Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Dentalexpress.ma

clinical overview

unique technology for unique results

BioHorizons is dedicated to developing evidence-based and scientifically proven products. From the launch of the External implant system (Maestro) in 1997, to the Laser-Lok 3.0 implant in 2010, dental professionals as well as patients have confidence in our comprehensive portfolio of dental implants and biologics products.

Our commitment to science, innovation and service has aided us in becoming one of the fastest growing companies in the dental industry. BioHorizons has helped restore smiles in 85 markets throughout Asia, North America, South America, Africa, Australia and Europe.

BioHorizons uses science and

innovation to create unique products

with proven surgical and esthetic results.

Our advanced implant technologies, biologic products and computer guided surgery software have made BioHorizons a leading dental implant company.

BioHorizons understands the

importance of providing excellent service. Our global network of

professional representatives and our highly trained customer care support team are well-equipped to meet the needs of patients and clinicians.

The following review presents some of the studies and presentations related to Laser-Lok microchannels.

Laser-Lok abutment study (canine)

Laser-Lok ball abutment case report (human)

Laser-Lok abutment case series (human)

Laser-Lok abutment delayed restoration (human)

Three year prospective, controlled

One year multi-unit versus NobelReplace™ Select

Ten year case study

Four year case study

Three year private practice study

Evidence of connective tissue attachment

Effect of crestal and subcrestal placement

Laser-Lok implants immediately loaded

Immediately loaded sinus augmentation

Immediate placement in the esthetic zone

Development Research

Laser-Lok influence on immediate placement

Predicts minimization of crestal bone stress

Comparison to other implant designs

Epithelium and connective tissue attachment

Improved stabilization and osseointegration

Laser-Lok induces contact guidance

Faster osseointegration and higher bone ingrowth

Bone cell contact guidance

Functionally stable soft tissue interface

Optimized surface dimensions

Directed tissue response

Directed tissue response

Cell orientation & organization

Inhibit cell ingrowth

Suppress fibrous encapsulation

Laser-Lok Technology

Laser-Lok overview

Laser-Lok microchannels is a proprietary dental

implant surface treatment developed from over 20

years of research initiated to create the optimal implant

surface. Through this research, the unique Laser-Lok

surface has been shown to elicit a biologic response

that includes the inhibition of epithelial downgrowth

and the attachment of connective tissue (unlike

Sharpey fibers).2,3 This physical attachment produces

a biologic seal around the implant that protects

and maintains crestal bone health. The Laser-Lok

phenomenon has been shown in post-market studies

to be more effective than other implant designs in

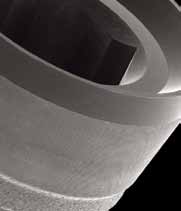

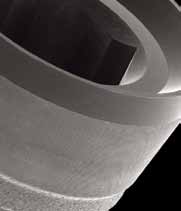

SEM image at 30X showing the Laser-Lok zone

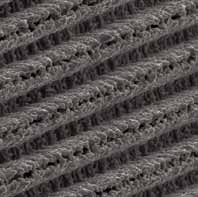

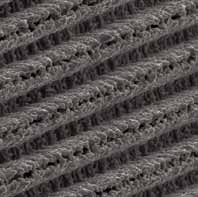

The uniformity of the Laser-Lok microstructure

reducing bone loss.4,5,6,7

on a BioHorizons implant.

and nanostructure is evident using extreme magnification.

Unique surface characteristics

Laser-Lok microchannels is a series of cell-sized circumferential channels that are precisely created using laser ablation technology.

This technology produces extremely consistent microchannels that are optimally sized to attach and organize both osteoblasts and

fibroblasts.8,9 The Laser-Lok microstructure also includes a repeating nanostructure that maximizes surface area and enables cell

pseudopodia and collagen microfibrils to interdigitate with the Laser-Lok surface.

Human histology shows the apical extent of the

Polarized lights show the connective tissue is

Colorized SEM of a dental implant harvested at

junctional epithelium below which there is a

6 months post-op shows the connective tissue is

supracrestal connective tissue attachment to the

physically attached and interdigitated with the

Different than other surface treatments

Virtually all dental implant surfaces on the market are grit-blasted and/or acid-etched. These manufacturing methods create random

surfaces that vary from point to point on the implant and alter cell reaction depending on where each cell comes in contact with

the surface.10 While random surfaces have shown higher osseointegration than machined surfaces,11 only the Laser-Lok surface has

been shown using light microscopy, polarized light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy to also be effective for soft tissue

attachment.2,12

shop online at www.biohorizons.com

The clinical advantage

Crestal Bone Loss

The Laser-Lok surface has been shown in several studies

to offer a clinical advantage over other implant designs.

In a prospective, controlled multi-center study, Laser-

Lok implants, when placed alongside identical implants

with a traditional surface, were shown at 37 months

post-op to reduce bone loss by 70% (or 1.35mm).4 In a

retrospective, private practice study, Laser-Lok implants placed in a variety of site conditions and followed up to 3

e in Bone Le -2.00

years minimized bone loss to 0.46mm.5 In a prospective, University-based overdenture study, Laser-Lok implants

reduced bone loss by 63% versus NobelReplace™ Select.6

In a 3-year multicenter perspective study, the Laser-Lok surface showed superior bone maintenance over identical implants without the Laser-Lok surface.4

Latest discoveries

The establishment of a physical, connective tissue

Connective

attachment (unlike Sharpey fibers) to the Laser-Lok

surface has generated an entirely new area of research and

development: Laser-Lok applied to abutments. This could provide an opportunity to use Laser-Lok abutments to create a biologic seal and Laser-Lok implants to establish superior osseointegration9 – a solution that offers the best of both worlds. Alternatively, Laser-Lok abutments could

support peri-implant health around implants without

Laser-Lok. In a recent study, Laser-Lok abutments and

standard abutments were randomly placed on implants

Comparative histologies show the biologic differences between standard abutments and Laser-Lok

with a grit-blasted surface to evaluate the differences. In

abutments including changes in epithelial downgrowth, connective tissue and crestal bone health.12

this proof-of-principle study, a small band of Laser-Lok microchannels was shown to inhibit epithelial downgrowth

Standard

and establish a connective tissue attachment (unlike

abutment

at 3 months

at 3 months

Sharpey fibers) similar to Laser-Lok implants.12 In these cases, an epithelial barrier and a supracrestal connective

tissue barrier were created, even when the implants had a machined collar.12 The resulting crestal bone levels were

higher than what was seen with standard abutments and provides some insight into the role soft tissue stability may play in maintaining crestal bone health.

Comparative SEM images show the variation in tissue attachment strength on standard and Laser-Lok abutments when a tissue flap is incised vertically and manually lifted using forceps.12

Laser-Lok Technologyis available on Laser-Lok 3.0, Tapered Internal, Single-stage, Internal implants & abutments

• NobelReplace is a trademark of Nobel Biocare.

shop online at www.biohorizons.com

Histologic Evidence of a Connective Tissue Attachment to Laser

Microgrooved Abutments: A Canine Study

M Nevins, DM Kim, SH Jun, K Guze, P Schupbach, ML Nevins.

Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent , Volume 30, 2010. p. 245-255.

A grit-blasted implant and standard

In a polarized light view, this specimen

In this specimen, regenerated bone

A polarized light image demonstrates

abutment demonstrated apical JE

clearly demonstrates parallel running

was attached to the Laser-Lok

perpendicularly inserting connective

migration, resulting in significant crestal

connective tissue fibers against both the

abutment surface and the IAJ microgap

tissue fibers into the microgrooved

bone resorption.

abutment and implant collar surfaces.

was eliminated.

abutment surface.

In addition, significant crestal bone loss is seen.

