Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Patient-reported quality indicators for osteoarthritis: a patient and public generated self-report measure for primary care

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5 DOI 10.1186/s40900-016-0019-x

Patient-reported quality indicators forosteoarthritis: a patient and publicgenerated self-report measure for primarycare

Steven Blackburn1*, Adele Higginbottom1, Robert Taylor2, Jo Bird2, Nina Østerås3, Kåre Birger Hagen3,John J. Edwards1, Kelvin P. Jordan1, Clare Jinks1 and Krysia Dziedzic1

* Correspondence:

Plain English summary:

1Arthritis Research UK Primary Care

People with osteoarthritis desire high quality care, support and information.

Centre, Research Institute for

However, the quality of care for people with OA in general practice is not routinely

Primary Care & Health Sciences,

collected. Quality Indicators can be used to benefit patients by measuring whether

Keele University, Keele, UKFull list of author information is

minimum standards of quality care are being met from a patient perspective.

available at the end of the article

The aim of this study was to describe how a Research User Group (RUG) workedalongside researchers to co-produce a set of self-reported quality indicators forpeople with osteoarthritis when visiting their general practitioner or practice nurse(primary care). These were required in the MOSAICS study, which developed andevaluated a new model of supported self-management of OA to implement theNICE quality standards for OA.

This article describes the public involvement in the MOSAICS study. This was 1) theco-development by RUG members and researchers of an Osteoarthritis QualityIndicators United Kingdom (OA QI (UK)) questionnaire for use in primary care, and 2)the comparison of the OA QI (UK) with a similar questionnaire developed in Norway.

This study shows how important and effective a research user group can be inworking with researchers in developing quality care indicators for osteoarthritis foruse in a research study and, potentially, routine use in primary care. The questionnaireis intended to benefit patients by enabling the assessment of the quality of primarycare for osteoarthritis from a patient's perspective. The OA QI (UK) has been used toexamine differences in the quality of osteoarthritis care in four European countries.

Abstract:BackgroundPeople with osteoarthritis (OA) desire high quality care, support and informationabout OA. However, the quality of care for people with OA in general practice isnot routinely collected. Quality Indicators (QI) can be used to benefit patients bymeasuring whether minimum standards of quality care (e.g. NICE quality standards) arebeing met from a patient perspective. A Research User Group (RUG) worked withresearchers to co-produce a set of self-report, patient-generated QIs for OA. The QIswere intended for use in the MOSAICS study, which developed and evaluated anew model of supported self-management of OA to implement the NICEguidelines. We report on 1) the co-development of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire(Continued on next page)

2016 Blackburn et al. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction inany medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commonslicense, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

(Continued from previous page)for primary care; and 2) the comparison of the content of the OA QI (UK)questionnaire with a parallel questionnaire developed in Norway for theMusculoskeletal Pain in Ullensaker (MUST) study.

MethodsResearchers were invited to OA RUG meetings. Firstly, RUG members were askedto consider factors important to patients consulting their general practitioner (GP)for OA and then each person rated their five most important. RUG members thendiscussed these in relation to a systematic review of OA QIs in order to form a listof OA QIs from a patient perspective. RUG members suggested wording andresponse options for a draft OA QI (UK) questionnaire to assess the QIs. FinallyRUG members commented on draft and final versions of the questionnaire andhow it compared with a translated Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire.

ResultsRUG members (5 males, 5 females; aged 52–80 years) attended up to four meetings.

RUG members ranked 20 factors considered most important to patients consultingtheir GP for joint pain. Following discussion, a list of eleven patient-reported QIs forOA consultations were formed. RUG members then suggested the wording andresponse options of 16 draft items – four QIs were split into two or more questionnaireitems to avoid multiple dimensions of care quality within a single item. On comparisonof this to the Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire, RUG members commented that bothquestionnaires contained seven similar QIs. The RUG members and researchers agreedto adopt the Norwegian OA-QI wording for four of these items. RUG members alsorecommended adopting an additional seven items from the Norwegian OA-QI withsome minor word changes to improve their suitability for patients in the UK. Oneother item from the draft OA QI (UK) questionnaire was retained and eight itemswere excluded, resulting in a 15-item final version.

ConclusionsThis study describes the development of patient-reported quality indicators for OAprimary care derived by members of a RUG group, working in partnership with theresearch team throughout the study. The OA QI (UK) supports the NICE qualitystandards for OA and they have been successfully used to assess the quality of OAconsultations in primary care in the MOSAICS study. The OA QI (UK) has the potentialfor routine use in primary care to assess the quality of OA care provided to patients.

Ongoing research using both the UK and Norwegian OA-QI questionnaires isassessing the self-reported quality of OA care in different European populations.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Quality indicator, Patient-reported, Patient and publicinvolvement, Primary care, Impact

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of joint pain and years lived with disability

worldwide causing considerable detrimental impact on daily activities and quality of

life OA is one of the main reasons for musculoskeletal consultations with ageneral practitioner by older adults

High quality care is described as clinically effective, personal and safe, which is delivered

to all users of a health service in all aspects of care . However, previous studies have

shown that the quality of care provided to patients with OA in primary care is suboptimal

] and varies according to patient age and OA severity ]. Research has shown thatpatients with OA need more information and education about the condition, diet, exer-

cise, aids, and better support for self-management ]. However, core recommended

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

treatments such as exercise, weight loss and the provision of written information is under-

used for patients with OA [. Furthermore many core treatment are initiated by the pa-

tients themselves rather than doctor initiated [].

Several international guidelines exist which provide recommendations for the man-

agement of OA [International quality standards for OA have also been

developed such as those recently published by the National Institute for Health &

Care Excellence (NICE) [and the European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveil-

lance and Information Network (eumusc.net) Yet there are no robust or rou-

tinely collected measures used currently in general practice to monitor the quality of

care for people with OA although an OA e-template for use during consultations

in primary care has recently been developed and tested

Quality indicators (QI) are ‘specific and measurable elements of practice that can be

used to assess the quality of care' They are used to assess care quality accordingto defined standards of care (e.g. NICE eumusc.net QIs typically assess the

processes of care given to patients by measuring what the provider can offer

patients and examining whether standards of care are being implemented.

A systematic review identified 15 QIs which are broadly applicable with current inter-

national guidance for the assessment of non-pharmacological and pharmacological

management of OA in primary care however the authors recommended an in-

creased use of QIs in primary care from the patient perspective.

