considered alone,

but for workers who are chronically fatigued and/or stressed due to long working hours, tight

production schedules with few rest breaks, and supervisors perceived as unsupportive, the

risk might be considerably higher.

Figure 4 shows various pathways leading from ‘Hazardous workplace and personal

conditions' to the occurrence of musculoskeletal injuries and disorders. In the case of sudden

onset sprains and strains (which are classified as injuries rather than diseases/disorders), there

is a direct link from excessive force and/or adverse posture to injury. However, our focus

here is on the aetiology of cumulative disorders, and for these, the pathway to injury is via

ongoing ‘hazardous personal states' where risk is increased by the kind of internal

physiological and biomechanical processes indicated in Figure 2 and detailed in Figure 3.

The above models (Figures 2–4) clearly show that managing ‘manual handling' hazards is not synonymous with managing MSD risk. In light of this, it is unfortunate that MSDs are often referred to in Australia as ‘manual handling injuries', since that terminology supports

the erroneous assumption that biomechanical hazards are the only important cause of

musculoskeletal problems. Clearly, a much wider range of hazards and risk factors including

some related to work organisation, job design and the workplace environment (psychosocial

as well as physical) must be managed. In particular, it is important to include management of

fatigue and stress, since internal physiological and biomechanical dimensions of these are

linked to MSD risk.

As outlined above, MSD risk management requires a holistic multidimensional approach that

is founded on evidence-based models of causation and takes account of the particular combination of hazards present in a given situation. Further, there is evidence that:

…a combination of several kinds of interventions (multidisciplinary approach) including organisational, technical and personal/individual measures is better than single measures.[and that] a participative approach which includes the workers in the process of change has a positive effect on the success of an intervention (EASHW, 2008, pp. 7–8).

Workplace benefits and determinants of positive wellbeing

The focus of conventional OHS practice has been to prevent harm to workers as reflected in

the disease/disorder causal models reviewed in section 3.4. However, there is increasing

recognition of the importance of achieving good health and wellbeing rather than just

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

avoiding disease. This section considers the workplace benefits of good health and wellbeing,

including their potential role in decreasing occupational disease risk. It finishes with an

outline of key workplace determinants.

Various notions of wellbeing (e.g. happiness and wellness, and more work-specific concepts

such as morale and job satisfaction) have been developed by researchers and applied in

workplace settings. Concepts vary according to whether they concern fairly stable individual

personality dimensions or ‘traits,' or more transient ‘states.' In an OHS context, personal

states are of primary interest as these are most affected by workplace and job conditions.

Such concepts also vary according to their emphasis on affective versus cognitive

dimensions. For example, ‘job satisfaction' is cognitively oriented because it implies some

personal evaluation of the job, although it is also influenced by people's enjoyment of their

job so it has an affective dimension also. ‘Morale' signifies a positive affective state oriented

towards engagement with and commitment to job performance; it is linked to concepts such

as ‘vitality' and ‘vigour' (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Hart and Cooper (2001) identified three

dimensions of occupational wellbeing: morale (positive affect), psychological distress

(negative affect), and job satisfaction (conceived as predominantly cognitive). Warr

(2007a,b) also distinguished three dimensions within wellbeing, which he now refers to as ‘happiness'.

A principal axis runs from feeling bad to feeling good, and two others (distinguished in terms of degree of activation as well as pleasure) extend from negative feelings of anxiety to experiences of happiness as tranquil contentment, and from states of depression to happiness as energised pleasure (Warr, 2007b, p. 726).

Good health and wellbeing clearly have intrinsic value, particularly to the individuals

concerned. From an employer perspective, high vitality and morale also are beneficial

because of their links to good work performance. Importantly in this OHS context, high

levels of job satisfaction have been linked to lower duration of sickness absence (Marmot et

al., 1995). Wegge, Schmidt, Parkes and van Dick (2007) concluded that the frequency of

people ‘taking a sickie' and the time lost due to these absences are affected by an interaction

between job satisfaction and job involvement,19 such that high job satisfaction greatly

decreases the negative impact on sickness absence of low job involvement. In other words,

low levels of psychological wellbeing are manifest in various ‘illness behaviours',20 including

more frequent and longer sickness absence. Such absences could therefore serve as one

19 ‘Job involvement' refers to the extent to which an individual identifies with the job. 20 According to Mechanic (1986, p. 1): "Illness behaviour.involves the manner in which individuals monitor their bodies, define and interpret their symptoms, take remedial action, and utilize sources of help.It also is concerned with how people monitor and respond to symptoms and symptom change over the course of an illness and how this affects behaviour, remedial actions taken, and response to treatment. The different perceptions, evaluations and responses to illness have, at times, a dramatic impact on the extent to which symptoms interfere with usual life routines, chronicity, attainment of appropriate care and cooperation of the patient in treatment. Variables affecting illness behaviour usually come into play well before any medical scrutiny and treatment."