ABSTRACTPrevious research has demonstrated the effectiveness of laser-ablated microgrooves placed within implant collars in supporting direct connective tissue attachments to altered implant surfaces. Such a direct connective tissue attachment serves as a physiologic barrier to the apical migration of the junctional epithelium (JE) and prevents crestal bone resorption. The current prospective preclinical trial sought to evaluate bone and soft tissue healing patterns when laser-ablated microgrooves are placed on the abutment. A canine model was selected for comparison to previous investigations that examined the negative bone and soft tissue sequelae of the implant-abutment microgap. The results demonstrate significant improvement in peri-implant hard and soft tissue healing compared to traditional machined abutment surfaces.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThe current study was designed to examine the effects of two different implant and abutment surfaces on epithelial and connective tissue attachment, as well as peri-implant bone levels. Six foxhounds were selected for this study. Each dog received 6 implants in the bilateral mandibular premolar and first molar extraction sites, for a total of 36 implants. The sites were randomly assigned to receive tapered internal implants (BioHorizons) with either resorbable blast texturing (RBT) or RBT with a 0.3mm machined collar. In addition, either machined-surface or Laser-Lok microchannel healing abutments were assigned randomly to each implant. The abutments were placed at the time of surgery.

RESULTSThe presence of the 0.7 mm laser ablated microchanneled zone consistently enabled intense fibroblastic activity to occur on the abutment-grooved surface, resulting in a dense interlacing complex of connective tissue fibers oriented perpendicular to the abutment surface that served as a physiologic barrier to apical JE migration. As a consequence of inhibiting JE apical migration, crestal bone resorption was prevented. Significantly, in two cases bone regeneration coronal to the IAJ and onto the abutment surface occurred, completely eliminating the negative sequelae of the IAJ microgap.

In contrast, abutments devoid of laser-ablated microgrooved surfaces, exhibited little evidence of robust fibroblastic activity at the abutment-tissue interface. A long JE extended along the abutment and implant collar surfaces, preventing formation of the physiologic connective tissue barrier and causing crestal bone resorption. Parallel rather than functionally oriented perpendicular connective tissue fibers apposed the abutment-implant surfaces.

Histologic Evidence of Connective Tissue Integration on Laser Microgrooved

Abutments in Humans

NC Geurs, PJ Vassilopoulos, MS Reddy.

Clinical Advances in Periodontics, Vol. 1, No. 1, May 2011.

Ground section of specimen stained

Higher magnification of Figure 1

Polarized light view of Figure 2

Polarized light view from an area coronal

with toluidine blue/Azur ll. The oral

showing connective tissue in close

demonstrating collagen fibers in a

to Figure 3. The orientation of the

epithelium and junctional epithelium

contact with the microgrooved surface

functional orientation toward the

collagen fibers is more parallel to the

are tapering off coronal to the

of the abutment.

abutment surface.

smooth implant surface.

Human histology and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are presented, outlining the soft tissue integration to a laser microgrooved abutment surface.

CASE PRESENTATION

In two patients, prosthetic abutments with a laser microgrooved surface were placed on osseointegrated implants. After 6 weeks of healing, the abutments and the surrounding soft tissue were removed and prepared for histology and SEM. The most apical epithelium was found coronal to this surface. Connective tissue demonstrated collagen fibers oriented perpendicular to the microgrooved surface. There was intimate contact between the connective tissues and the microgrooved abutment surface.

The abutments in these patients had connective tissue integration with functionally oriented fibers to the microgrooved surface.

Why is this case new information? To our knowledge, this is the first human case series reported with human histology describing the connective tissue attachment around a microgrooved abutment.

What are the keys to successful management in this case? The abutment surface characteristics can lead to connective tissue integration with the microgrooved surface, with functionally oriented collagen fibers.

What are the primary limitations to success in this case? This is only a case series of the histology of the attachment. No clinical outcomes or advantages are reported. Further studies will need to be conducted to demonstrate the clinical advantages.

Connective Tissue Attachment to Laser Microgrooved

Abutments: A Human Histologic Case Report

M Nevins, M Camelo, ML Nevins, P Schupbach, DM KimSubmitted for Publication, Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent

Healing abutments with Laser-Lok microchannels connect to the implant

At 10 weeks, healing is normal for patient #1 with no evidence of infection

fixtures. Mucoperiosteal flaps closed without tension.

or inflammation.

Crestal bone is in close contact with the implant collar surface, with no

At higher power, dense connective tissue is in intimate contact with the

evidence of bone loss apparent, but rather new bone formation.

abutment's Laser-Lok micro-grooved surfaces.

ABSTRACTPrevious preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of precisely configured laser-ablated microgrooves placed on implant collars to allow direct connective tissue attachment to the implant surface. A recent canine study examining laser-ablated microgrooves placed in a defined healing abutment area demonstrated similar findings. In both instances direct connective tissue attachment to the implant/abutment surface served as an obstacle to the apical migration of the junctional epithelium, thus preventing crestal bone resorption. The current case report examined the effectiveness of abutment positioned laser-ablated microgrooves in human subjects. As in the preclinical trial, precisely defined laser-ablated microgrooves allowed direct connective tissue attachment to the altered abutment surface, prevented apical migration of the junctional epithelium and thus protected crestal bone from premature resorption.

Reattachment of the connective tissue fibers to the laser microgrooved

abutment surface

M Nevins, M Camelo, ML Nevins, P Schupbach, DM KimSubmitted for Publication, Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent

Laser microgrooved healing abutments have been placed at

Laser microgrooved healing abutment has been replaced by the

the time of the implant surgery.

laser microgrooved cylindric permanent abutment.

The retrieved specimen demonstrated normal peri-abutment soft tissues, without evidence of an inflammatory cell infiltrate. Polarized light imagery of mesial and distal surfaces revealed dense, obliquely oriented connective tissue fibers attaching directly to the laser microgrooved abutment surfaces.

This report presents human evidence of reattachment of the connective tissue when the laser microgrooved healing abutment has been replaced by the laser microgrooved cylindric permanent abutment. No additional bone loss has been noted 15 weeks after the placement of the laser microgrooved cylindric permanent abutment. A dense connective tissue was in intimate contact with the laser microgrooved surface to the point of the soft tissue separation, and a clear evidence of the junctional epithelium ending at the coronal-most position of the laser microgrooved zone was identified.

Clinical Evaluation of Laser Microtexturing for Soft Tissue and Bone

Attachment to Dental Implants

GE Pecora, R Ceccarelli, M. Bonelli, H. Alexander, JL Ricci.

Best Clinical Innovations Presentation Award. Academy of Osseointegration 2004 Annual Meeting.

Implant Dentistry. Volume 18(1). February 2009. pp. 57-66.

Crestal Bone Loss

Crestal bone loss, Laser-Lok vs. Control for 37 month follow-up. Error bars=standard error; p<0.005 after month 5.

THREE YEAR PROSPECTIVE, C

A tapered dental implant (Laser-Lok [LL] surface treatment) with a 2 mm wide collar, that has been laser micromachined in the lower 1.5 mm to preferentially accomplish bone and connective tissue attachment while inhibiting epithelial downgrowth, was evaluated in a prospective, controlled, multicenter clinical trial.

Data are reported at measurement periods from 1 to 37 months postoperative for 20 pairs of implants in 15 patients. The implants are placed adjacent to machined collar control implants of the same design. Measurement values are reported for bleeding index, plaque index, probing depth, and crestal bone loss.

No statistical differences are measured for either bleeding or plaque index. At all measurement periods there are significant differences in the probing depths and the crestal bone loss differences are significant after 7 months (P<0.001). At 37 months the mean probing depth is 2.30 mm and the mean crestal bone loss is 0.59 mm for LL versus 3.60 and 1.94 mm, respectively, for control implant. Also, comparing results in the mandible versus those in the maxilla demonstrates a bigger difference (control implant - LL) in the mean in crestal bone loss and probing depth in the maxilla. However, this result was not statistically significant.

The consistent difference in probing depth between LL and control implant demonstrates the formation of a stable soft-tissue seal above the crestal bone. LL limited the crestal bone loss to the 0.59 mm range as opposed to the 1.94 mm crestal bone loss reported for control implant. The LL implant was found to be comparable with the control implant in safety endpoints plaque index and sulcular bleeding index. There is a nonstatistically significant suggestion that the LL crestal bone retention superiority is greater in the maxilla than the mandible.

7 year follow-up

Laser-Lok (LL) and non Laser-Lok (C) at time

Laser-Lok (LL) and non Laser-Lok (C) at 7

The Effects of Laser Microtexturing of the Dental Implant Collar on

Crestal Bone Levels and Peri-implant Health

S Botos, H Yousef, B Zweig, R Flinton, S Weiner.

Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2011;26:492-498.

TI-UNIT VERSUS NOBELREPL

Implant placement protocol with two implants loaded and two implants unloaded.