The Management of OSteoArthritis In ConsultationS (MOSAICS) study devel-

oped and evaluated a new model of supported self-management of OA to implement

the NICE guidelines for OA in primary care The MOSAICS study aimed to evalu-

ate the new model of supported self-management for OA in primary care, in terms of

the quality of care from both a clinical and a patient perspective (see Additional file

for more information about the MOSAICS study). The findings of the MOSAICS

study are subject to other papers in production. However, at the time of designing

the MOSAICS study, there was a lack of evidence regarding the experiences of pa-

tients with OA in primary care and there were few appropriate quality indicators that

captured the quality of primary care for OA from the patient perspective. Active and

meaningful patient and public involvement (PPI) is increasingly viewed and encour-

aged as integral part of the research process to improve its quality and relevance

–Therefore the collaboration between the researchers and the RUG describedin this article led to development of patient reported QIs for the MOSAICS model of

self-support in primary care.

During the course of the MOSAICS study, the research team became aware of a

questionnaire capturing the patient perspective of the quality of OA primary care being

developed in Norway. The OsteoArthritis Quality Indicator (OA-QI) has since been

validated for use to measure the quality of primary care for OA in a Norwegian popula-

tion The Norwegian OA-QI, comprises 17 questions related to patient education

and information, regular provider assessments, referrals, and pharmacologic treatment.

The tool was developed by team of researchers and OA clinicians, with input from two

patient partners who gave feedback on the content of the finalised questionnaire. The

results of the validation study are reported elsewhere ].

We report on the co-production of a set of self-report, RUG-generated QIs to cap-

ture the quality of primary care management of OA. We also compare the RUG-

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

generated OA QI (UK) questionnaire with a Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire devel-

oped in parallel, leading to a final recommended OA QI (UK) questionnaire.

The manuscript was written using the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Pa-

tients and Public (GRIPP) checklist for reporting Patient and Public Involvement

(PPI) in research This checklist provides a structure for improving the quality of

reporting of the PPI and is designed for studies that have included some form of pa-

tient and public involvement in research. The authors have referred to the checklist

to ensure all the relevant aspects of PPI in this study were reported.

PPI good practice

The PPI described in this article took place at the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care

Centre, Keele University. This institution takes an explicit and systematic approach to

involvement of patients and the public in research Formed in 2006, a Research

User Group (RUG) was established to embed PPI across the whole of the Centre's re-search activities and is supported by a dedicated PPI team and core funding. Cur-

rently, the RUG has over 60 members actively involved on over 60 projects, recruited

on a basis of ‘expertise by experience' of musculoskeletal and other long term condi-tions. Some RUG members have more experience in involvement in research than

other members, though all provide the lay perspective of their health condition. Our

approach to patient involvement draws on previous experience [and recom-mendations for the good practice of PPI so that RUG members can

provide meaningful contributions to the research process (see Additional file for

more information about the RUG).

Our good practice principles include holding meetings in accessible venues at con-

venient times; allocated parking; meeting and greeting on arrival; training and support;

inclusion of regular breaks during meetings; payment for RUG members' time and con-tribution (if wanted); and reimbursement of expenses. Meetings between researchers

and RUG members are made actively ‘jargon-free' and any technical terms are ex-plained in plain English.

The MOSAICS study investigated whether a new way of supporting self-management,

delivered during an OA consultation in primary care, could offer a clinically practical

approach to implementing the core NICE recommendations We describe here the

development of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire by the RUG group for use in the MO-

SAICS study in Stage 1, the comparison of this with a Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire

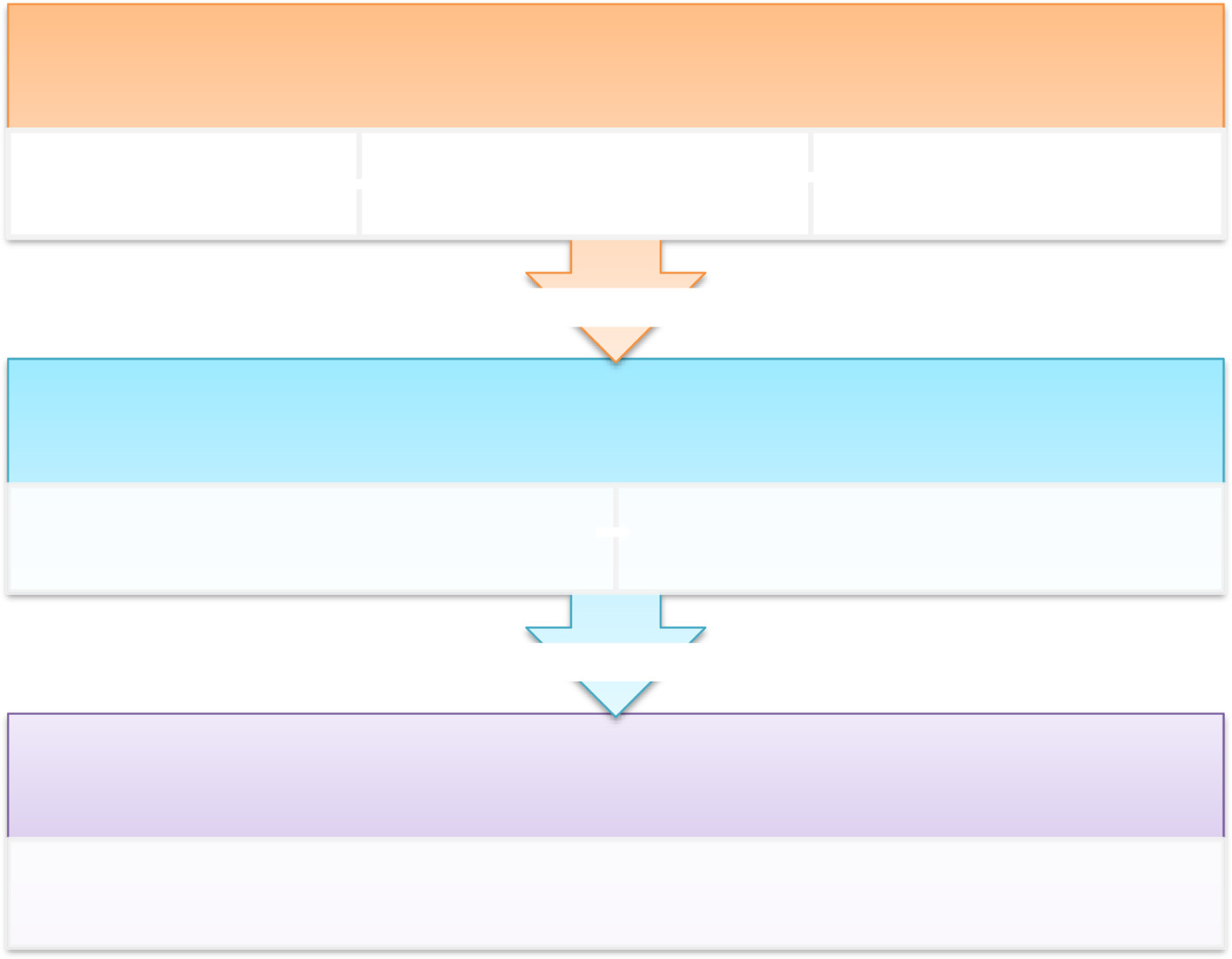

in Stage 2, and review of the finalised OA QI (UK) questionnaire in Stage 3. Figure

provides an overview of the process.

