Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Microsoft word - neopterinenglish.doc

Fig. 1: Neopterin (D-erythro-1', 2', 3'-trihydroxypropylpterin)

Determinations of neopterin levels reflect the stage of activation of the cellular immune system which is of

importance in the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases, e.g., in viral infections, in autoimmune

or inflammatory diseases, rejection episodes following allograft transplantation and in several malignant

diseases. Besides the importance of neopterin as a diagnostic marker new aspects point to a possible

biological role of neopterin derivatives

(hard copies of this monograph are available at www.brahms.de).

1. Introduction Increased neopterin concentrations in body-fluids, such as serum or urine, are connected with diseases

linked with cellular immune reaction [1-6], e.g. viral infections, including HIV infection and infections by

intracellularly living bacteria or parasites, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases, rejection episodes

following organ transplantation and certain malignant diseases. In all these different diseases the cellular

immune system is involved in the pathogenesis and/or affected by the underlying disease process, and

neopterin concentrations are very closely linked with the progression of these diseases. Therefore it is of

interest for laboratory diagnosis to measure the degree of activation of the human immune system. This is

possible in an easy but specific way by the determination of neopterin concentrations.

2. Relationship between immune activation, release of cytokines and formation of

neopterin 2.1. Immunological and biological background of neopterin formation

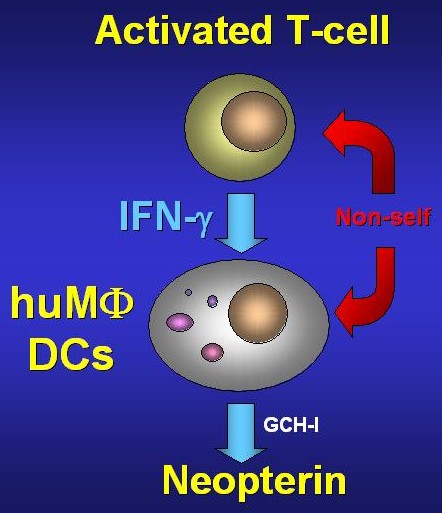

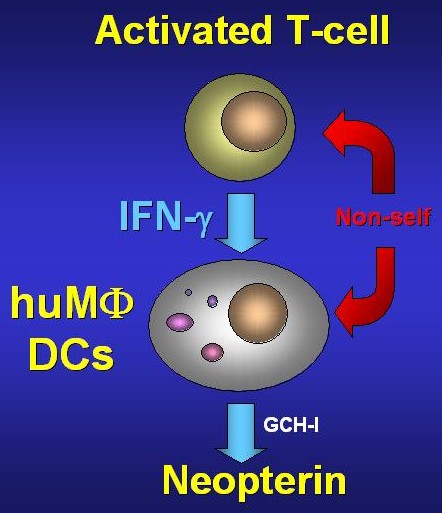

If T-lymphocytes recognize foreign or modified-self cell structures they start producing different mediators,

so-called lymphokines, such as interferon-γ. In a next step the formed interferon stimulates human

monocytes/macrophages for the production and release of neopterin (Fig.2) [7]. Neopterin, 6-D-erythro-

trihydroxypropyl-pterin, is a substance of low molecular mass, that becomes biosynthesized from guanosine-

triphosphate (GTP) by the key-enzyme of pteridine-biosynthesis: GTP-cyclohydrolase I.

Thereby, GTP-cyclohydrolase cleaves guanosine triphosphate to form 7,8-dihydroneopterin-triphosphate as

an intermediate. Unlike other cells and species human monocytes/ macrophages only have a small

constitutive activity of the biopterin-forming enzyme pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS), so that

almost exclusively neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin become synthesized and released [8]. Because of this

considerable amounts of neopterin are only found in body-fluids of humans and primates. Accordingly, in

supernatants of cultured human cells other than monocytes/macrophages or cells of other species almost

exclusively biopterin derivates are detected and only in cell cultures of human monocytes/macrophages or of

the myelomonocytic cell line THP-1 relevant amounts of neopterin are released. Interferon-γ was identified as

the only cytokine that induces significant production of neopterin [9]. Other cytokines like different

interleukins as well as factors inducing phagocytosis, e.g. zymosane, are unable to operate in this way. Also

tumor necrosis factor-α cannot induce the formation of neopterin directly, it however costimulates the release

of neopterin triggered by interferon-γ [10, 11]. There is reason to believe that the extent of neopterin

formation reflects the combined effect of positively- and negatively-regulating influences on the population of

monocytes/macrophages activated by interferon-γ. Interferon-γ is mainly formed by activated T-lymphocytes