Probing Depths (12 months)

Unloaded (12 months)

Loaded (12 months)

tal Bone L

tal Bone L

At 12-months, the Laser-Lok implants had a mean probing

Average crestal bone loss of unloaded Laser-Lok implants

Average crestal bone loss of loaded Laser-Lok implants

depth of 0.43mm versus 1.64mm for NobelReplace Select

was 0.29mm versus 0.55mm for NobelReplace Select

was 0.42mm versus 1.13mm for NobelReplace Select

(p<= 0.001).

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Polished and machined collars have been advocated for dental implants to reduce plaque accumulation and crestal bone loss. More

recent research has suggested that a roughened titanium surface promotes osseointegration and connective tissue attachment. The purpose of

this research was to compare crestal bone height adjacent to implants with laser-microtextured and machined collars from two different implant

systems (Laser-Lok and Nobel Replace Select).

Materials and Methods: Four implants, two Laser-Lok and two Nobel Replace Select, were placed in the anterior mandible to serve as

overdenture abutments. They were placed in alternating order, and the distal implants were loaded with ball abutments. The mesial implants were

left unloaded. The distal implants were immediately loaded with prefabricated dentures. Plaque Index, Bleeding Index, and probing depths (PDs)

were measured after 6 and 12 months for the loaded implants. Bone loss for both groups (loaded and unloaded) was evaluated via standardized

radiographs.

Results: Plaque and bleeding values were similar for both implant types. The Laser-Lok implants showed shallower PDs (0.36 ± 0.5 mm and

0.43 ± 0.51 mm) than those Nobel Replace Select (1.14 ± 0.77 mm and 1.64 ± 0.93 mm; P < .05 for 6 and 12 months, respectively). At 6 and 12

months, respectively, the Laser-Lok implants showed less crestal bone loss for both loaded (0.19 ± 0.15 mm and 0.42 ± 0.34 mm) and unloaded

groups (0.15 ± 0.15 mm and 0.29 ± 0.20 mm) than the Nobel Replace Select implants for both the loaded (0.72 ± 0.5 mm and 1.13 ± 0.61 mm)

and unloaded groups (0.29 ± 0.28 mm and 0.55 ± 0.32 mm).

Conclusion: Laser-Lok implants resulted in shallower PDs and less peri-implant crestal bone loss than that seen around Nobel Replace Select.

• NobelReplace is a trademark of Nobel Biocare.

Long-term case studies using a Laser-Lok implant

Courtesy of Cary Shapoff, DDS (Fairfield, CT)

Restorations by Jeffrey A. Babushkin, DDS (Trumbull, CT)

Numerous published animal and human dental implant studies report crestal bone loss from the time of placement of the healing abutment

to various time periods after restoration. The bone loss can result in loss of interproximal papilla and recession of crown margins. These two case reports demonstrate the long-term results that can be obtained utilizing implants with the Laser-Lok microchannel collar design to preserve crestal bone and soft tissue esthetics. Case 1 involved extraction, socket grafting, 6 month delayed implant placement and final restoration in 6 months. Case 2 involved extraction, immediate implant placement with simultaneous grafting and provisional crown placement two months later.

Bone defect immediately following extraction

Tooth #9 prior to extraction

A 34 year old female presented with external resorption at the level of the CEJ of tooth #9. Various treatment options were presented and the patient elected extraction and dental implant placement. After atraumatic extraction, the socket anatomy did not allow for immediate placement with acceptable initial stability. The socket was grafted with allograft calcified bone and allowed to heal for 6 months. At that time a dental implant with Laser-Lok microchannel collar design was placed. A subepithelial connective tissue graft was also utilized on the adjacent tooth #10 for root coverage. Six months after placement second stage surgery was performed and the tooth was restored with a customized abutment and PFM crown. Note the maintenance of excellent crestal bone levels (within 0.5mm of the implant/abutment interface) at 10 years post-restoration. The soft tissue margins have remained stable and exhibit excellent periodontal health.

Laser-Lok implant at 8 years post-restoration

Laser-Lok implant at time of placement

Bone levels maintained at 10 years post-restoration

Tooth #9 with chronic infection

Tooth #9 extracted showing clinical defect

Esthetics at 4 years post-restoration

Laser-Lok implant at time of placement

Bone levels at 4 years post-restoration

This 60 year old female presented with chronic infection evidenced by a fistula at the apical extent of tooth #9. This tooth had previously been treated with root canal and apical surgery. All treatment options were reviewed with the patient and dental implant replacement was chosen. Because the patient was relocating to South America for a period of two years, immediate extraction, dental implant placement with socket grafting was performed. The dental implant was a 5 mm x 13 mm Laser-Lok microchannel collar design. A provisional crown was placed 2 months following implant placement. The patient had no other professional dental care for two years and upon returning home, the final crown was placed. Note the crestal bone levels (within 0.5 mm of the abutment/implant interface) at fours years after implant loading.

These two cases demonstrate the ability of the Laser-Lok microchannel collar design to maintain crestal bone levels and soft tissue esthetics around dental implants. Both cases involved implant placement in grafted sites. Both cases demonstrate unequivocal clinical and radiographic evidence of crestal bone stability in close proximity to the abutment/implant interface (micro-gap). A traditional expectation of bone loss below the collar and to the first thread was not noted. The ability of the Laser-Lok microchannels to maintain crestal bone and provide supracrestal connective tissue attachment may create a new definition of "normal" implant biologic width.

Radiographic Analysis of Crestal Bone Levels Around Laser-Lok

Collar Dental Implants

CA Shapoff, B Lahey, PA Wasserlauf, DM Kim.

Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2010;30:129-137

Failed bridge prior to implant placement. 4-5mm ridge required

Healing abutments placed at 3.5 months. Crestal bone adjacent

At three years, stable crestal bone adjacent to Laser-Lok

ridge splitting at implant placement.

to Laser-Lok collar.

collar with no indication of bone loss to the first thread.

INTRODUCTIONThis retrospective radiographic study was organized to evaluate the clinical efficacy of implants with Laser-Lok microtexturing (8- and 12-µm grooves). A physical attachment of connective tissue fibers to the Laser-Lok microtexturing on the implant collar has been previously demonstrated using human histology, polarized light microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy. This analysis of 49 implants demonstrated a mean crestal bone loss of 0.44 mm at 2 years postrestoration and 0.46 mm at 3 years. All bone loss was contained within the height of the collar, and no bone loss was evident to the level of the implant threads. The radiographic evaluation of the clinical application of this implant supports previous findings that establishing a biologic seal of connective tissue fibers around a dental implant may be clinically relevant.

oss (mm) 0.40

tal Bone L

res

C 0.20

This analysis of 49 implants demonstrated a mean crestal bone loss of 0.44 mm at 2 years postrestoration and 0.46 mm at 3 years.

Human Histologic Evidence of a Connective Tissue Attachment to a Dental Implant

M Nevins, ML Nevins, M Camelo, JL Boyesen, DM Kim.

The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. Volume 28, Number 2, 2008.

ONNECTIVE TISSUE A

This human proof-of-principle study was designed to investigate the possibility of achieving a physical connective tissue attachment to the Laser-Lok microchannel collar of a dental implant. Its 2-mm collar has been micromachined to encourage bone and connective tissue attachment while preventing apical migration of the epithelium. Implants were harvested with the surrounding implant soft and hard tissues after 6 months. The histologic investigation was conducted with light microscopy, polarized light, and scanning electron microscopy.

The implants were osseointegrated with histologic evidence of direct bone contact. There was a connective tissue attachment to the Laser-Lok microchannels. There were no signs of inflammation. The peri-implant tissues consisted of a dense, collagenous lamina propria covered with a stratified, squamous, keratinizing oral epithelium. The latter was continuous with the parakeratinized sulcular epithelium that lined that lateral surface of the peri-implant sulcus. Apically, the sulcular epithelium overlapped the coronal border of the junctional epithelium. The sulcular epithelium was continuous with the junctional epithelium, which provided epithelial union between the implant and the surrounding

peri-implant mucosa. Between the apical termination of the junctional epithelium and the alveolar bone crest, connective tissue directly apposed the implant surface.