Patient and public involvement in this study

In 2009, RUG members with OA were invited to form an OA PPI group to work in

partnership with researchers throughout the MOSAICS study, including the develop-

ment of patient-reported QIs, set within a wider five year programme of research into

OA Furthermore, two members (AH: a former member of the wider Research

User group and now PPI Support Worker/Coordinator; and RT: Lay member of the

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Fig. 1 Overview of the stages of development of the OA QI

OA Research User Group) have co-authored this article, including writing the plain

English and providing detailed comments on the manuscript prior to the final submission.

During the course of the MOSAICS study, members of the research team met

with RUG members to co-produce the OA QI (UK) questionnaire for use in the

MOSAICS study. The discussion meetings were facilitated by the Centre's PPI Sup-port Worker/Coordinator, the MOSAICS study Chief Investigator and a trial coord-

inator. The PPI Support Worker/Coordinator provided a key role by attend the

meetings with RUG members to provide assistance and support, prior, during and

after meetings. The MOSAICS study Chief Investigator (KD) has collaborated with

the RUG on numerous research studies and is currently the senior academic lead

for PPI in the Centre. All trial coordinators at the Centre have a responsibility for

ensuring PPI in their respective studies and have lots of experience of collaborating

with RUG members.

Discussion notes from the meetings were recorded on flip charts and in meeting mi-

nutes. Following each meeting, a summary of the outcomes and decisions written in

plain English was sent to the RUG members to acknowledge their contribution and ver-

ify that all views had been captured. RUG members were also given the opportunity for

further comment at the start of the next meeting.

It was not intended to formally evaluate the PPI interaction and the RUG members'

experience in the process. However, the impact of the RUG members is described in

this article in the form of the co-produced OA QI (UK) questionnaire for use in the

MOSAICS study.

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Ethical approval for the PPI activities was not sought because the RUG members

were acting as specialist advisers, providing valuable knowledge and expertise based on

their experience of a health condition or public health concern and their involvement did

not raise any ethical concerns []. However, the full MOSAICS research programme was

approved by the North West 1 Research Ethics Committee, Cheshire, UK (REC reference:

Stage 1: development of the OA QI questionnaire

Members of the OA RUG group (n = 10) were invited to a series of four discussion

groups with the research team to develop the patient-reported QIs for patients with

OA treated in primary care. The discussion groups took place over a three year period

from 2009–2012. The objectives of the discussion groups were i) to understand theaims of MOSAICS and roles and expectations of the RUG members, ii) to identify im-

portant and relevant quality indicators for patients with OA when consulting in pri-

mary care, and iii) to develop wording and response options for a self-report OA QI

(UK) questionnaire to assess the identified quality indicators (Fig.

i) Understanding the aims of MOSAICS and roles and expectations of the RUG

In the first meeting, a plain English summary of the MOSAICS study was

introduced to set the context for the meetings and outline roles of the RUG

ii) Identifying important and relevant quality indicators of OA in primary care

consultations from a patient's perspectiveDuring facilitated discussions, RUG members identified factors they considered to

be important to patients with OA consulting their general practitioner (GP) to

help identify potential QIs for OA consultations. Each RUG member then ranked

(1 to 5) the top five factors they considered the most important. Any factors not

selected as ‘most important' by at least one RUG member were excluded fromfurther discussions.

The research team then presented RUG members with five QIs identified from

a previous systematic review [] (Fig. ). These QIs were selected on the basis

of their relevance for the MOSAICS model OA consultation of supported

self-management and were used to stimulate discussion within the RUG group.

The QIs included whether during GP consultations, patients have been offered

education and advice about their disease, exercise and weight loss, and offered

pain relief in the form of paracetamol and topical (skin applied) non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS). RUG members were asked to 1) consider

each QI alongside the initial list of important factors when consulting their GP

for OA and add other factors as necessary, and 2) suggest potential QIs and

questions which could capture the quality of care from a patient perspective.

iii) Developing the wording and response options for a self-report OA QI (UK)

Based on the list of important factors suggested by RUG members, an initial

set of patient-reported OA QIs were generated. From this list, wording for

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Fig. 2 Five quality indicators identified from a systematic review used to stimulate discussion with theRUG members