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

indicator of the success or otherwise of OHS risk management.

Looking beyond absenteeism to sickness itself, it is well established that negative states such

as stress are linked to poor health.21 Is there also evidence that positive states are beneficial to

health? Based on a large meta-analysis of research reporting associations between job

satisfaction and various measures of health, Faragher, Cass and Cooper (2005) found that

high job satisfaction was strongly associated with good mental health (correlations with

burnout, self-esteem, depression, and anxiety ranged from 0.478 to 0.420). Correlations

between job satisfaction and physical health were smaller, but still highly significant

statistically. The authors concluded that:

The wellbeing of employees—and in particular their mental health—may be compromised if their work is causing them to experience high levels of dissatisfaction. Thus, the extent to which individuals feel satisfied with their work becomes an important (mental) health issue. (Faragher, Cass & Cooper, 2005, p. 111)

Pressman and Cohen (2005) analysed evidence concerning the role of positive affect in the

aetiology of physical diseases and disorders. Their review included research on the

functioning of the cardiovascular, endocrine and immune systems – systems that appear to

mediate the effects of positive affect on health as reported above. They concluded that

positive affect can reduce disease risk via multiple pathways, shown in Figure 5.

21 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

ANS = autonomic nervous system HPA = hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

Figure 5: A ‘stress buffering' model of behavioural and biological mechanisms by which

positive emotions can reduce disease risk (Pressman & Cohen, 2005, p. 959)

Figure 6 presents a simple model of health, its determinants and its OHS impacts. Various

types of work and non-work environmental factors are depicted as influencing health, along

with individual factors, which reflects the more detailed causal models presented above.

Health itself is enclosed within the blue rectangle; it can be seen that this encompasses both

positive and negative personal states, consistent with the widely accepted WHO definition of

health (WHO, 1948). However, these personal states are also among the determinants of

diseases and disorders, which are also part of ‘health'; that is, some aspects of ‘health' (these

personal states) are shown to be determinants of some other aspects of health

(diseases/disorders).

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Figure 6: A model of health, its various work-related and other determinants, and OHS

impacts.

Figure 6 also identifies some determinants of sickness absence. Such absences may be due to

particular diseases and disorders, some of which are work-related, and/or they may be a

manifestation of illness behaviours linked to states such as low morale and high stress, as

discussed above.22 Distinguishing absence from work due to a specific disease/disorder from

absence representing illness behaviour is particularly difficult in the case of both

musculoskeletal and mental disorders (Australia's two largest ‘occupational disease'

compensation claims categories). In both these types of disorder, the influence of personal

states as depicted in Figure 6 can be centrally important; consequently, an understanding of

how best to manage these personal states is important for OHS professionals.

What then are the main work-related determinants of these personal states, which can

influence health both positively and negatively? Causes of stress and fatigue are considered

elsewhere.23 What about the determinants of positive states such as morale and job

22 Ellis has highlighted the potential importance of illness behaviours, pointing out: "An underlying disease can be detected in only about half of presentations to general practitioners" (OHS BoK Global Concept: Health, section 2.3). 23 OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress; OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards: Fatigue. OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

satisfaction? Warr (2007b) concluded that the main workplace determinants of wellbeing, or

· Opportunity for personal control – discretion, decision latitude, participation, etc. · Opportunity for skill use and acquisition – a setting's potential for applying and

developing expertise and knowledge

· Externally generated goals – ranging across job demands, underload and overload,

task identity, role conflict, required emotional labour and work-home conflict

· Variety – in job content and location · Environmental clarity – including role clarity, task feedback and low future ambiguity · Contact with others –both quantity and quality · Availability of money – the opportunity to receive income at a certain level · Physical security – including working conditions, degree of hazard, etc. · Valued social position – in terms of the significance of a task or role · Supportive supervision – the extent to which one's concerns are taken into

· Career outlook – encompassing job security and the opportunity to gain promotion or

shift to other roles

· Equity – both within the organisation and in that organisation's relations with society

(Warr, 2007b, p. 727).