Light microscopic evaluation of these specimens revealed intimate contact of the junctional epithelial cells with the implant surface. The

microgrooved area of the implants was covered with connective tissue. Polarized light microscopy of this area revealed functionally oriented collagen fibers running toward the grooves of the implant surface. SEM of a corresponding area of the specimen confirmed the presence of attached collagen fibers.

All specimens demonstrated a high degree of bone-to-implant contact and intense remodeling activity. In specimens that showed collagen fibers functionally oriented toward the grooves on the implant surface, remodeling of new bone in the coronal direction was observed. SEM revealed sulcular epithelium with the desquamating activity of the cells and the junctional epithelium. It appears that the connective tissue attachment is instrumental in preserving the alveolar bone crest and inhibiting apical migration of the epithelium.

High magnification identifies the apical extent of the

SEM showing collagen fibers attached to the rough

Micro CT image showing an overview of osseointegration and

junctional epithelium. There is then a connective tissue

implant surface.

the bone-to-implant contact (in red). Note that the level of

attachment to the laser microchannel surface that extends

bone contact extends to cover all threads of the implant and

to the point of bone attachment.

corresponds to the histologic observations. This supports the value of the connective tissue attachment to prevent loss of crestal bone.

Hard and Soft Tissue Changes After Crestal and Subcrestal Immediate

Implant Placement

RU Koh, TJ Oh, I Rudek, GF Neiva, CE Misch, ED Rothman, HL Wang

J Periodontol 2011;82:1112-1120.

Placement level and clinical measurements. A) Crestal placement. B) Subcrestal placement. C) Facial tissue thickness. D) Facial plate thickness. E) Palatal plate thickness. F) MBL. G) TE. H) HDD. I) T-I.

The purpose of this study is to assess the influence of the placement level of implants with a laser-microtextured collar design on the outcomes of crestal bone and soft tissue levels. In addition, we assessed the vertical and horizontal defect fill and identified factors that influenced clinical outcomes of immediate implant placement.

Twenty-four patients, each with a hopeless tooth (anterior or premolar region), were recruited to receive dental implants. Patients were randomly assigned to have the implant placed at the palatal crest or 1mm subcrestally. Clinical parameters including the keratinized gingival (KG) width, KG thickness, horizontal defect depth (HDD), facial and interproximal marginal bone levels (MBLs), facial threads exposed, tissue–implant horizontal distance, gingival index (GI), and plaque index (PI) were assessed at baseline and 4 months after surgery. In addition, soft tissue profile measurements including the papilla index, papilla height (PH), and gingival level (GL) were assessed after crown placement at 6 and 12 months post-surgery.

The overall 4-month implant success rate was 95.8% (one implant failed). A total of 20 of 24 patients completed the study. At baseline, there were no significant differences between crestal and subcrestal groups in all clinical parameters except for the facial MBL (P = 0.035). At 4 months, the subcrestal group had significantly more tissue thickness gain (keratinized tissue) than the crestal group compared to baseline. Other clinical parameters (papilla index, PH, GL, PI, and GI) showed no significant differences between groups at any time. A facial plate thickness <=1.5 mm and HDD >=2 mm were strongly correlated with the facial marginal bone loss. A facial plate thickness <=2 mm and HDD >=3 were strongly correlated with horizontal dimensional changes.

The use of immediate implants was a predictable surgical approach (96% survival rate), and the level of placement did not influence horizontal and vertical bone and soft tissue changes. This study suggests that a thick facial plate, small gaps, and premolar sites were more favorable for successful implant clinical outcomes in immediate implant placement.

Histologic Evaluation of 3 Retrieved Immediately Loaded Implants After a

4-Month Period

I Giovanna, G Pecora, A Scarano, V Perrotti, A Piattelli.

Implant Dentistry. Vol 15, Number 3, 2006.

Figure 3. The definitive and provisional implants have been inserted.

Figure 4. At low power magnification, it is possible to see that mainly lamellar bone is in contact with the implant surface. Few marrow spaces are present. The first bone to implant contact is above the level of the first thread. No areas of resorption are present at the tip of the threads (acid fushin and toluidine blue, original magnification x12).

Objective: To perform a histologic and histomorphometric analysis of the peri-implant tissue reactions and bone-titanium interface in 3

immediately loaded (provisional loaded) titanium implants retrieved from a man after a loading period of 4 months.

Materials & Methods: A 35 year-old patient with a maxillary partial edentulism did not want to wear a provisional removable prosthesis

during the healing period. It was decided to insert 3 definitive implants and use 3 provisional implants for the transitional period. The

provisional implants were loaded the same day with a resin prosthesis in occlusal contact. During the second surgical phase, after 4 months,

the provisional prosthesis was removed, and the provisional implants were retrieved with a trephine bur. Before retrieval, all implants

appeared to be clinically osseointegrated. The specimens were processed for observation under light microscopy.

Results: At low magnification, it was possible to observe that bone trabeculae were present around the implant. Areas of bone remodeling

and haversian systems were present near the implant surface. Under polarized-light microscopy, it was possible to observe that in the

coronal aspect of the thread, the lamellar bone showed lamellae that tended to run parallel to the implant surface, while in the inferior

aspect of the thread, the bone lamellae ran perpendicular to the implant surface.

Histologic evaluation of a provisional implant retrieved from man 7 months after

placement in a sinus augmented with calcium sulphate: a case report

G Iezzi, E Fiera, A Scarano, G Pecora, A Piattelli.

Journal of Oral Implantology. Volume 33, No. 2. 2007.

ADED SINUS AOY LTEL

Figures 7–12. Figure 7. At low-power magnification, it is possible to see that bone is present around and in contact with the implant. The line divides native bone from newly formed bone (A) Native bone. (B) Newly formed bone. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X12). FIGURE 8. Higher magnification of Figure 7 (area A). Newly formed trabecular bone with large osteocyte lacunae was present close to the implant surface. No residual calcium sulphate is present. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X50). FIGURE 9. Higher magnification of Figure 7 (area A). Cortical mature bone is present near the implant surface, and bone undergoing remodeling is in direct contact with the implant surface. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X100). FIGURE 10. Higher magnification of Figure 7 (area B). High magnification of the coronal portion of the bone–implant interface. Active osteoblasts secreting osteoid matrix are present. No biomaterial is present. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X100). FIGURE 11. Higher magnification of Figure 7 (area B). Newly formed bone in close contact with the implant surface. Wide marrow spaces are present. No calcium sulphate is present. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X50). FIGURE 12. Higher magnification of Figure 7 (area B). Osteoblasts (arrows) secreting osteoid matrix are observed in the apical portion of the implant. (Acid fuchsin and toluidine blue, magnification X400).

Little is known about the in vivo healing processes at the interface of implants placed in different grafting materials. For optimal sinus augmentation, a bone graft substitute that can regenerate high-quality bone and enable the osseointegration of load-bearing titanium implants is needed in clinical practice. Calcium sulphate (CaS) is one of the oldest biomaterials used in medicine, but few studies have addressed its use as a sinus augmentation material in conjunction with simultaneous implant placement. The aim of the present study was to histologically evaluate an immediately loaded provisional implant retrieved 7 months after simultaneous placement in a human sinus grafted with CaS. During retrieval, bone detached partially from one of the implants which precluded its use for histologic analysis. The second implant was completely surrounded by native and newly formed bone, and it underwent histologic evaluation. Lamellar bone, with small osteocyte lacunae, was present and in contact with the implant surface. No gaps, epithelial cells, or connective tissues were present at the bone–implant interface. No residual CaS was present. Bone–implant contact percentage was 55% ± 8%. Of this percentage, 40% was represented by native bone and 15% by newly formed bone. CaS showed complete resorption and new bone formation in the maxillary sinus; this bone was found to be in close contact with the implant surface after immediate loading.

Immediate Implant Placement and Provisionalization—Two Case Reports

SJ Froum, SC Cho, H Francisco, YS Park, N Elian, D Tarnow.

Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2007;19(10):421-428.

ACEMENT IN THE ES

Figure 1. Preoperative appearance of the FPD from the right canine to the right central

Figure 2A. Radiographic appearance of the

incisor replacing the missing lateral incisor.

implants immediately following placement.

Figure 3. Postoperative appearance 2.5 years following implant placement demonstrates

Figure 2B. Postoperative appearance 2.5

aesthetic maintenance of the buccogingival marginal levels.

years following implant loading. Note the maintenance of the interproximal bone levels.