Figure 2: During cellular immune response,

activated T-lymphocytes of the TH1-subtype

release interferon-γ which in human

macrophages (MΦ) and dendritic cells (DC)

stimulates the enzyme GTP-cylohydrolase (GCH)

and thus neopterin production.

and it is the definite trigger for neopterin formation. That is why the degree of activation of the T-lymphocytes, especially of so-called TH-1-type cells, which are responsible for the production of interferon-γ and interleukin-2 [Fig. 2], is of great importance for neopterin production [12]. Therefore substances that may influence the activity of this T-cell population are able to modify the degree of the activation of monocytes/macrophages indirectly and as a consequence the formation of neopterin. Exogenous addition of interleukin-2 to peripheral mononuclear cells but also in vivo leads to an increase of neopterin expression by the way of activation and expansion of T-cells, although there is no direct influence of this cytokine on neopterin production by monocytes/macrophages. Similarly, interleukin-12 is also able to amplify neopterin formation. On the opposit, immunsupressants such as cyclosporin-A, which inhibits formation of cytokines by Tcells, also reduce neopterin production.

Figure 3: Formation of neopterin

from guanosine triphosphate (GTP):

cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH-1) cleaves

GTP to form 7,8-dihydroneopterin-

triphosphate. Because of a relative

deficiency of the 6-pyruvoyl-

tetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS) in

human monocytes/macrophages

neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin

are formed after dephosphorylation

and oxidation at the expense of

biopterin derivatives.

The value of neopterin monitoring is superior compared to the direct analysis of interferon-γ. Neopterin is biochemically inert and its half-life in the human organism is only due to renal excretion. The biological half-life and as a consequence the diagnostic accessibility of cytokines are limited by several circumstances: for instance released interferon-γ is bound very quickly to target structures or becomes neutralized by soluble

receptors. Because of this, locally formed cytokines often are unable to reach the blood circulation and are

no good targets for routine laboratory diagnosis [13]. Beyond that, measurement of neopterin levels does not

solely reflect the effect of one single cytokine, rather it allows to determine the total effect of the

immunological network and interactions on the population of monocytes/ macrophages. The reflection of the

multiple cooperations between immunocompetent cells seems to be the basis for the remarkable value of

neopterin analyses as an immunodiagnostic tool.

Beside the processes that are connected with an activated cellular immune system, increased neopterin

levels can be found in a rare inborn metabolic defect of biopterin biosynthesis, namely atypical

phenylketonuria (PKU), in which detection of neopterin is also used for differential diagnosis [14]. Atypical

PKU is linked with increased blood levels of phenylalanine in blood as it is the case in classical PKU and it is

diagnosed in the first months of life. The incidence of this inborn defect which leads to an increase of

neopterin in body-fluids is lower than 1 out of 1 million newborns.

2.2. Neopterin derivates and redox systems

Recent data indicate a possible participation of neopterin derivates within cytotoxic mechanism of

macrophages [15]. On the one hand, a strong correlation between detection of neopterin and ability of

monocytes/ macrophages to set free reactive oxygen species [16] was found. Thus, neopterin determination

can be considered as an indirect marker for the amount of immunologically induced oxidative stress. On the

other hand, neopterin derivates are able to influence the effects of reactive oxygen, nitrogen and clorine

species. Investigating luminol chemiluminescence it was demonstrated that neopterin is a potent enhancer of

various reactive substances, such as H2O2, HOCl, chloramine and peroxynitrite (ONOO-, an effector

molecule of nitric oxide radical, NO), while 7,8-dihydroneopterin is mainly acting as a scavanger. These

results suggest a new physiological role of the neopterin formation, namely as an endogenous regulator of

cytotoxic effector functions of activated macrophages [15].

Since neopterin production is a specific peculiarity for macrophages of primates it is of interest to clarify for

what purpose these cells have obtained this additional ability. One of the most important cytotoxic reactions

of macrophages stimulated by interferon-γ is the production of NO from arginine by the so-called inducible

NO synthase (iNOS). This mechanism is known for various species, but until now it was detectable in

humans only very limited [19]. iNOS requires 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin as a cofactor for its function which is

available only in a very low concentration in activated human monocytes/macrophages because of the

excess production of neopterin. Therefore, it seems reasonable that this in the human monocytes/

macrophages deficient cytotoxic mechanism should be compensated by enhanced production of neopterin

[20]. Besides it was found that neopterin is also able to enhance the effects of ONOO- [18, 21].

Neopterin derivates seem to be able to interfere also with molecular biological pathways that are regulated

by redox-balances in general. In vitro, derivatives of neopterin induce expression of the nuclear factor-κB

[22,23] and of the iNOS-gene [24]. Similar to this, programmed cell death, apoptosis, is induced or intensified

by neopterin derivates [25,26] and for example formation of erythropoetin is inhibited [27]. Recent reports

show that neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin upregulate expression of proto-oncogene c-fos [28], so these

substances may be even involved in malignant transformation of cells.