Comparison of the above factors with those identified as psychosocial hazards or stressors24

shows a high degree of overlap, but the importance of each factor as a determinant of

wellbeing is likely to vary depending on the particular context and the state or aspect of

wellbeing that is of interest.

Implications for OHS practice

Management of risk for diseases/disorders with multiple, diverse causes

The conventional approach to OHS risk management has been to focus on hazard

management – identifying hazards, assessing risk from each identified hazard, and taking any

necessary steps to control risk from each hazard separately. For health-related risks, this

approach works well for hazard-specific diseases and disorders of the kind discussed in

However, a more holistic approach to risk management is required to achieve effective

control of risk for diseases and disorders for which risk is determined by multiple, diverse

hazards, such as musculoskeletal disorders and mental disorders. To manage such health risks

effectively, the management process needs to be guided by an appropriate model of

24 See OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress. OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

causation. Such models identify the multiple causal pathways between the relevant set of

hazards and the particular type of health outcome, so that risk management can be based on

assessment of risk from the combined effects of the hazards identified as most relevant in the

particular situation, taking account of the hazards' additive and possibly interacting effects.

Worker participation in this holistic approach to risk management is likely to be beneficial, if

Management of risk from psychosocial hazards

Occupational health is of course influenced by the presence or absence of diseases and

disorders. Health is also directly influenced by psychological states such as stress, ‘vitality'

and morale (shown in Figure 6), which in turn are influenced by a wide range of work-related

psychosocial hazards. It is therefore essential that OHS risk management deals effectively

with risk from this kind of hazard. The importance of this is particularly clear in countries

such as Australia, where the most expensive compensation claims are for diseases/disorders

where risk is strongly influenced by psychosocial hazards. A participative, holistic approach

is required to manage risk from psychosocial hazards and to promote positive aspects of

health and wellbeing.25

Workplace health promotion

Ellis (2001) proposed a model of OHS risk management that encompasses health promotion

as well as harm prevention. Based on current knowledge of the occupational health benefits

of positive psychological states and the increasing importance of a sustainably healthy

workforce in the context of population ageing, there are strong argument for incorporating

health promotion strategies within OHS risk management programs. This viewpoint is

evident in the WHO Healthy Workplace Model (Figure 1).

The concept of health promotion originated in the public health domain, and workplace

health promotion strategies are sometimes simply public health promotion strategies

implemented within a workplace setting (e.g. WHO, 2011). However, boundaries between

occupational and public health are becoming increasingly blurred due to changes in the way

we work,26 and there is:

.a growing appreciation that there are multiple determinants of workers' health.[and] workforce health promotion initiatives have moved toward a more comprehensive approach, which acknowledges the combined influence of personal, environmental, organizational, community and societal factors on employee well-being (WHO, 2011).

25 OHS BoK Psychosocial Hazards and Occupational Stress. 26 See OHS BoK Global Concept: Work OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Professional roles

The body of scientific evidence concerning the nature and determinants of occupational

health spans a wide variety of disciplines, as outlined in section 2. This diversity is reflected

in the fragmented nature of current OHS professional practice, where specialist groups

include occupational hygienists, occupational ergonomists, occupational physicians,

occupational health nurses, occupational health psychologists, occupational rehabilitation

professionals, and so on. Consequently, the task of defining a core body of occupational

health knowledge and associated professional competencies for generalist OHS professionals

presents a considerable challenge.

In light of the major differences in causation between different types of diseases/disorders, no

OHS professional can be expected to have a high level of expertise in managing all types of

risk to occupational health. Indeed, it seems likely that most generalist OHS professionals

will have some degree of specialist expertise also, probably reflecting existing areas of

specialist OHS professional practice. In this situation there are likely to be ongoing ethical

dilemmas and debate concerning what constitutes an adequate level of competence or

expertise for a particular work role.

Arguably the most important element of professional competency might be a good

understanding of the limitations of one's own knowledge and competencies. This will only be

achievable if generalist OHS professionals are familiar with a comprehensive range of causal

models of occupational health determinants relevant to their field of practice. On this basis

they will be able to analyse and understand a particular problem or situation sufficiently to

recognise if/when they need to enlist specialist support, consistent with the model of

professional practice.27

This chapter has described models of occupational health determinants and their roles in

supporting effective OHS risk management. An understanding of such models was shown to

be particularly important for the effective management of diseases/disorders where risk is

affected by multiple hazards, some of which can interact. Such health conditions include

musculoskeletal disorders, mental disorders, and cardiovascular disease. The importance of

positive wellbeing for occupational health was also described.