Endosseous dental implants have traditionally been placed using a two-stage surgical procedure with a 6- to 12-month healing period following tooth extraction. In order to decrease healing time, protocols were introduced that included immediate implant placement and provisionalization following tooth extraction. Although survival rates for this technique are high, postoperative gingival shrinkage and bone resorption in the aesthetic zone are potential limitations. The two case reports described herein present a surgical technique for the preservation of anterior aesthetics that combines minimally invasive extraction, immediate implant placement, provisionalization, and the use of implants with a laser micro-grooved coronal design.

The use of implants with a laser microgrooved coronal design may have contributed to the maintenance of buccal soft tissue, providing attachment and preventing epithelial cell downgrowth, which often occurs with machined collar implants. Maintenance of this supra crestal soft tissue often depends on its ability to establish an attachment supercrestally to the implant surface.

Influence of a microgrooved collar design on soft and hard tissue healing of

immediate implantation in fresh extraction sites in dogs

SY Shin, DH Han

Clin. Oral Impl. Res. 21, 2010; 804–814.

Fig. 1. Schematic drawing describing the different landmarks between which histometric measurements were

Fig. 2. Micrographs showing longitudinal section of microgrooved

performed. (a) Microgrooved collar implant group; (b) turned collar implant group. aBE, apical termination of the

groups (a) and turned surface groups (b) after 12 weeks of healing. B,

barrier epithelium; B/I, marginal level of bone-to-implant contact; C, marginal level of the bone crest; PM, margin

buccal wall; L, lingual wall; I, implant; PM, peri-implant mucosa. H-E

of the peri implant mucosa; M, marginal level of the microgrooved surface or machined surface of implant.

staining; original magnification x 10.

Fig. 3. Fluorescent images under polarizing microscope showing longitudinal section

Fig. 4. Fluorescent images showing longitudinal section of microgrooved group (a) and

of microgrooved group (a) and turned surface group (b) after 12 weeks of healing.

turned surface group (b) after 12 weeks of healing. The arrows indicate the apical level of

The solid arrows indicate the collagen fiber direction which are parallel to the implant

the junctional epithelium. CT, connective tissue; I, implant. Original magnification x 50.

surface over the turned surface and the dotted arrows point the collagen fibers perpendicular to the implant over the 8mm pitch microgrooved surface. CT, connective tissue; I, implant. Original magnification x 200.

Objective: This study compared the alveolar bone reduction after immediate implantation using microgrooved and smooth collar implants in

fresh extracted sockets.

Materials and Methods: Four mongrel dogs were used in this study. The full buccal and lingual mucoperiosteal flaps were elevated and

the third and fourth premolars of the mandible were removed. The implants were installed in the fresh extracted sockets. The animals were

sacrificed after a 3-month healing period. The mandibles were dissected and each implant site was removed and processed for a histological

examination.

Results: During healing, the marginal gaps in both groups, which were present between the implant and the socket walls at implantation,

disappeared as a result of bone filling and resorption of the bone crest. The buccal bone crests were located apical of its lingual counterparts.

At the 12-week interval, the mean bone–implant contact in the microgrooved collar group was significantly higher than that of the turned collar

group. From the observations in some of the microgrooved collar groups, we have found bone attachment to the 12 mm microgrooved surface

and collagen fibers perpendicular to the long axis of the implants over the 8 mm microgrooved surface.

Conclusion: Within the limitations of this study, microgrooved implants may provide more favorable conditions for the attachment of hard and

soft tissues and reduce the level of marginal bone resorption and soft tissue recession.

Mechanical basis for bone retention around dental implants

H Alexander, JL Ricci, GJ HricoJ Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. Volume 88B, Issue 2, Pages 306-311, Feb 2009.

Figure 1. Max stress of 91.9 MPa seen in Control implant (left) and 22.6 MPa seen in Laser-Lok implant (right) from 80 Newton side load.

Figure 2. Summary of the results of Finite Element Analysis demonstrating the stress decrease resulting from implant attachment.

This study, analytically, through finite element analysis, predicts the minimization of crestal bone stress resulting from implant collar surface treatment. A tapered dental implant design with Laser-Lok (LL) and without (control, C) laser microgrooving surface treatment are evaluated. The LL implant has the same tapered body design and thread surface treatment as the C implant, but has a 2-mm wide collar that has been laser micromachined with 8 and 12µm grooves in the lower 1.5 mm to enhance tissue attachment. In vivo animal and human studies previously demonstrated decreased crestal bone loss with the LL implant. Axial and side loading with two different collar/bone interfaces (nonbonded and bonded, to simulate the C and LL surfaces, respectively) are considered. For 80 N side load, the maximum crestal bone distortional stress around C is 91.9 MPa, while the maximum crestal bone stress around LL, 22.6 MPa, is significantly lower. Finite element analysis suggests that stress overload may be responsible for the loss of crestal bone. Attaching bone to the collar with LL is predicted to diminish this effect, benefiting crestal bone retention.

Marginal Tissue Response to Different Implant Neck Design

HEK Bae, MK Chung, IH Cha and DH Han.

Yonsei University College of Dentistry, Seoul, South KoreaJ Korean Acad Prosthodont. 2008 Dec;46(6):602-609.

Purpose: This animal study examined the histomorphometric variations between a turned neck (TN) implant with a RBM body, a micro-

threaded (MT) neck implant and a micro-grooved (MG) implant (Laser-Lok).

Materials and Methods: Mandibular premolars from four mongrel dogs were removed and left to heal for three months. One of three

different implant systems were placed according to the manufacturers' protocol and left submerged for 8 and 12 weeks. These were then harvested for histological examination. All specimens have shown uneventful healing for the duration of the experiment.

Results: The histological slides have shown that all samples osseointegrated successfully with active bone remodeling adjacent to

the implants. With the Laser-Lok implants, 0.40mm and 0.26mm of marginal bone loss was observed at 8 and 12 weeks respectively.

The micro-threaded implants had changes of 0.79mm and 0.56mm. The machined neck implants had marginal bone level changes of

1.61mm and 1.63mm in the 8 and 12 week specimens. A complex soft tissue arrangement was observed against micro-threaded and

micro-grooved implants.

Conclusions: This is an animal study which looked at the marginal bone level and the soft tissue reaction between different implant

systems with various neck designs. Within the limitation of this animal study the following statement can be concluded;

1. A clear morphometric difference in the bone area could not be noticed between MT and MG implant neck types.

2. The BIC in MG implants were slightly higher than corresponding healing times of MT and TN implants. Higher values of the BIC could

be measured in week 12 specimens than in week 8 specimens. 3. In the marginal bone level, there was marked lowering with the TN implants and least with MG implants from the reference point.

There were higher marginal bone levels in week 12 than week 8 in MT and MG implants specimens but with minimal differences in TN implant specimens.

4. With MT and MG implant surfaces, the collagen alignments were not parallel to the long axis of the implants. The MT and MG implants,

especially MG implants had advantageous tissue response in comparison to the turned neck implants.

Table 1. Histomorphometric measurements of three different implants

Implant type Weeks

Marginal bone loss / mm

Bone area in threads / mm

A. Turned neck implant with RBM body

B. Micro-thread implant

C. Laser-Lok implant

The Effects of Laser Microtextured Collars Upon Crestal Bone Levels of

Dental Implants

S Weiner, J Simon, DS Ehrenberg, B Zweig, and JL Ricci.

Implant Dentistry, Volume 17, Number 2, 2008. p. 217-228.

Table 1. Nonparametric Histomorphometric Analysis Data (±Standard Error)

ONNECTIVE TISSUE A

3-mo loaded specimens 1.50±0.29

(8 sections from 3

implants)Laser micromachined

(6 sections from 4

implants)6-mo loaded specimens 1.75±0.22

Control/smooth (12

interfaces)Laser micromachined

Figures 1A (left), 1B (middle), 1C (right). Light photomicrographs of epithelial and

Figure 3 Scanning electron photomicrograph (backscattered

soft connective tissue interaction with experimental (1A and 1B) and control (1C)

electron imaging model) of bone integration of an experimental

surfaces at 6 months (3 months after loading). An epithelial layer is seen in the upper

implant at 3 months (uncovering). Left: Overview (collage)

portion of Fig.1A which ends in a burst of epithelial cells that are attached at the

of several images showing bone integration of the body of

edge of the laser-micromachined region (center of photo). The lower part of Fig. 1A

the implant as well as direct bone integration of the laser-

and all of Fig. 1B show connective attachment to the laser-micromachined surfaces.

micromachined collar. Right: Higher magnification of bone

Fig. 1C shows soft tissue downgrowth between the bone and implant interface in a

integration of the implant body. Thread pitch = 1 mm.

control implant.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to examine the crestal bone, connective tissue, and epithelial cell response to a laser microtextured

collar compared with a machined collar, in the dog model.