3. Neopterin detection in body fluids

Neopterin is a low molecular weight substance which is biologically and chemically stable in body fluids, and

it can be applied without difficulty for routine measurements in laboratory diagnosis. Neopterin is eliminated

by the kidney, and changes of neopterin concentrations in serum are reflected by urine levels [30] as long as

renal function is not impaired. In fact, there is an equal sensitivity of neopterin measurements either in serum

or urine. Measurement of 7,8-dihydroneopterin is not suitable for routine application in laboratory diagnosis

[29]. This derivative is chemically unstable and easily decomposes due to oxidation, so that more stringent

criteria for sample collection and handling restrict its usefulness as a clinical diagnostic. Because also

neopterin is slightly sensitive to direct sun light irradiation, samples must be protected from light during

transport and storage. In general enveloping of the samples, e.g. in aluminum foil, is sufficient, alternatively

dark tubes may be used for collecting samples.

3.1. Detection in protein containing body fluids

Favourably neopterin levels in serum, plasma and other protein-containing body fluids, e.g. cerebrospinal

fluid, pancreatic juice or ascites are determined by immunoassays (ELISA or radioimmunoassay) [29,30-32].

Neopterin concentrations in serum or plasma do not differ. For a single measurement of neopterin by

immunoassay 20-100µl of serum, plasma or cerebrospinal fluid are required.

The content of neopterin in serum or plasma is stable for 3 days at room temperature, this allows mailing of

samples without special cooling. For storage until one week cooling at 4°C is adequate, for a longer period of

time the samples must be kept frozen (-20°C till three months). Repeated thawing-freezing cycles must be

avoided, it may decrease the content of neopterin. For measurements of neopterin concentrations in bile

fluid [33] it is useful to dilute the samples with physiologic NaCl solution (=0.9% acqueous NaCl), e.g. 100µl

bile fluid plus 1000µl NaCl solution.

3.2. Neopterin measurements in urine

Usually for the determination of neopterin in urine samples high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) on

reversed phase (e.g., C18) with Sörensen phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.015 M, pH = 6.4) as eluent (flow rate =

1.0 ml/min) is applied. It allows a rapid, sensitive and precise detection and meets the requirements of

quality in clinical chemical investigations [29]. 100 µl urine are mixed with 1000 µl elution buffer containing

2g/l EDTA to dissolve eventual urinary sediments. Neopterin is detected by measurement of its natural

fluorescence (excitation wavelength 353 nm, emission wavelength 438 nm). After each day (= up to 100

samples), cleaning of the column is performed with a 20 min. gradient from buffer via water to 100%

methanol, remaining on methanol for 20 min., then gradient via water goes back to buffer (within 20 min.).

Immunological methods are identical to the HPLC measurement. However, it has to be considered that

neopterin concentrations in urine specimens spread within a greater range, because physiological dilution of

urine adds to immunological changes of concentrations. Thus, it may become necessary to repeat

measurements of the urine samples with concentrations beyond the range of linearity after an additional

dilution step.

It is appropriate to use the first morning urine instead of the 24 hours urine to avoid laborious collection of 24

hours urine. Physiological differences in urine densities are taken into account by calculating the ratio of

neopterin concentrations versus urinary creatinine which can be used as an internal standard since

creatinine is excreted in relatively constant amounts during the day. When using HPLC for neopterin

measurements, creatinine concentrations can be measured in parallel in the same chromatographic run by

detection of its UV-absorption at 235 nm wavelength. The quotients neopterin/creatinine are usually

expressed in µmol neopterin/mol creatinine. There exists a diurnal variation of the neopterin/creatinine ratios:

in first morning urine specimens higher ratios (about +20%) are found than during the day (Table 1).

For a single detection by HPLC 100 µl of urine are necessary. Neopterin concentrations in urine specimens

are stable for at least 3 days at room temperature, for storage till one week cooling at 4°C is sufficient, for a

longer period of time samples must be kept frozen. Repeated thawing-freezing cycles have to be avoided.

3.3. Normal values

There is no difference between neopterin values detected in serum or plasma. On average the

concentrations are 5.2+2.5 nmol/l neopterin (Table 1). Normal values and upper limits of tolerance (95th

percentiles) depend on age. Therefore it is necessary to classify neopterin concentrations according to three

age groups (Table 1). Neopterin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid are somewhat lower than those in

serum or plasma [34].