questionnaire items to assess the QIs were drafted for an OA QI (UK) question-

naire. Over a further two meetings, RUG members and the research team

worked together to refine and finalise the questions so they were suitable for

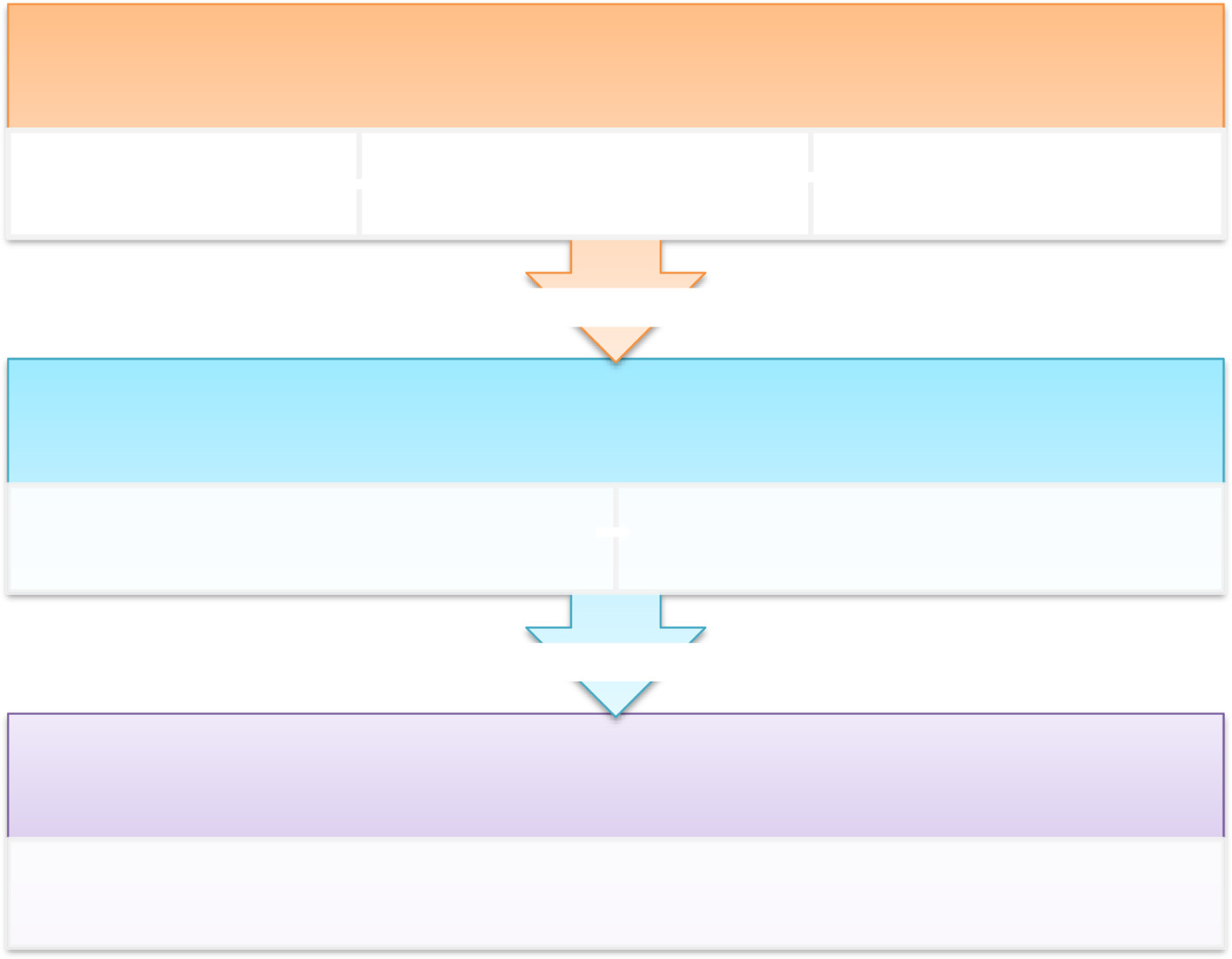

use in a research trial. (See Fig. for an outline of the process). Feedback and

suggestions on the wording of the items and the scoring method (response

Fig. 3 Overview of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire item development

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

options) were given on documents mailed to the RUG members between

Stage 2: comparison of the OA QI (UK) with the Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire

The RUG group and MOSAICS study team had not planned to test the measurement

(or psychometric) properties of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire. As mentioned earlier in

this article, a similar OA QI questionnaire was being developed for use in primary care

in Norway (the Norwegian OA-QI)

In order to establish the measurement properties of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire,

the Norwegian developers (NO, KH) produced an English translation of a draft ver-

sion of the Norwegian OA-QI for item content and scoring comparison. RUG mem-

bers reviewed this and compared its content with the OA QI (UK) questionnaire

during the third meeting. Based on this comparison, RUG members suggested how

the OA QI (UK) questionnaire could be refined and modified to include items in the

validated Norwegian OA-QI. Where QIs in each questionnaire were similar, RUG

members considered the appropriateness of the wording used in the Norwegian OA-

QI for potential use.

Stage 3: review of the finalised OA QI (UK) questionnaire

During the last meeting, the RUG reviewed, commented and suggested refinements to

the OA QI (UK) questionnaire for primary care. RUG members were also asked to as-

sess the face validity of the questionnaire by commenting further on its appearance and

layout, ease of completion, and to identify anything ambiguous or difficult to under-

stand. The research team also compared the content of the OA QI (UK) questionnaire

with the other questionnaires and data collected in the MOSAICS to check for un-

Patient and public involvement

All of the RUG members (males 5, females 5) had OA and were aged 52–80 years. Fourmeetings were held during the three year period. All meetings were attended by be-

tween three and ten members.

Stage 1: development of the OA quality indicators

Identifying important and relevant quality indicators of OA in primary care consultations

from a patient's perspectiveRUG members initially discussed and identified 30 factors considered important and

relevant to patients consulting their GP for OA. From this list, RUG members chose 20

factors as ‘most important' (Table which were grouped into the following domains:information about OA; information about treatment for OA; information about self-

management for OA; advice about using medications to relieve joint pain; information

about exercise and activities; referrals to activity or exercise programmes, and the qual-

ity of the consultation with the GP. These domains formed an initial list of seven

patient-reported QIs for OA consultations. Following the review of the five quality indi-

cators identified from a systematic review an additional four QIs appropriate from

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Table 1 Selection of factors considered most important to patients with OA consulting their GP

Factors ranked most important Frequency Draft Patient reported QIs for

to patients with OA consulting

OA (‘In the last 3 months….')

their GP (top 5 on a 1-5 scale)

draft OA QI(UK)questionnaire

Want to know about risks

You have received

or side effects from

information regarding

treatment for joint problemfrom your surgery

Want to know about pain

management [medications]

Want to know about the

expectations of any possiblehelp, i.e. whether you needan X-ray/pain clinic/operation/investigations/scan/referto a consultant

Want to know about surgery

and also what to do when theconsultant/surgeon saysbecause of the cause there isnothing they can do

Want to get pain down to a

level you can cope with

What you want is an

You have received

exchange between the GP

information about your joint

problem from your surgery

How OA will affect quality

When you get more pain, you

Pain has gone – will it stay

Consultations are a

combination of medical andpatient expectations

Age means that OA is seen

Want to know if it's a serious

Want to know about

You have received advice and 3

techniques to [self] manage

support on how you might

help yourself to manage or

deal with your joint problem

How to best use anti-

You have been offered advice 4

inflammatory medications

about medications (to relieve

relieve joint pain

Want to know about should

You have been offered

we be doing more or less

information or advice on

exercise or activity to helpwith your joint problem

Did certain things to help

You have been offered a

with quality of life (e.g. went

referral to an exercise or

to gym, go swimming)

activity programme for your

The quality of consultation is

You are satisfied with the

important so that you know

overall quality of the

you shouldn't just soldier on

consultation with his/her GP

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Table 1 Selection of factors considered most important to patients with OA consulting their GP(Continued)

Consultation to take a holistic

approach/to ask patient aboutfeelings and thoughts aboutthe problem*

Previous consultation was a

waste of time and I haven'tbeen back

Don't want to waste the GP's

Additional QIs following the discussion of the five treatment scenarios

Follow up review -

You have been given a

follow-up review of your jointproblem

You have been offered a

referral for physiotherapy foryour joint problem

You have received advice

about body weight and jointpain

You have received a referral

for weight loss services

aQuestionnaire items not created for this QI as it was adequately captured elsewhere in the larger MOSAICS surveybQuestionnaire items not created for these two QIs as they were initially captured elsewhere in the larger MOSAICS study

a patient perspective (‘patient has received a follow-up review of his/her joint problem';‘patient has received a referral for physiotherapy'; ‘patient has received advice aboutbody weight and joint pain', ‘patient has received a referral for weight loss services') wereadded. Therefore, 11 unique QIs were identified (Table

Developing the wording and response options for a self-report OA QI (UK) questionnaire

Using the list of eleven self-reported QIs for OA consultations, RUG members suggested

questionnaire wording and response options to assess each QI. RUG members stated that

the 3-month recall period, as determined by the MOSAICS trial design, was an appropri-

ate period to have had at least one consultation with their GP for a joint problem. They

also suggested that the response options should be a simple 3-level response format for all

questions for the draft questionnaire: "Yes", "No", and "Don't know".