Materials: Six mongrel dogs had mandibular premolars and first molars extracted and after healing replaced with BioLok implants 4x8 mm.

Each dog had 3 control implants placed on one side of the mandible and 3 experimental, laser microtextured, implants placed contralaterally.

After 3 months, 1 dog was killed. Bridges were placed on the implants of 4 of the dogs. The sixth dog served as a negative control for the

duration of the experiment. Two of the dogs were killed 3 months after loading, two of the dogs were killed 6 months after loading as was the

negative (unloaded) control. Histology, electron microscopy, and histomorphometric analysis was done on histologic sections obtained from

block sections of the mandible containing the implants.

Results: Initially the experimental implants showed greater bone attachment along the collar. With time the bone heights along the control

and experimental collars were equivalent. However, the controls had more soft tissue downgrowth, greater osteoclastic activity, and increased

saucerization compared with sites adjacent to experimental implants. There was closer adaptation of the bone to the laser microtextured

collars.

Conclusion: Use of tissue engineered collars with microgrooving seems to promote bone and soft tissue attachment along the collar and

facilitate development of a biological width.

Connective-tissue responses to defined biomaterial surfaces. I. Growth of rat

fibroblast and bone marrow cell colonies on microgrooved substrates

JL Ricci, JC Grew, H AlexanderJournal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 85A: 313–325, 2008.

TION AND OSSEOINTEGR

Light micrograph of RTF colonies grown for 4 days on control and 6-µm microgrooved substrates. The colony grown on the control substrate (a) displays radial outgrowth from the initial collagen gel ‘‘dot'' seen as the

dark area in the center of the colony. The extent of colony outgrowth can also be seen. The original gel dot is 2 mm in diameter. The colony grown on the 6-µm microgrooved substrate (b) displays extensive outgrowth from the initial gel dot in the direction parallel with the direction of the microgrooves. Less extensive outgrowth is observed in the direction perpendicular to the direction of the microgrooves. This microgroove dimension is below the resolution limit of the microscope at this magnification. Bar = 1 mm (a and b).

Light micrograph of RTF colonies grown for 4 days on control and 6-µm microgrooved substrates. The colony grown on the control substrate (a) displays radial outgrowth from the initial collagen gel ‘‘dot'' seen as the dark area in the center of the colony. The colony grown on the 6-µm microgrooved substrate (b) displays extensive outgrowth from the initial gel dot in the direction parallel with the direction of the microgrooves. Bar = 100 µm (a and b).

Surface microgeometry plays a role in tissue implant surface interactions, but our understanding of its effects is incomplete. Substrate microgrooves strongly influence cells in vitro, as evidenced by contact guidance and cell alignment. We studied ‘‘dot'' colonies of primary fibroblasts and bone marrow cells that were grown on titanium-coated, microgrooved polystyrene surfaces that we designed and produced. Rat tendon fibroblast and rat bone marrow colony growth and migration varied (p < 0.01) by microgroove dimension and slightly by cell type. We observed profoundly altered morphologies, reduced growth rates, and directional growth in colonies grown on microgrooved substrates, when compared with colonies grown on flat, control surfaces (p < 0.01). The cells in our colonies grown on microgrooved surfaces were well aligned and elongated in the direction parallel to the grooves and colonies. Our ‘‘dot'' colony is an easily reproduced, easily measured and artificial explant model of tissue-implant interactions that better approximates in vivo implant responses than culturing isolated cells on biomaterials. Our results correlate well with in vivo studies of titanium dioxide-coated polystyrene, titanium, and titanium alloy implants with controlled microgeometries. Microgrooves and other surface features appear to directionally or spatially organize cells and matrix molecules in ways that contribute to improved stabilization and osseointegration of implants.

Connective-tissue responses to defined biomaterial surfaces. II. Behavior of rat

and mouse fibroblasts cultured on microgrooved substrates

JC Grew, JL Ricci, H Alexander

Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 85A: 326-335, 2008.

Scanning electron micrograph of a portion of a silicon-wafer mold bearing 12-µm microgrooves. Bar = 100 µm.

Scanning-electron micrographs of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts grown on 8- (a) and 12-µm (b) microgrooved substrates for 8 days. The individual cell grown on 8-µm grooves is attached to several adjacent ridges, bridging the intervening grooves. The cells grown on 12-µm grooves most frequently lie atop the ridges or within the grooves. Both microgroove dimensions impose a strong orientation effect upon the cells. Bar = 10 µm.

Surface microgeometry strongly influences the shapes, orientations, and growth characteristics of cultured cells, but in-depth, quantitative studies of these effects are lacking. We investigated several contact guidance effects in cells within ‘‘dot'' colonies of primary fibroblasts and in cultures of a transformed fibroblast cell line, employing titanium-coated, microgrooved polystyrene surfaces that we designed and produced. The aspect ratios, orientations, densities, and attachment areas of rat tendon fibroblasts (RTF) colony cells, in most cases, varied (p < 0.01) by microgroove dimension. We observed profoundly altered cell morphologies, reduced attachment areas, and reduced cell densities within colonies grown on microgrooved substrates, compared with cells of colonies grown on flat, control surfaces. 3T3 fibroblasts cultured on microgrooved surfaces demonstrated similarly altered morphologies. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that microgrooves alter the distribution and assembly of cytoskeletal and attachment proteins within these cells. These findings are consistent with previous results, and taken together with the results of our in vivo and cell colony growth studies, enable us to propose a unified hypothesis of how microgrooves induce contact guidance.

Osseointegration on metallic implant surfaces: effects of microgeometry and

growth factor treatment

SR Frenkel, J Simon, H Alexander, M Dennis, JL Ricci.

J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63(6):706-13.

% Bone ing

ATION AND HIGHER BONE INGRO

Time (weeks)

Figure 1. Percentage of bone ingrowth into channels at 6 and 12 weeks.

Orthopedic implants often loosen due to the invasion of fibrous tissue. The aim of this study was to devise a novel implant surface that would speed healing adjacent to the surface, and create a stable interface for bone integration, by using a chemoattractant for bone precursor cells, and by controlling tissue migration at implant surfaces via specific surface microgeometry design. Experimental surfaces were tested in a canine implantable chamber that simulates the intramedullary bone response around total joint implants. Titanium and alloy surfaces were prepared with specific microgeometries, designed to optimize tissue attachment and control fibrous encapsulation. TGFß, a mitogen

and chemoattractant (Hunziker EB, Rosenberg LC. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:721-733) for osteoprogenitor cells, was used to recruit progenitor cells to the implant surface and to enhance their proliferation. Calcium sulfate hemihydrate (CS) was the delivery vehicle for TGFß; CS resorbs rapidly and appears to be osteoconductive. Animals were sacrificed at 6 and 12 weeks postoperatively. Results indicated that TGFß

can be reliably released in an active form from a calcium sulfate carrier in vivo. The growth factor had a significant effect on bone ingrowth into implant channels at an early time period, although this effect was not seen with higher doses at later periods. Adjustment of dosage should render TGFß more potent at later time periods. Calcium sulfate treatment without TGFß resulted in a significant increase in bone ingrowth throughout the 12-week time period studied. Bone response to the microgrooved surfaces was dramatic, causing greater ingrowth in 9 of the 12 experimental conditions. Microgrooves also enhanced the mechanical strength of CS-coated specimens. The grooved surface was able to control the direction of ingrowth. This surface treatment may result in a clinically valuable implant design to induce rapid ingrowth and a strong bone-implant interface, contributing to implant longevity.

Interactions between MC3T3-E1 cells and textured Ti6Al4V surfaces

Soboyejo WO, Nemetski B, Allameh S, Marcantonio N, Mercer C, Ricci J. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002 Oct; 62(1):56-72.