Tabelle 1: Neopterin concentrations (mean + S.D. and 97.5th percentiles) in various

body fluids of healthy individuals

Neopterin in urine (µmol/mol creatinine):

Neopterin in serum (nmol/l):

Males and females

Neopterin in cerebrospinal fluid (nmol/l):

Males and females

Neopterin concentrations detected in the first morning urine are about 1500 nmol/l, concentrations of

creatinine about 12 mmol/l; thus the normal value of healthy persons is calculated as about 125+5 µmol

neopterin/mol creatinine. Normal values and upper limits of tolerance of urinary neopterin concentrations in

healthy persons slightly depend on age and sex, which is mainly due to variations of urinary creatinine

concentrations (Table 1).

Renal clearence of neopterin is similar to that of creatinine. Therefore neopterin per creatinine ratios in urine

are not influenced by renal impairment [30]. Unlike to that blood neopterin concentrations depend on renal

function, reduced renal excretion causes accumulation of neopterin in blood and one may find extremly high

values in serum or plasma (200 nmol/l and more) in patients wirth uremia [35]. Thus, in patients with

impaired renal function accumulation of neopterin may occur in the blood which is in addition to the

enhanced formation of neopterin by immune system activation. Calculating the neopterin per creatinine ratio

is suitable to at least partly account for the accumulation due to renal retardation.

4. Clinical application of neopterin measurements

In Table 2 useful applications of neopterin measurements in clinical laboratory diagnosis are listed. The

following chapters provide a more detailed description of the value of neopterin measurements in these

clinical situations.

Table 2.: List of applications for neopterin measurements in clinical diagnosis

Infections

virus infections and infections with intracellularly living bacteria and

special importance for predicting prognosis in HIV infected persons

help for differential diagnosis between infections with bacteria versus

viruses

Autoimmune diseases and other inflammatory diseases

rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener's

granulomatosis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis

help for differential diagnosis, e.g., rheumatoid arthritis versus

osteoarthritis

Malignant diseases

predicting prognosis and follow-up in gynecological and hematological

neoplasias, bronchus carcinoma and cancer of the prostate,

gastrointestinal

Allograft transplantation

Recognition of immunological complications like rejection or infection

Monitoring of treatment

immunmodulating therapy with cytokines

in diseases leading to increased neopterin levels (e.g., antiretroviral

therapy of HIV-infection, antibacterial therapy of tuberculosis)

4.1. Infections

When the organism is challenged by infections with viruses, intracellularly living bacteria, parasites or fungi

the cellular immune system becomes activated. In addition, immunological processes can be initiated by

endotoxins produced by gram-negative bacteria which leads to an activation of T-lymphocytes and formation

of interferon-γ and thus may lead to an increase of neopterin concentrations in body fluids.

4.1.1. Viral infections

In almost all patients with acute viral infections neopterin levels are increased, this was demonstrated in

patients with acute hepatitis A or B [36], patients with Epstein-Barr-virus infection (infectious mononucleosis)

and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection [37] but also in patients with measles. Usually neopterin concenrations

closely reflect the extent and the activity of the disease. Neopterin determinations may also be used as an

additional parameter for differential diagnosis, e.g. patients with chronic non A/non B-hepatitis show significantly higher neopterin levels than patients with non-infectious fatty liver [39]. During the course of viral infections neopterin levels usually increase already before first symptoms appear and before formation of specific antibodies becomes detectable [1]. After antibody seroconversion neopterin levels decrease and return into the normal range during the period of reconvalescence within a few days (Fig.5). The course of neopterin concentrations does not differ essentially between various viral infections, e.g. neopterin concentrations behave similar during infections with CMV, a DNA-viruses, and rubella, which is caused by an RNA-virus [40,41].

Figure 4: Schematic course of neopterin levels in a patient during an acute rubella virus infection

(left, [41]) and during an acute HIV-infection (right, [42]): In both events the increase of neopterin

levels begins before seroconversion (IgG+). In contrast to the rubella virus infection in which the

neopterin levels return to baseline after seroconversion, they usually remain elevated following acute

HIV-infection (right).

4.1.1.1. Infections with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Increased neopterin levels in serum and urine can be found in almost 100% of patients with AIDS. But

already in early stages of HIV-infection increased neopterin levels are frequently found [1]. The range of

neopterin levels in the acute stage of the HIV infection is similar to that of other virus infections especially in

the period before seroconversion, but unlike to other infections after seroconversion neopterin levels do not

normalize completely in HIV infected individuals [42]. In contrast, after seroconversion neopterin levels

remain outside the normal range [43,44] in about 80% of HIV infected individuals. Thus, the subsequent

asymptomatic stage of HIV infection is associated with chronically increased neopterin levels in almost every

individual. With the progression of the disease neopterin levels increase more and more, and highest values

of neopterin in serum and urine are detected in patients with AIDS (Fig.5).