The RUG members' suggestions were drafted into a questionnaire. Views of the over-

all quality of the consultation were captured in other parts of the MOSAICS study, so

this item was not included in the questionnaire. To avoid multiple dimensions of care

within a single question, one QI (advice about using medications to relieve joint pain)

was split into four questions, two QIs (information about self-management for OA; ad-

vice about exercise or activities) into three items, and one other QI (follow up review)

was split into two questions, respectively.

The resultant draft OA QI (UK) questionnaire comprised 16 items. In the second

group meeting, RUG members reviewed the draft questionnaire and worked with the

research team to refine its content. RUG members provided further comments on the

ease of understanding and relevance of the questions. They suggested wording for the

questionnaire instructions and changes to improve the clarity, specificity and order of

the questions. RUG members suggested changing the wording for the ‘don't know'

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

response option where relevant if the respondent could not remember, if they had not

received an aspect of care, or if the question was not applicable.

Stage 2: comparison of the OA QI (UK) with the Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire

After reviewing both questionnaires, RUG members suggested that the draft OA QI

(UK) questionnaire and the draft Norwegian OA-QI were similar. Seven items in the

draft OA QI (UK) questionnaire capturing six quality indicators: (information about

OA, information about treatment for OA, information about self-managing OA, advice

about exercise or activities for OA, referral to exercise or activity programmes for OA,

advice about the use of medications to relieve joint pain) used comparable wording to

those included in the draft Norwegian OA-QI (Table Of these, RUG members and

the research team agreed to retain the wording used in the draft OA QI (UK) question-

naire for three items and adopt all or some of wording in the draft Norwegian OA-QI

for the other four items for the final questionnaire. Both questionnaires used similar

three-level response options.

RUG members recommended that a further seven items (capturing six QIs) included

in the Norwegian OA-QI were relevant and should be added to the UK questionnaire.

They suggested minor changes to wording to make them more appropriate for the UK

(Table Three other items from the Norwegian OA-QI questionnaire (advice about

changing lifestyle; assessment of daily activities; assessment of pain) were captured else-

where in the MOSAICS study and therefore not required for the OA QI (UK) question-

naire. Nine items from the draft OA QI (UK) that were not present in the Norwegian

OA-QI were retained at this stage. Therefore, at the end of Stage 2, the draft version of

the OA QI (UK) questionnaire contained 23 items (Fig.

Stage 3: review of the finalised OA QI (UK) questionnaire

The iterative process of redrafting and reviewing the questionnaire continued into the

fourth meeting until the RUG members and researchers agreed on the final draft ver-

sion. Along with subtle changes to item wording suggested by RUG members, the re-

search team and RUG members agreed to retain one item from the draft OA QI (UK)

(on support for self-managing OA). Eight items from the draft OA QI (UK) (support

from ‘surgery' or other health care professionals to help you manage your joint problem;follow up review received (2 items); current participation in exercise; exercise programme

suggested; referral for physiotherapy; advice about taking paracetamol received; advice

about taking capsaicin cream received) were either covered elsewhere in the MOSAICS

study too generic or were too similar to other items (Table ). Therefore, these

eight items were not included in the final 15-item OA QI (UK) questionnaire (see

Additional file RUG members and researchers agreed that the length of the final

version of the questionnaire was appropriate to capture important quality indicators

of OA in primary care consultations from a patient's perspective without overburden-ing those who complete it.

This study describes the development of patient-reported quality indicators question-

naire for the primary care of osteoarthritis, which were derived by members of a

Table 2 Comparison of the draft OA QI (UK) and Norwegian OA-QI questionnaires

Quality Indicator

Draft Norwegian OA-QI

Published Norwegian OA-QI

RUG and research team's

RUG and research team's

(first English translation)

(tested for validity and reliability)a

recommendations for final

OA QI (UK) (✓ = retain or

(Changes to wording

add; X = not required)

for final OA QI (UK))

Patient has received

Have you been given any

Have you been informed about

Have you been given information

Retain (with draft OA

information about OA

information about your joint

how the disease naturally evolves?

about how the disease usually

QI (UK) wording and

problem(s) from your surgery?

develops over time?

‘written or verbal'

information included)

Patient has received

Have you been given any information

Have you been informed about treatment?

Have you been given information

Retain (Adopt draft

information about

regarding treatment for your joint

about different treatment

problem(s) from your surgery?

Patient has received

Have you been given any advice

Have you been informed about

Have you been given information

Retain (with draft OA

information about

on how you might help yourself

about how you can live with

to manage or deal with your

joint problem(s)?

Patient has received

Have you been given any support

Retain (with draft OA

information about

on how you might help yourself

to manage or deal with your

joint problem(s)?

Patient has received

Have you been given any support

information about

from your ‘surgery' or other health

care professionals e.g. physiotherapists

or occupational therapists tohelp you manage your jointproblem(s)?

Patient has received

Have you been given a follow

a follow up review

up review of your joint problem(s)at least once?

Patient has received

Have you been given a follow up

a follow up review

review of your joint problem(s) ever?

Patient has received

Have you been offered advice

Have you been given information

advice about changing

about lifestyle change?

about how you can change

Table 2 Comparison of the draft OA QI (UK) and Norwegian OA-QI questionnaires (Continued)

Patient has received

Do you participate in any exercise?

advice about exerciseor activities for OA(current participationin exercise)

Patient has received

Have you been offered information

Have you been informed about

Have you been given

Retain (with draft OA QI

advice about exercise

or advice on exercise or physical

the impact of muscle strengthening

information about the importance

(UK) wording but ‘muscle

or activities for OA

activity to help you with your joint

or aerobic exercise programs?

of physical activity and exercise?

strengthening' included)

Patient has received

Have you been offered a referral

Have you been referred to services

Have you been referred to someone

Adopt draft Norwegian

a referral to exercise

for exercise or activity programme

for a directed or supervised

who can advise you about physical

or activity programmes

for your joint problem(s) (e.g. tai chi,

strengthening or aerobic exercise

activity and exercise

swimming, keep fit)?

(e.g. a physiotherapist)?

Patient has received

Has an exercise or activity

referral about exercise

programme been suggested to

or activities for OA

help you manage with your

(exercise programme

joint problem(s)?