Key authors and thinkers

Tom Cox, Austin Bradford Hill, Michael Marmot, William Marras, Bernadino Ramazzini,

27 See OHS BoK Model of OHS Practice OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Thanks to Dr David Goddard, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine,

Monash University, for his invaluable contributions to this chapter.

References

Abrams, H. K. (2001). A short history of occupational health. Journal of Public Health

Policy, 22(1), 34–80.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (2010). When musculoskeletal

conditions and mental disorders occur together. AIHW Bulletin, 80 (Cat. no. AUS 129). Canberra, ACT: AIHW. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468392

Aptel, M., & Cnockaert, J. C. (2002). Stress and work-related musculoskeletal disorders of

the upper extremities. Trade Union Technical Bureau (TUTB) Newsletter, 19–20, 50–56. Retrieved May 2011 from http://hesa.etui-rehs.org/uk/newsletter/files/Newsletter-20.pdf

ASCC (Australian Safety and Compensation Council). (2006). Work-related Musculoskeletal

Disease in Australia. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/AboutSafeWorkAustralia/WhatWeDo/Publications/Documents/119/WorkRelatedMusculoskeltalDisorders_2006Australia_2006_ArchivePDF.pdf

Benke, G., & Goddard, D. (2006). Estimation of occupational cancer in Australia still needs

local exposure data. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 30(5), 485–486.

Bernard, B. P. (Ed.). (1997). Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and workplace factors.

Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Burton, J. (2010). WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and

Supporting Literature and Practice. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf

Chandola, T., Britton, A., Brunner, E., Hemingway, H., Malik, M., Kumari, M., Badrick, E.,

Kivimaki, M., & Marmot, M. (2008). Work stress and coronary heart disease: What are the mechanisms? European Heart Journal, 29(5), 640–648.

Cox, T. (1978). Stress. London: Macmillan.

Driscoll, T. (2006). Work-related Cardio-vascular Disease in Australia Canberra, ACT:

Australian Safety and Compensation Council. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/AboutSafeWorkAustralia/WhatWeDo/Publications/Documents/116/WorkRelatedCardiovascularDisease_2006Australia_2006_ArchivePDF.pdf

EASHW (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work). (2008). Work-related

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Musculoskeletal Disorders: Prevention Report. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, EASHW. Retrieved May 2011 from http://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/reports/en_TE8107132ENC.pdf

Ellis, N. (2001). Work and health: Management in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne,

VIC: Oxford University Press.

Faragher, E. B., Cass, M., & Cooper, C. L. (2005). The relationship between job satisfaction

and health: A meta-analysis. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112.

Gochfeld, M. (2005). Chronologic history of occupational medicine. Journal of Occupational

& Environmental Medicine, 47(2), 96–114.

Hart, P. M., & Cooper, C. L. (2001). Occupational stress: Toward a more integrated

framework. In N. Anderson, D. S. Ones, H. K. Sinangil & C. Viswesvaran (Eds.), Handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology, Volume 2, organizational psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 93–114). London, UK: Sage.

Hill, A. B. (1965). The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings of

the Royal Society of Medicine, 58, 295–300.

Kim, D-S., & Kang, S-K. (2010). Work-related cerebro-cardiovascular diseases in Korea.

Journal of Korean Medical Science, 25(Suppl.), S105–S111.

LaMontagne, A. D., Keegel, T., Louie, A. M., Ostry, A., & Landsbergis, P. A. (2007). A

systematic review of the job-stress intervention evaluation literature, 1990–2005. International Journal of Occupational & Environmental Health, 13(3), 268–280.

LaMontagne, A. D., Louie, A., Keegel, T., Ostry, A., & Shaw, A. (2006). Workplace Stress

in Victoria: Developing a Systems Approach (Report to the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation). Carlton South, VIC: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/workplacestress

Landsbergis, P. A., Schnall, P. L., Belkic, K. L., Baker, D., Schwartz, J., & Pickering, T. G.

(2001). Work stressors and cardiovascular disease. Work, 17(3), 191–208.

Lane, R. E., & Lee, W. R. (1991). The development of training in occupational medicine in

the United Kingdom. Environmental & Occupational Health, 19(2), 247–255.