This development of neopterin concentrations was confirmed in rhesus macaques experimentally infected

with simian immundeficiency virus, SIV, a simian analog of HIV [45]. In this case neopterin levels also

increase after inoculation of SIV within about 5 days, again before seroconversion takes place. Afterwards

neopterin levels decline but remain outside the normal range, then correlating with the progression of the

infection.

Neopterin has become a well accepted parameter for the prediction of the future course of the HIV infection

[43,44,46]. More rapid disease progrssion is early indicated by higher and further increasing neopterin levels.

Already at an early stage neopterin values provide a significant prognostic information for the future course

of the infection and for the risk of developing AIDS or for death (Fig.6). The predictive value of neopterin

concentrations is at least comparable to that of the number of CD4+ T-cells [43]. More recent studies show

that neopterin monitoring is also useful in addition to quantitative measurements of virus load such as

Figure 5: Schematic course of

neopterin levels (yellow bars) in

HIV infected persons: After the

acute infection in approximately

three-fourth of the HIV antibody

seropositive individuals the

neopterin levels remain

increased also during the

asymptomatic period of the

infection; when progression of

the disease takes place (AIDS

related-complex = ARC, AIDS)

neopterin levels further

increase. The number of CD4+

T-cells (red) correlates usually

inversely to the neopterin levels,

a direct correlation exists

between neopterin

concentrations and quantitative

measurements of virus

load (blue) such as HIV mRNA

measured by polymerase chain

reaction.

dissociated HIV antigen and HIV-RNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction [47].

Figure 6: Prognostic value of

neopterin levels in HIV-infected

persons: within the

observation period of

72months individuals with

higher neopterin levels at

study entry (>307 µmol

neopterin/mol creatinine in

urine) developed AIDS more

rapidly than individuals with

higher neopterin levels (keft)

[43]. In the same patients,

lower CD4+ cell counts

(<480/mm³) indicated more

rapid disease progression

(right).

Successful treatment of HIV infection by antiretroviral therapy is associated with a decline of neopterin levels [48] within a few days. E.g., after one week HIV infected persons treated with zidovudine (azidothymidine) reached a plateau corresponding on average to 50% from the baseline value measured before treatment (Fig.7). Interestingly differences between the various reverse transcriptase inhibitors to influence neopterin levels could be found [49]. Increased neopterin levels in patients with HIV infection point to an increased activity of the cellular immune system which is caused by the reproduction of the virus in the organism. A connection was found between neopterin levels and distinct properties of the virus: HIV can be isolated much easier from patients with higher neopterin levels, and the virus isolates from individuals with higher neopterin levels tend to an accelerated replication rate with higher reverse transcriptase activity [50]. All together neopterin values emphazise the importance of immunological activation processes and cytokine cascades for the progression of HIV infection. Associations between neopterin levels in patients and the development of anemia [51] and cachexia [52] show the significance of immune activation for the clinical course of HIV infection. Moreover, neopterin derivatives themselves seem to have potency to accelerate the replication rate of HIV via an enhancment of oxidative stress [53,54].

Figure 7: Schematic course

of neopterin levels in HIV

infected individuals during

therapy with zidovudine

(azidothymidine): in case of

successful therapy

neopterin levels decrease

within a few days [49].

In patients with HIV infection a tight connection between neopterin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) and the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms was found. HIV-associated dementia is

associated with strong intrathecal formation of neopterin, in this case neopterin levels in CSF reach

significantly higher values than in serum [55,56]. By measurements of neopterin levels in CSF it is possible

to monitor the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy to penetrate through the blood-brain barrier [49].

4.1.2. Infections with parasites and intracellular bacteria

Increased neopterin levels are detected in infections with intracellularly living bacteria and parasites such as

tuberculosis [57,58], leprosy [59], melioidosis [60], malaria [61,62] and schistosomiasis [63]. In nearly every

patient with acute malaria increased neopterin levels are found, moreover even asymptomatic children with

low-grade parasitaemia present with increased neopterin levels. Besides, a temporal connection between

the development of malaria symptoms and neopterin levels in serum was demonstrated by experimental

infection of healthy volunteers with Plasmodium falciparum [64]. In that study it was shown that the increase

of neopterin levels may even precede fever reactions.

In patients with pulmonary tuberculosis neopterin levels [57] correspond to the extent and the activity of the

disease. During therapy neopterin values show a prompter response than usually applied methods such as

blood sedimentation rate or X-ray. Worsening of the disease is indicated early by rising neopterin

concentrations.