Patient has received

Have you been advised to lose

If you are overweight, have

Adopt draft Norwegian

advice about body

weight, if you are overweight

you been advised to lose weight?

weight and joint pain

(‘if you are overweight'removed)

Patient has received

Have you been referred to

If you are overweight, have you

Adopt draft Norwegian

a referral for weight

services for losing weight,

been referred to someone who

OA-QI wording (‘if you

if you are overweight and obese?

can help you to lose weight?

are overweight' removedand examples of weightloss services added)

Patient has received

If you have had problems related

If you have had problems related to

a referral for an

to activities of daily living, have

daily activities, have these problems

these problems been assessed

been assessed by health personnel

activities of daily

in the last year?

in the last year?

Table 2 Comparison of the draft OA QI (UK) and Norwegian OA-QI questionnaires (Continued)

Patient has received

Have you been offered a referral

for physiotherapy for your

joint problem(s)?

Patient has received

If you have problems related to

If you have problems related to

Adopt draft Norwegian

a referral for an

other activities of daily living,

other daily activities, has your need

OA-QI wording (‘assistive

assessment for aids

has your need for assistive devices

different appliances and aids been

devices' changed to

(e.g. splints, assistive technology

assessed (e.g. splints, assistive

‘appliances and

for cooking or personal hygiene)

technology for cooking or personal

aids to daily living')

hygiene, a special chair)?

Patient has received

If you have problems related to

If you have problems with walking,

Adopt draft Norwegian

a referral for an

walking, has your need for

has your need for a walking aid

ambulatory assistive devices

been assessed (e.g. stick, crutch,

(‘ambulatory assistive

(e.g. stick, crutch, or walker)

devices' changed to ‘a

Patient has received

If you have pain, has your

If you have pain, has it been

pain been assessed in the last year?

assessed in the past year?

Patient has received

Have you been offered advice by

If you have pain, was paracetamol

If you have pain, was

Adopt draft Norwegian

advice about the use

your surgery about taking

the recommended pharmacological

acetaminophen the first medicine

of medications to

paracetamol before taking other

therapy for your osteoarthritic pain?

that was recommend for your

relieve joint pain

osteoarthritic pain?

Patient has received

Have you been offered advice by

advice about the use

your surgery about taking the

of medications to

following medication: paracetamol?

relieve joint pain

Patient has received

If you have prolonged severe pain,

If you have prolonged severe pain,

Adopt draft Norwegian

advice about the use

for which paracetamol does not

which is not relieved sufficiently

of medications to

provide pain relief, have you been

by paracetamol, have you been

(‘analgesic' changed to

relieve joint pain

offered stronger analgesic drugs

offered stronger pain killers

(e.g., coproxamol, co-dydramol,

for stronger analgesia)

Table 2 Comparison of the draft OA QI (UK) and Norwegian OA-QI questionnaires (Continued)

Patient has received

Have you been offered advice by

If you use anti-inflammatory drugs

If you are taking antiinflammatory

Adopt draft Norwegian

your surgery about taking the

(e.g. …), have you received information

drugs, have you been given

use of medications

following medication: topical

about the effects and potential side

information about the effects

to relieve joint pain

anti-inflammatory creams or gels

effects associated with this drug?

and possible side effects of this

(e.g. Votarol gel, diclofenac,

medicine (e.g., ibuprofen, Nurofen,

drug information)

ibuprofen cream)?

Brufen, diclofenac, Voltarol,

naproxen, Naprosyn, Celebrex)?

Patient has received

Have you been offered advice

advice about the use

by your surgery about taking

of medications to

the following medication:

relieve joint pain

(capsaicin cream)

Patient has received

If you have experienced an

If you have experienced an acute

Adopt draft Norwegian

advice about the use

acute deterioration in symptoms,

deterioration of your symptoms,

of medications to

has a corticosteroid injection been

has a corticosteroid injection

relieve joint pain

(Consideration forcorticosteroid injection)

If you experience severe symptomatic

If you are severely troubled

Adopt draft Norwegian

considered for referral

osteoarthritis, and pharmacological

by your osteoarthritis, and

therapy and exercises have no

exercise and medicine

response, have you been referred

do not help, have you been

for evaluation of surgery (e.g.,

referred and assessed for an

total joint replacement)?

operation (e.g., joint replacement)?

aFinal wording of Norwegian OA-QI was published after the OA RUG group reviewed and compared the draft OA QI (UK) with the draft Norwegian OA-QI

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Research User Group, working in partnership with researchers. The OA QI (UK) has

been successfully used in a large randomized control trial of a new model of sup-

ported self-management of OA (the MOSAICS study) and a study to audit the

quality of OA primary care practice in the United Kingdom, Norway, Denmark and

Portugal. While the full results of these studies are subject to other papers in produc-

tion, the focus of this article is on the role and impact of PPI to develop the OA QI

The active, meaningful and on-going involvement of patients as partners in the research

process is a strength of this study. The perspectives of patients may differ from the per-

spectives of healthcare professionals or information recorded by professionals in medical

records Therefore, the unique perspectives of patients with OA based on their

experience of the condition and past consultations in primary care has enhanced the de-

velopment of patient-centred quality indicators for use in OA primary care. We acknowl-

edged that the PPI input in this study incorporated the perspectives of a small group of

patients, as small as three people for one meeting. Also, the RUG membership was not

greatly diverse, in terms of age, ethnicity, and physical abilities. While obtaining a range of

perspectives is the objective of PPI in research and not necessarily ‘representativeness', it ispossible however that the OA QI (UK) does not cover the full range of quality indicators

relevant to the population of patients with OA. Nevertheless, the sequential and iterative

development of the OA QI (UK) allowed the researchers and RUG members to review

and critique earlier suggestions made by the RUG.

The RUG group identified important factors related to the quality of OA care pro-

vided by a primary care healthcare professional and suggested item wording for a ques-

tionnaire. By comparing the OA QI (UK) questionnaire with a similar one developed in

Norway, the RUG members helped redraft and refine the final questionnaire. The RUG

collaborated with the research team throughout the development of the OA QI (UK)

but were also involved on other aspects of the MOSAICS study such as developing a self-

management guidebook for patients with OA and participant information sheets , .

Regular meetings were set up for these. Though there were extended gaps between meet-

ings regarding the OA QI (UK) development, the timings of the meetings were governed

by the MOSAICS study timeline. However, RUG members were provided with feedback

of the meeting and given the opportunity to comment. This process built upon existing

working relationships and trust between the RUG and researchers.

The research team embraced the contribution of the RUG members and imple-

mented many of their suggestions. The concepts included in the finalised OA QI (UK)

were generated by the RUG members. Working in collaboration the RUG members

and the research team shaped the items in survey questions suitable for use in a re-

search trial. The Chief Investigator did not make decisions on the final content of the

questionnaire without the fully informed RUG and explained if information was already

captured elsewhere in the MOSAICS study. For example, RUG members did identify

eight other important and relevant QIs not included in the final version of the OA QI

(UK). So, to avoid repetition and participant burden in the MOSAICS study, these eight

items were not included in the final 15-item OA QI (UK) questionnaire. These deci-

sions were fully explained to the RUG members. Therefore, the RUG members' contri-

bution ensured that the resulting OA QI (UK) incorporated issues relevant to patients

with OA, written in a language that patients found easy to understand.