Macdonald, W., & Evans, O. (2006). Research on the Prevention of Work-related

Musculoskeletal Disorders. Stage 1 – Literature Review. Canberra, ACT: Australian Safety & Compensation Council,. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/ABOUTSAFEWORKAUSTRALIA/WHATWEDO/PUBLICATIONS/Pages/RR200606ResearchOnPreventionOfWRMusculoskeletalDisorders.aspx

Marmot, M., Feeney, A., Shipley, M., North, F., & Syme, S. L. (1995). Sickness absence as a

measure of health status and functioning: From the UK Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 49(2), 124–130.

Marmot, M., Siegrist J., & Theorell, T. (2006). Health and the psychosocial environment at

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

work. In M. Marmot & R. G. Wilkinson (Eds.), Social determinants of health (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marras, W. S. (2008). The working back: A systems view. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mechanic, D. (1986). The concept of illness behaviour: Culture, situation, and personal

predisposition. Psychological Medicine, 16(1), 1–7.

NRC&IM (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine). (2001). Musculoskeletal

disorders and the workplace: Low back and upper extremities (Methodological issues and approaches, pp. 65–81). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10032&page=R2

Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological

Bulletin, 131(6), 925–971.

Ramazzini, B. (2001). De morbis artificum diatriba [Diseases of workers]. American Journal

of Public Health, 91(9), 1380–1382.

Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. M. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective

vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65(3), 529–565.

Safe Work Australia. (2010a). National OHS Strategy 2001–2012. Canberra, ACT:

Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/AboutSafeWorkAustralia/WhatWeDo/Publications/Documents/230/NationalOHSStrategy_2002-2012.pdf

Safe Work Australia. (2010b). Compendium of Workers' Compensation Statistics Australia

2007–08. Barton, ACT: Safe Work Australia.

Safe Work Australia. (2010c). Occupational Disease Indicators 2010. Barton, ACT:

Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved May 2011 from http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/ABOUTSAFEWORKAUSTRALIA/WHATWEDO/PUBLICATIONS/Pages/RP201005OccupationalDiseaseIndicators2010.aspx

Trist, E. (1981). Occasional Paper 2: The evolution of socio-technical systems: A conceptual

framework and an action research project Ontario Ontario Ministry of Labour

van Dieen, J. H. (2007). Injury models in observational and experimental research. (Keynote

presentation) In Proceedings of the Sixth International Scientific Conference on Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: PREMUS 2007. Boston, USA.

Visser, B., & van Dieen, J. H. (2006). Pathophysiology of upper extremity muscle disorders.

Journal of Electromyography & Kinesiology, 16(1), 1–16.

Warr, P. (2007a). Work, happiness, and unhappiness. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Warr, P. (2007b). Searching for happiness at work. Psychologist, 20(12), 726–729.

Warren, N. (2001). Work stress and musculoskeletal disorder etiology: The relative roles of

psychosocial and physical risk factors. Work, 17(3), 221–234.

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Wegge, J., Schmidt, K-H., Parkes, C., & van Dick, R. (2007). ‘Taking a sickie': Job

satisfaction and job involvement as interactive predictors of absenteeism in a public organization. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 80(1), 77–89.

Wilson, J.R. (2000). Fundamentals of ergonomics in theory and practice. Applied

Ergonomics, 31, 557-567.

WHO (World Health Organization). (1948). Constitution of the World Health Organization.

Retrieved March 10, 2011, from http://www.who.int/governance/eb/constitution/en/index.html

WHO (World Health Organization). (2011). Workplace health promotion. Retrieved May

2011 from http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/workplace/en/

OHS Body of Knowledge

Models of Causation - Health Determinants

Source: http://www.ohsbok.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/33-Models-of-causation-Health-determinants.pdf

Hindawi Publishing CorporationBioMed Research InternationalVolume 2014, Article ID 121396, 7 pages Clinical StudyAlga Ecklonia bicyclis, Tribulus terrestris, and GlucosamineOligosaccharide Improve Erectile Function, Sexual Quality ofLife, and Ejaculation Function in Patients with ModerateMild-Moderate Erectile Dysfunction: A Prospective,Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Single-Blinded Study

NATIONAL LIFE SCIENCES P2 VERSION 1 (NEW CONTENT) FOR FULL-TIME CANDIDATES NOVEMBER 2011 MARKS: 150 This memorandum consists of 11 pages. Copyright reserved Please turn over Life Sciences/P2 (Version 1) (Full-time) DBE/November 2011 NSC – Memorandum PRINCIPLES RELATED TO MARKING LIFE SCIENCES 2011