4.1.3. Differential diagnosis between viral and bacterial infections

Figure 8: Neopterin levels (upper) and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR, lower) in patients with viral and

bacterial pneumonias. In contrast to lower ESR,

neopterin levels are significantly higher in patients with

viral infections than in bacterial infections [65].

Neopterin measurements are able to support differential diagnosis between viral and bacterial infections [65].

In contrast to highly increased neopterin levels in patients with virus infections, in patients with acute

bacterial infections usually normal or only slightly increased values can be detected (Fig.8). It could be

shown that neopterin measurements are even better able to distinguish between acute viral or bacterial

infection than blood sedimentation rate or leucocyte counts [65], although in this study both the latter

methods were used for differential diagnosis of infections. It is important to note that protracted bacterial

infections often are associated with increased neopterin levels.

4.1.4. Multiple trauma and sepsis

In traumatized or post-operative patients in intensive care medicine serum neopterin levels were shown to

predict the development of septic complications. In patients with multiple trauma significantly higher levels

are found in patients who later develop sepsis [66] than in aseptic patients. In septic patients neopterin

concentrations predict survival, non-survivers presenting with higher neopterin levels than survivors. Similar

results were shown in patients with acute pancreatitis [67]. Already at the time of admission at the hospital

neopterin concentrations allowed a significant prediction of patients' survival. The predictive value of serum

neopterin levels was superior to that of, e.g., C-reactive protein.

4.1.5. Cerebral infections

Neopterin penetrates through the blood-brain-barrier, so that there usually exists a linear relationship

between neopterin levels in blood and in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [55]. In contrast during the course of

cerebral infections also intrathecal neopterin formation occurs, and in this case neopterin levels in CSF

reflect the activity of intrathecal disease very closely [34]. In patients with acute Lyme neuroborreliosis

extremly high neopterin levels in CSF (>100 nmol/l) were detected [68], which closely reflected disease

activity and subsequently also the impact of, e.g., antibacterial treatment on the infectious process was

indicated. In serum of these patients one usually can find only minor changes which take place within the

normal range. Analogously high neopterin levels in CSF are common in encephalitis of viral and bacterial

origin [34]. Because neopterin levels in serum are normal in absence of a systemic infection, neopterin

determinations in CSF and serum are helpful for the differential diagnosis of, e.g., febrile convulsions and

meningitis in children [69,70].

4.2. Autoimmune diseases and other inflammatory diseases

Neopterin levels in autoimmune diseases correlate with the fluctuating course and reflect the severity of the

disease in a sensitive and convenient way.

4.2.1. Rheumatoid arthritis

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis neopterin levels correspond with the extent of the disease [71]. Average

values of neopterin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis even in stage 1 are already higher than in patients

with osteoarthritis, so neopterin detection also may support differential diagnosis in these cases. With the

Figure 9: Neopterin levels in

patients suffering from

rheumatoid arthritis: patients

with rheumatoid arthritis

show increased levels in

comparison to controls (CO)

and patients with

osteoarthritis (OA). In

patients with rheumatoid

arthritis a close association

between higher neopterin

levels and the activity of the

disease was demonstrated

(activity scores I - IV) [71].

progression of the disease higher neopterin levels are found. The influence of the clinical activity of the

disease on neopterin levels is even stronger than that of the stage of the disease (Fig.9). Neopterin levels in

follow-up show changes of the activity very sensitively which is especially important to indicate periods in

which therapy has to be applied. It is to point out that neopterin concentrations in synovial fluid of patients

suffering from rheumatoid arthritis are higher than in serum, and the concentrations of neopterin in synovial

fluid reflect the activity of disease even better than serum or urine concentrations do [72].

4.2.3. Systemic lupus erythematosus

In acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) neopterin levels are highly increased and correspond tightly

with the activity of the disease (Fig.10) [73,74]. In a mutlivariate analysis of several standard laboratory

parameters and different markers of immunological activity, e.g. soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor,

soluble interleukin-2 receptor and soluble CD8 neopterin in a combination with blood sedimentation rate was

found to be the best indicator for the activity of SLE [68].

Figure 10: Neopterin levels

compared to the clinical activity

(European Consens Lupus

Activity

patients suffering from systemic

lupus erythematosus [73].

4.2.4. Wegener's granulomatosis, dermatomyositis

About two thirds of patients with Wegener's granulomatosis show increased neopterin levels in serum.

Neopterin values correlate significantly with the activity of the disease as expressed by the Birmingham

vasculitis activity score [75]. Similar results are found in patints suffering from dermatomyositis [76], where

again a correlation with the activity of the disease was demonstrated. Particularly in patients with

polymyositis extremly high neopterin levels are detectable.