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

The OA QI (UK) was developed to assess the uptake of treatment recommended by

NICE and complements the new NICE Quality Standards of Care for OA

Using evidence from a systematic review the OA QI (UK) is a 15-item question-

naire that covers treatments offered by healthcare professionals in primary care. The

OA QI (UK) supports the recently published NICE Quality Standards of Care for OA

and the European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveillance and Information Net-

work (eumusc.net) recommendations for the OA Standards of Care across European

member states For example, it captures five of the eight NICE quality statements

either fully or partially from a patient's viewpoint. The OA QI (UK) and the NorwegianOA-QI also sit alongside established outcome measures of OA management and provide

process measures of the quality of OA care. The eumusc.net has developed OA

health care quality indicators (HCQI-OA) and an accompanying audit tool for clini-

cians and health care providers The OA QI (UK) and HCQI-OA both include

six similar quality indicators. This questionnaire, if used in routine practice, will

have the patients' perspectives embedded in an evaluation of care quality. Thoughdeveloped for use across primary care settings, the OA QI (UK) may be further re-

fined to meet the specific needs and priorities of local health care settings, if

Establishing the measurement properties of a questionnaire is an important step in

its development. The use of scientifically sound and decision-relevant measures al-

lows the collection of evidence on the benefits of intervention (or care practices) from

a patients' perspective [The OA QI (UK) and the Norwegian OA-QI were devel-oped in parallel. Given the similarity between the construct and wording of the two

questionnaires and the direct additions of items from the Norwegian OA-QI, the UK

version ‘adopted' the measurement properties of the validated Norwegian version.

The comparison of the questionnaires used a translated, draft version of the Norwe-

gian OA-QI. However, the Norwegian OA-QI was further refined with some changes

to the item wording before validity and reliability testing. Though they are very simi-

lar in content and wording, the finalised, validated Norwegian OA-QI was published

after the OA QI (UK) was produced and implemented in the MOSAICS study. The

measurement properties of the OA QI (UK) was not tested because the 14 (out of the

15 items) were identical or contained subtle changes in wording to items in the vali-

dated Norwegian questionnaire. Therefore, conducting a full validation study on the

OA QI (UK) questionnaire was not justified at this stage. However, the assumption

that the measurement properties of the two questionnaires are similar may need fur-

ther exploration.

The overall positive feedback from RUG members on the Norwegian OA-QI en-

abled adaptations to the OA QI (UK) to be made with confidence. The development

of the both questionnaires was coincidental. Although there was differences in how

they were developed (one mainly patient-led and the other mainly researcher/clinician

derived), this study has demonstrated that patients and researchers have similar ex-

pectations about what constitutes good quality care in OA in different European

countries. It also highlights the value of the active, meaningful and useful contribu-

tion of patients in the research process. Furthermore, the consistency of quality indi-

cators for OA consultations in two European countries has now provided a unique

opportunity to compare QIs across European countries [This may lead to the

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

development of a single, combined questionnaire for use in routine clinical practice

to assess the quality of OA care provided to patients.

This study has demonstrated that active involvement of patients in research, working

in partnership with researchers, identified important and relevant OA quality indica-

tors, and developed a self-reported questionnaire to measure them. The OA QI (UK)

questionnaire aligns with current national and international standards and process

measures of OA care (e.g. NICE, eumusc.net) and is consistent with quality indicators

validated for Norwegian OA consultations. The development of two OA quality indica-

tor questionnaires was coincidental but has led to further research to compare patient-

reported OA QIs across European countries. Following this work, a single refined OA

QI questionnaire for use in routine clinical practice is planned.

Overview of the Managing Osteoarthritis in Consultations (MOSAICS) study. (DOCX 12 kb)

Overview of Patient and Public Involvement in the Institute of Primary Care and Health,Keele University. (DOCX 12 kb)

The Osteoarthritis Quality Indicators (UK) Questionnaire. (DOCX 56 kb)

Abbreviationseumusc.net: European musculoskeletal conditions surveillance and information network; GP: general practitioner;GRIPP: guidance for reporting involvement of patients and public; HCQI-OA: health care quality indicators forosteoarthritis; MOSAICS: Management of OSteoArthritis In ConsultationS; NICE: National Institute for Health and CareExcellence; OA: osteoarthritis; PPI: patient and public involvement; QI(s): quality indicator(s); RUG: research user group;UK: United Kingdom.

Competing interestsK.D. has been an invited speaker to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) conference and a member ofthe NICE OA guideline development group. Keele University has received payments and reimbursements of travel andother expenses related to these activities. K.D. has no financial relationships with any organizations that may have aninterest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years. J.J.E. provides general medical services and benefits financiallyfrom the Quality & Outcomes Framework of the General Medical Services contract; he has also been an invitedspeaker to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) conference. All other authors have declared no conflictsof interest.

Authors' contributionSB and KD wrote the first draft of the paper; AH and RT (Lay members of the OA Research User Group) wrote theplain English summary. AH, RT, JB, NØ, KB, JE, KJ, CJ gave detailed comments for the final submission. All authors readand approved the final manuscript.

AcknowledgementsThis work presented in this paper was paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institutefor Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant (RP-PG-0407-10386). The views expressed in this paper are those ofthe author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We are grateful to thePrimary Care Research Consortium Board and by Arthritis Research UK for their support of the RUG. The authorswould especially like to thank the OA Research User Group (Jo Bird, Brian Dudley, Teresa George, John Murphy,Chris Pope, Jeannette Shipley, Alan Sutton, Robert Taylor, Christine Walker, Anne Worral) for all their support andassistance with this study. We are also thankful to Carol Rhodes and June Handy for their time and effortsupporting and working with the RUG. Time for CJ and KD was part funded by the National Institute for HealthResearch (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Research and Care West Midlands. KD is part-funded byKnowledge Mobilisation Fellowships from the NIHR (KMRF-2014-03-002).

Author details1Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University,Keele, UK. 2Lay Member of the Osteoarthritis Research User Group, Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, ResearchInstitute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University, Keele, UK. 3Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

Received: 8 August 2015 Accepted: 9 February 2016

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223.

Arthritis Research UK. Osteoarthritis in general practice: Data and perspectives. Accessed 22 December 2014.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CG177 osteoarthritis: Care and management in adults.

Accessed 23 December 2014.

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendationsfor the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1125–35.