Figure 1. Extracellular matrix formation after 9 days of cell culture on (a) 12-µm microgrooved substrate; (b) 8-µm microgrooved substrate; (c) Al O -blasted surfaces;

and (d) smooth surfaces.

This paper presents the results of an experimental study of the interactions between MC3T3-E1 (mouse calvarian) cells and textured Ti6Al4V surfaces, including surfaces produced by laser microgrooving; blasting with alumina particles; and polishing. The multiscale interactions between MC3T3-E1 cells and these textured surfaces are studied using a combination of optical scanning transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy. The potential cytotoxic effects of microchemistry on cell-surface interactions also are considered in studies of cell spreading and orientation over 9-day periods. These studies show that cells on microgrooved Ti6Al4V geometries that are 8 or 12 micron deep undergo contact guidance and limited cell spreading. Similar contact guidance is observed on the surfaces of diamond-polished surfaces on which nanoscale grooves are formed due to the scratching that occurs during polishing. In contrast, random cell orientations are observed on alumina-blasted Ti6Al4V surfaces. The possible effects of surface topography are discussed for scar-tissue formation and improved cell-surface integration.

Tissue Response to Transcutaneous Laser Microtextured Implants

CL Ware, JL Simon, JL Ricci.

Presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials. April 24-27, 2002. Tampa, FL.

Figure 1. (A) Scanning electron micrograph

(SEM) of the surface of a laser microtextured

implant. The microtexturing is in two bands

on the two millimeter-wide collar. (B) Higher

magnification SEM of the laser microtextured

surface showing 12µm grooves and ridges

(bar = 40µm).

TABLE SOFT TISSUE INTERF

Introduction: This report describes the use of laser-microtextured transcutaneous implants in a rabbit calvarial model to enhance soft

tissue integration. Dental and orthopaedic implants are routinely microtextured to enhance tissue integration. Computer-controlled laser

microtexturing techniques that produce microgrooved surfaces with defined 8-12µm features on controlled regions of implant surfaces have been developed based on results from cell culture experiments and in vivo models. These textures have been replicated onto the collars of dental implants to provide specific areas for both osteointegration and the formation of a stable soft tissue-implant interface. The objective of this study is to evaluate these implants in a transcutaneous rabbit calvarial model to determine whether controlled laser microtexturing can be used to create a stable interface with connective tissue and epithelium.

Methods: Laser microtextures were produced on the 4mm diameter collars of modified dental implants designed for rabbit studies (Figure 1).

The implants were 4.5mm in length and the threaded portion was 3.75mm in diameter. Implants were produced and supplied by Orthogen

Corporation (Springfield, NJ) and BioLok International (Deerfield Beach, FL). The implant surfaces were modified by ablation of defined

areas, using an Excimer laser and large-area masking techniques. Controlled laser ablation allows accurate fabrication of defined surface

microstructure with resolution in the micron scale range. Laser machined surfaces contained 8µm and 12µm microgrooved systems oriented circumferentially on the collars. The collars of the control implants were "as machined", and were characterized by small machining marks on their surfaces. All implants were cleaned and passivated in nitric acid prior to sterilization.

Four transcutaneous implants were surgically implanted bilaterally in the parietal bones in each rabbit using single-stage procedures. The

surgical protocol was similar to dental implant placement. An incision was made over the sagittal suture, and the skin and soft tissues were

reflected laterally. Implants were placed using pilot drills and fluted spade drills to produce 3.4mm sites for the 3.75mm diameter implants.

The implants were placed with the threaded portion in bone, and the laser-microtextured collar penetrating the subcutaneous soft tissue and

epithelium. Each rabbit received two implants on either side of the midline (1 control and 3 experimental implants per subject). The skin was

then sutured over the implants. Punch openings were made to expose the tops of the platforms of the implants, and the cover screws were

used to fasten down small plastic washers coated with triple antibiotic ointment. The plastic washers were used to prevent the skin from

closing over the implant during the swelling that occurred during early healing. They were removed after two weeks. Twelve rabbits were used

in the study. Rabbits were sacrificed at 2, 4 and 8 weeks, and the implants and surrounding tissues were processed for histology. Hard and

soft tissue response to the implants was examined histologically.

Results and Discussion: No complications or infections were encountered during the course of the experiment. The 2 and 4 week histology

displayed immature soft tissue formations around all implants, and little epithelial interaction with the implant surfaces was noted as the

epithelium had not regenerated at the implant surface by 2 weeks, and no clear relationship between epithelium and implant was seen at 4

weeks. 8-week samples showed more mature soft tissue and epithelial tissue. In these samples, the epithelium had fully regenerated and the

soft tissue showed more mature and organized collagen. In the control samples, the epithelium consistently grew down the interface between

implant and soft tissue and formed a deep sulcus along the implant collar. This sulcus extended to the bone surface and there was little or

no direct soft tissue interaction or integration with the control surfaces. The 8-week laser machined implants produced a different pattern of

tissue interaction. The epithelium also produced a sulcus at the upper collars of these implants. However, in most cases the sulcus did not

extend down as far as the bone surface, but ended at a 300-700µm wide band of tissue, which was attached to the base of the microtextured

collar. Even though the laser-microtexturing extended to the top of the collar, this soft tissue attachment formed only at the lower portion of

the implant collar, where a stable "corner" of soft tissue attached to both the implant collar and the bone surface. This arrangement of sulcus,

epithelial attachment, and soft tissue attachment was similar to the "biologic width" structural arrangement that has been described around

teeth and in some cases around implants.

Conclusions: This preliminary study suggests that laser microtextured surfaces can be applied to transcutaneous implants and used to improve

soft tissue integration. Results suggested that the soft tissues at the skin interface are capable of producing an arrangement similar to the

"biologic width" arrangement seen around teeth. These laser-machined microtextures are hypothesized to work by increasing surface and

organization of attached cells and tissues. They can be used to form a functionally stable interface with soft tissues, establishing an effective

transcutaneous barrier. While longer-term studies are needed, the results suggest that performance of transcutaneous prosthetic fixation may

be enhanced through the use of regional organized microtexturing.

Bone Response to Laser Microtextured Surfaces

JL Ricci, J Charvet, SR Frenkel, R Change, P Nadkarni, J Turner and H Alexander.

Bone Engineering (editor: JE Davies). Chapter 25. Published by Em2 Inc., Toronto, Canada. 2000.

RTF Cell X-Axis Growth

Figure 1. Graphs of

X-axis growth by RTF

cells on microgrooved

µm microgrooved

surfaces after 8 days

culture surface.

compared to control

Cells are attached

colonies (diameter

to tops, bottoms

grooves. Cells are

aligned along the

long axis of the

Figure 4. Scanning

RTF Cell Y-Axis Growth

electron micrograph

Figure 2. Graphs of

Y-axis growth by RTF

cells on microgrooved

µm microgrooved

surfaces after 8 days

culture surface. Cells

compared to control

are attached to tops

colonies (diameter

of grooves and span

several grooves.

Cells are aligned

along the long axis

of the substrate.

Bar=100 µm.

INTRODUCTIONTissue response to any implantable device has been found to correlate with a complex combination of material interface parameters based on composition, surface chemistry, and surface microgeometry. The relative contributions of these factors are difficult to assess.

In vitro and in vivo experiments have demonstrated the role of surface microgeometry in tissue-implant surface interaction although no well-defined relationship has been established. The general relationship, as demonstrated by in vivo experiments on metallic and ceramic implants indicates that smooth surfaces promote formation of thick fibrous tissue encapsulation and rough surfaces promote thinner soft tissue encapsulation and more intimate bone integration. Smooth and porous titanium surfaces have also been shown to have different effects on the orientation of fibrous tissue cells in vitro. Surface roughness has been shown to be a factor in tissue integration of implants with hydroxyapatite surfaces, and to alter cell attachment and growth on polymer surfaces roughened by hydrolytic etching. Roughened surfaces have also shown pronounced effects on differentiation and regulatory factor production of bone cells in vitro. Defined surface microgeometries, such as grooved and machined metals and polymer surfaces have been shown to cause cell and ECM orientation in vivo and can be used to encourage or impede epithelial downgrowth in experimental dental implants. Surface texturing has also been shown to adhere fibrin clot matrix more effectively than smooth surfaces, forming a more stable interface during the collagenous matrix contracture that occurs during healing. This is an effect which may be important in determining early events in tissue integration.