4.2.5. Inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract

As in rheumatoid arthritis and SLE also in inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract like Crohn's

disease [77], ulcerative colitis [78] or celiac disease [79] neopterin levels are tightly connected with the

clinical activity, e.g., in patients suffering from Crohn's disease with the help of neopterin values an activity

score was developed, which is based on only two further parameters, namely haematocrit and frequency of

liquid stools. This simple activity index achieves similar significant results as the well established Crohn's

Disease Activity Index (CDAI) [77]. Moreover quantification of neopterin in inflammatory diseases of the

gastrointestinal tract is helpful to monitor treatment. In children suffering from celiac disease a rapid decline

of neopterin concentrations is seen during gluten-free diet [79].

4.2.6. Lung sarcoidosis

In the majority of patients with active sarcoidosis neopterin levels are increased correlating to disease

activity. Neopterin concentrations in serum and urine and also in the bronchoalveolar lage fluid rise in a

direct relationship to the roentgenologic stages [80]. In the follow up of patients clinical improvement is

indicated by decreasing, worsening by increasing neopterin levels.

4.2.7. Multiple sclerosis

Neopterin levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with multiple sclerosis are significantly higher in the

acute phase of disease than in stable periods [81]. Moreover detection in CSF may also support differential

diagnosis, e.g., it is important to note that patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have normal neopterin

levels in serum and CSF [82].

4.2.8. Cardiovascular diseases

Patients with dilated cardiomyopathy show increased neopterin levels, the values corresponding with the

stage of the disease [83]. Furthermore correlations with the extent of cardiac impairment were found. In

children with Kawasaki disease also increased neopterin levels are detected [84], during follow up neopterin

concentrations reflect the efficacy of, e.g. therapy with immunoglobulins. Also patients with acute rheumatic

fever show increased neopterin levels with high frequency [85]. In this case higher neopterin levels indicate

an increased risk for the development of valve lesions. Healthy individuals with an increased risk for

arteriosclerosis present with statistically higher neopterin levels than persons with lower risk, but the analized

changes of the neopterin levels usually remain within the normal ranges for healthy individuals [86]. In

contrast in patients after myocardial infarction temporarily increased neopterin levels were reported [87].

4.3. Malignant diseases

Certain malignant diseases are associated with elevated neopterin concentrations. However, since neopterin

is released by cells of the immune system but not by tumor cells neopterin is not a tumor marker in the

common sense: T-cell activation, probably induced by malignant cells, leads to formation of cytokines and to

activation of monocytes/macrophages for neopterin production. The sensitivity of neopterin changes

depends very much on the location and the type of the malignant process [88]. Most patients with

hematological neoplasias show increased neopterin levels whereas in patients suffering from breast cancer

hardly increased levels can be found. But in general neopterin concentrations in body fluids of patients with

malignant diseases correlate with the extent of the disease, respectively the tumor mass, and indicate a

higher risk for progression of the disease. Consequently the utility of neopterin measurments in malignant

diseases does not lie in the so-called tumor screening but in judging prognosis and in the monitoring of

therapy [89-91]. A significant predictive value for prognosis of the neopterin levels before therapy was found,

e.g., in patients with gynecological and hematological neoplasias, in patients with bronchus carcinoma,

cancer of the prostate, hepatocellular carcinoma and with gastrointestinal cancer. During follow-up of

Figure 11: In patients

with malignant

tumors(example

shown: carcinoma of

the prostate) neopterin

levels (mean + S.D.)

increase with higher

stage (stages A – D).

Higher neopterin

concentrations are

associated with

shortened survival).

patients a tight connection between an uncomplicated course of the disease and normal neopterin levels

was demonstrable. In contrast, incomplete removal of the tumor or recurrence of the malignant event

correlates with remainingly high or increasing neopterin levels [90]. Therefore, the measurement of neopterin

represents a possibility for additional monitoring especially during the follow-up of patients. In this case

increasing neopterin levels indicate the need of further diagnostical measures because neopterin changes

are due to immune deterioration which not necessarily must be a result of the tumor disease. Besides

neopterin detection may be used also for diagnosis as an additional indicator to differentiate between

benigne or malignant tumor diseases.

Increased neopterin levels in different tumor diseases reflect the importance of immune activation for the

clinical course of the disease. As in HIV infected persons associations between neopterin levels and the

presence of anemia or cachexia in these patients can be found [93,94], which points to the role of inhibitory

cytokines in the pathogenesis of these symptoms. The same cytokines that are mainly responsible for

neopterin formation seem to have an essential importance for the development of anemia and weight loss

[95]. Recent results demonstrate that neopterin metabolism may even be involved directly in the malignant

event, namely by interfering with intracellular signal-transduction pathways which are sensitive to oxidative

stress, because neopterin and dihydroneopterin are able to interfere with redox equilibria in cells and were

shown to promote the expression of protooncogene c-fos [28].