Cook C, Pietrobon R, Hegedus E. Osteoarthritis and the impact on quality of life health indicators. Rheumatol Int.

2007;27:315–21.

Darzi A. High Quality Care for all: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London: The Stationery Office; 2008.

Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C. P. Croft in collaboration with the Primary Care Rheumatology Society. Primary caretreatment of knee pain—a survey in older adults. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1694–700.

Edwards JJ, Khanna M, Jordan KP, Jordan JL, Bedson J, Dziedzic KS. Quality indicators for the primary care ofosteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:490–8.

Ganz DA, Chang JT, Roth CP, Guan M, Kamberg CJ, Niu F, et al. Quality of osteoarthritis care for community-dwelling older adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:241–7.

Steel N, Maisey S, Clark A, Fleetcroft R, Howe A. Quality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments:an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:449–54.

Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S, Shekelle P, Breeze E, Marmot M, et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with32 quality indicators: national population survey of adults aged 50 or more in England. BMJ. 2008;337:a957.

Broadbent J, Maisey S, Holland R, Steel N. Recorded quality of primary care for osteoarthritis: an observationalstudy. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:839–43.

Mann C, Gooberman-Hill R. Health care provision for osteoarthritis: concordance between what patients wouldlike and what health professionals think they should have. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:963–72.

Jinks C, Ong BN, Richardson J. A mixed methods study to investigate needs assessment for knee pain anddisability: population and individual perspectives. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:1–9.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of thehand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465–74.

Zhang W, Moskowitz R, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman R, Arden N, et al. OARSI recommendations for themanagement of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:137–62.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality standard for osteoarthritis (QS87). Accessed June, 22 2015.

eumusc.net. Standards of care for people with osteoarthritis . Accessed 03/09 2015.

Goodwin N, Curry N, Naylor C, Ross S, Duldig W. Managing people with long-term conditions. London: The Kings Fund; 2010.

Edwards JJ, Jordan KP, Peat G, Bedson J, Croft PR, Hay EM, et al. Quality of care for OA: the effect of a point-of-care consultation recording template. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:844–53.

Keele University. The osteoarthritis (OA) e-template. Accessed 23 July 2015.

Marshall M, Campbell S, Hacker J, Roland M. Quality Indicators for General Practice. A Practical Guide for HealthProfessionals and Managers. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd; 2002.

Raleigh V, Foot C. Getting the measure of quality: Opportunities and challenges. London: The King's Fund; 2010.

Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, Ong B, Main CJ, Jordan KP, et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritisguidelines: a mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primarycare - the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:95.

INVOLVE. Briefing note three: Why involve members of the public in research? Accessed 23 December 2014.

National Institute for Health Research. Public involvement in your research. Accessed 23 December 2014.

National Institutes of Health. Get Involved at NIH. Accessed 23 December 2014.

INVOLVE. Briefing note eight: Ways that people can be involved in the research cycle. Accessed 3 October 2015.

Østerås N, Garratt A, Grotle M, Natvig B, Kjeken I, Kvien TK, et al. Patient-reported quality of care forosteoarthritis: development and testing of the OsteoArthritis quality indicator questionnaire. Arthritis CareRes. 2013;65:1043–51.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C. The GRIPP checklist:strengthening the quality of patient and publicinvovlement in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:391–9.

Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, Beech R, Dziedzic K, Hughes R, et al. Sustaining patient and public involvement inresearch: a case study of a research centre. J Care Serv Manage. 2013;7:146–54.

Jinks C, Ong BN, O'Neill TJ. The Keele community knee pain forum: action research to engage with stakeholdersabout the prevention of knee pain and disability. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:85.

Grime J, Dudley B. Developing written information on osteoarthritis for patients: facilitating user involvement byexposure to qualitative research. Health Expect. 2014;17:164–73.

Strauss VY, Carter P, Ong BN, Bedson J, Jordan KPJ, Jinks C. Public priorities for joint pain research: results from ageneral population survey. Rheumatology. 2012;51:2075–82.

Blackburn et al. Research Involvement and Engagement (2016) 2:5

Carter P, Beech R, Coxon D, Thomas MJ, Jinks C. Mobilising the experiential knowledge of clinicians, patients andcarers for applied health-care research. Contemp Soc Sci. 2013;8:307–20.

Williamson T, Kenney L, Barker AT, Cooper G, Good T, Healey J, et al. Enhancing public involvement in assistivetechnology design research. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014;10:258–65.

Gooberman-Hill R, Horwood J, Calnan M. Citizens' juries in planning research priorities: process, engagement andoutcome. Health Expect. 2008;11:272–81.

NIHR. School for Primary Care Research. Patient and Public Involvement: Case Studies in Primary Care Research.

Oxford: NIHR School for Primary Care Research; 2014.

National Research Ethics Committee, INVOLVE. Patient and public involvement in research and research ethicscommittee review. Accessed 23 December 2014.

Hewlett SA. Patients and clinicians have different perspectives on outcomes in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:877–9.

Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients' needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards acomprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:32.

Higginbottom A, Jinks C, Bird J, Rhodes C, Blackburn S, Dziedzic K. From Design to Implementation – Patient andPublic Involvement in an Nihr Research Programme in Osteoarthritis in Primary Care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:69.

eumusc.net. Musculoskeletal conditions health care quality indicators (WP6). Accessed 23 December 2014.

eumusc.net. Audit tool OA. Accessed 23December 2014.

Porcheret M, Grime J, Main C, Dziedzic K. Developing a model osteoarthritis consultation: a Delphi consensusexercise. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:25.

Østerås N, Jordan K, Clausen B, Cordeiro C, Dziedzic K, Edwards J, et al. Self-reported quality care for kneeosteoarthritis; comparisons across Denmark, Norway, Portugal and United Kingdom. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000136.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and we will help you at every step:

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal

• We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services

• Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript atwww.biomedcentral.com/submit

Outline placeholder

Source: https://researchinvolvement.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s40900-016-0019-x?site=researchinvolvement.biomedcentral.com

Estudios Constitucionales, Año 8, Nº 2, 2010, pp. 633 - 674. Centro de Estudios Constitucionales de Chile Universidad de Talca "Informe en derecho presentado ante el Tribunal Constitucional en el proceso de inconstitucionalidad del artículo 38 ter de la Ley N° 18.933" Pablo Contreras V., Gonzalo García P., Tomás Jordán D., Álvaro Villanueva R. INFoRME EN DERECHo PRESENTADo

PRESS RELEASE Lyxumia® (lixisenatide)* in Combination with Basal Insulin plus Oral Anti-Diabetics Significantly Improved Glycemic Control – Data show investigational GLP-1 receptor agonist delayed gastric emptying and significantly reduced post-prandial glucose – – Results from the GetGoal Duo 1 and GetGoal-L Phase III studies also presented at