It is likely that textured surfaces work on several levels. These surfaces have higher surface areas than smooth surfaces and interdigitate with tissue in such a way as to create a more stable mechanical interface. They may also have significant effects on adhesion of fibrin clot, adhesion of more permanent extracellular matrix components, and long-term interaction of cells at stable interfaces. We have observed that, in the short term, fibrous tissue cells form an earlier and more organized collagenous capsule at smooth interfaces than at textured interfaces. We suggest that textured surfaces have an additional advantage over smooth surfaces. They inhibit colonization by fibroblastic cell types that arrive early in wound healing and encapsulate smooth substrates.

We have investigated (1) the effects of textured surfaces on colony formation by fibroblasts, and (2) the effects of controlled surface microgeometries on fibroblast colonization. Based on these results, we have designed, fabricated, and tested titanium alloy and commercially-pure titanium implants with controlled microgeometries in in vivo models. These experimental surfaces have highly-oriented, consistent microstructures which are applied using computer-controlled laser ablation techniques. The results suggest that controlled surface microgeometry, in specific size ranges, can enhance bone integration and control the local microstructural geometry of attached bone.

Cytoskeletal Organization in Three Fibroblast Variants Cultured on

Micropatterned Surfaces

JC Grew, JL Ricci.

Presented at the Sixth World Biomaterials Congress. Kamuela, HI. May 15-20, 2000.

DIRECTED TISSUE RESPONSE

Figure 1. 3T3-L1 fibroblasts cultured on 12 µm grooves. Note the

Figure 2. MC-3T3 fibroblasts cultured on a smooth surface.

uniform orientation of the elongated cells.

Introduction: Implant surface geometry and microgeometry influence tissue responses to implants. The physical and chemical properties

of synthetic substrates affect the morphology, physiology and behavior of cultured cells of various types. To date, studies of tissue-implant

interaction have emphasized cell attachment, signaling and other cellular response mechanisms. Cellular attributes influenced by micrometric

substrate features include cell shape, attachment, migration, orientation, and cytoskeletal organization. We studied three phenotypic variants

of a murine fibroblast cell line to explore the influence of substrate microgeometry on cell shape, orientation, and microfilament distribution.

Microfilament organization reflects cell shape and orientation, attendant to cell signaling events that also regulate cell attachment, mitosis,

migration and apoptosis. Microfilament bundles (stress fibers) terminate at clusters of actin-associated proteins, adhesion molecules, and

protein kinases which contribute to in vitro cell responses to culture substrates.

Methodology: NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, 3T3-Li fibroblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and MC-3T3 fibroblasts (gift of JP O'Connor) were grown in

DMEM with 10% NCS and 1% antibiotics in 24-well plates containing TiO -coated, microtextured polystyrene inserts. Culture substrates had

either 8µm parallel grooves, 12µm parallel grooves, 3x3µm square posts separated by 3µm perpendicular grooves, or no features (controls). Ten thousand cells were seeded into wells containing the inserts and after 1 day, were prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or stained with rhodamine-phalloidin.

Results: All three variants of 3T3 fibroblasts adhered to all substrates within 1 day. There was no predominant orientation or shape in

cells grown on control surfaces. The cytoplasms of some cells grown on control surfaces showed random arrays of stress fiber, apparently

terminating at focal adhesions. Nearly all cells of all types grown on 8 or 12µm grooved substrates were elongated and oriented parallel to

the grooves, growing atop the ridges or within the troughs (Figure 1). Cells cultured on 8µm grooves bridged grooves more frequently than

cells cultured on 12µm grooves. Few cells of any type demonstrated evidence of stress fibers formation after 1 day in culture on grooved

surfaces. Many cells grown on posted substrates displayed stress fibers terminating on posts. These assumed a stellate conformation, with

process extending orthogonally from a central cytoplasmic mass and terminating atop the elevated posts (Figure 1). This finding is similar to

our previous observations of NIH-3T3 cells grown on posted substrates. SEM observations confirmed the shape and orientation effects of the

substrates on the 3T3 variants.

Discussion: This experiment demonstrated that parallel and intersecting grooves dictate the cell shape, orientation and cytoskeletal organization

of three phenotypic variants of 3T3 fibroblasts. The NIH-3T3 variant is a fibrogenic line, while the 3T3-L1 variant is lipogenic and the MC-3T3

variant is osteogenic. The phenotypes of these cells were assessed by alkaline phosphatase assay (MC-3T3 cells are alkaline phosphatase

positive) and by Sudan Black B staining (for lipid inclusions in 3T3-Li cells). The roles of extracellular matrix and cell adhesion molecules in

the contact guidance events described above were not characterized, but are not discounted. We have previously demonstrated that integrin

distribution and tyrosine kinase activity is physically constrained by micrometric substrate features. We hypothesize that the same constraint

has occurred in the cells described herein. Elucidation of phenotypic differences between cell types that direct the tissue response to implants

may yield information leading to improved implant integration and extended implant lifespan.

Acknowledgements: This work was aided by NSF grants SBIR-9160684 and DUE-9750533, and by NJCU SBR grant 220253. Microgeometry molds were prepared by the Cornell Nanofabrication Facility.

DIRECTED TISSUE RESPONSE

Cytological Characteristics of 3T3 Fibroblasts Cultured on

Micropatterned Substrates

JC Grew, SR Frenkel, E Goldwyn, T Herman, and JL Ricci.

Presented at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials. April 22-26, 1998. San Diego, CA.

Introduction: Implant surface geometry and microgeometry affect tissue responses, although the tissue-implant interaction is incompletely

characterized. Physical and chemical properties of synthetic substrates affect the morphology, physiology and behavior of cultured cells of

various types. Investigators are just now beginning to describe these in vitro effects in detail. Shape, attachment, migration, orientation,

and cytoskeletal organization differ between cells cultured on flat substrates and substrates having regular surface features of micrometric

dimensions. We studied murine fibroblast shape, orientation, and microfilament and focal adhesion distribution – parameters relevant to

contact guidance and to other factors influenced by substrate microgeometry. Microfilament organization reflects cell shape and orientation,

but is also important in signal transduction schemes governing cell attachment, mitosis, migration and apoptosis. Microfilament bundles

terminate in clusters of actin-associated proteins, adhesion proteins, and protein kinases having signal transduction functions. We employed

assays that revealed the distribution of (1) microfilaments/stress fibers; (2) focal adhesion molecules; and (3) phosphotyrosine, the product of

the major class of kinases associated with cell attachments.

Methodology: 3T3 fibroblasts (ATCC, Rockville, MD) from frozen stocks were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS in multiwell plates containing

1cm square microtextured inserts. The inserts consisted of polystyrene solvent cast on silicon molds and titanium-oxide coated. The resultant

surfaces had either 8µm parallel grooves, 12µm parallel grooves, 3µm square posts (created by perpendicular 3µm grooves), or no features

(controls). Four thousand cells were seeded into wells containing the inserts and after 4 or 8 days were prepared for scanning electron

microscopy (SEM) or stained with (1) rhodamine-phalloidin; (2) either mouse antitalin or mouse antivinculin followed by rhodamine-antimouse

antibodies; or (3) fluorescein-antiphosphotyrosine antibody.

Results: By day 4, the 3T3 cells had adhered to all substrates, and by day 8 they showed considerable growth in places approaching

confluences. There was no predominant orientation or shape in cells grown on control surfaces. Their cytoplasms showed diffuse rhodamine

staining; demonstrable stress fibers were absent. Focal adhesions and phosphotyrosine were diffusely distributed. Cells grown on 8 or 12µm

grooved substrates were nearly uniformly oriented in the direction of the grooves. Cells cultured on 8µm grooves mostly grew atop the ridges,

often bridging the troughs between ridges. Cells cultured on 12µm grooves mostly grew either atop the ridges or within the troughs, only

infrequently bridging the troughs between ridges. Some cells demonstrated limited evidence of stress fibers after 8 days in culture on the

grooved surfaces. Focal adhesions and phosphotyrosine were limited to areas of cell-substrate contact; portions of cells spanning troughs