4.4. Monitoring of graft recipients

In recipients of solid allografts (kidney, liver, pancreas and heart) daily neopterin monitoring during the

hospital stay represents a sensitive way to detect immunological complications like rejection or infections

early [96]. On average already two days, sometimes even 7 days, before clinical complications may occur

neopterin levels begin to increase significantly (Fig.12). But increased neopterin values can only be

interpreted as a warning signal for developing immunological complications and have to become further

clarified by additional differential diagnostic measures. In follow-up it was also shown that neopterin levels

during the post-operative phase are associated with the long-term graft survival [97], higher neopterin levels

are associated with a significantly shorter graft survival.

Figure 12: Schematic course of

neopterin levels in a patient after

kidney-transplantation (blue) as

compared with an uncomplicated

course (purple). Rejection episodes

are indicated by increasing

neopterin levels on average

approximately 2 days before

clincial diagnosis is established by

convential means [96]; successful

immunosuppressive therapy of the

rejection leads to a decrease of

neopterin levels.

If neopterin detection in serum or plasma is utilized for the follow-up of patients after kidney transplantation it is necessary to calculate a quotient of neopterin versus creatinine concentrations (similar to the proceedure for neopterin measurements in spot urine specimens). By this way changes of neopterin concentrations due to renal impairment but not caused by an underlying immune response can be at least partly taken into account (see also chapter 3.3.). Monitoring of neopterin concentrations in other body fluids such as bile fluid or pancreatic juice of patients after allograft transplantations provides further support for differential diagnosis, e.g., neopterin measurements in pancreatic juice [98] after combined kidney/pancreas transplantation allows to identify the

organ which is experiencing immunologal complications. In a similar way contemporary monitoring of

neopterin concentrations in bile fluid and serum in liver graft recipients further helps to find out whether a

patient is concerned either with rejection or systemic versus hepatic infections [32].

During the course before and after bone marrow transplantation the aplastic phase caused by chemotherapy

and/or whole body irradiation before transplantation is associated with low or even decreased neopterin

levels [99]. Hematological reconstitution is associated with increasing neopterin levels and the so-called

"hematological take" is indicated approximately 7 days in advance. During and before viral infections or graft-

versus-host (GvH) disease neopterin values usually rise dramaticaly. Thus, neopterin measurements are

useful for the follow-up after bone marrow transplanation to distinguish between uncomplicated and

complicated courses with viral infections or GvH reactions.

4.5. Immunomodulating therapy and follow-up of therapy

Because of its formation during the course of cell-mediated immune response neopterin monitoring allows to

determine the effects of therapeutical interventions which are assigned to interfere with the degree of

immune activation. Particularly in therapies with cytokines such as interferons, interleukins or tumor necrosis

factor-α a dose-dependent increase of neopterin occurs, so that monitoring of neopterin concentrations

allows to define an optimal dosage of immune-modulating therapy [100]. Beside measurement of neopterin

concentrations is also performed for monitoring patients with malignant diseases during treatment with

immunotherapy applying antitumoral peptides.

Except the monitoring of therapeutical measures that operate directly on the immunologic network neopterin

determinations allow to examine therapeutic effects during clinical situations in which neopterin

concentrations reflect the activity of the disease. Usually successful surgical intervention to remove a

malignant tumor leads to a decrease of neopterin concentrations [89]. Similarly successful antibacterial

treatment of, e.g. pulmonary tuberculosis, is associated with rapidly decreasing neopterin levels [57,58].

Therefore efficacy of treatment or even the compliance of patients can be monitored by neopterin

measurements. Similar results were found in patients with acute rheumatic fever [85], Lyme neuroborreliosis

[68] or autoimmune diseases.

4.6. Blood transfusion and bone banking

Transfusion of blood or blood-products bears a certain risk for transmitting infectious agents or probably also

malignant processes. Untill now only very few specific tests for antibodies against the most dangerous

agents, namely HIV and hepatitis viruses, are performed on a regular basis. Because of logistic reasons it is

only possible to introduce a limited number of such specific tests for the routine screening of blood

donations. Since there are various different pathogens which cannot be screened for by this strategy,

anamnestic examinations of donors should at least partly fill this gap. Therefore, a so-called "nonspecific

test" like measurements of neopterin concentrations would be useful to detect various disorders which

represent a certain risk for blood transfusion recipients. Infections with viruses including retroviruses,

intracellularly living bacteria but also autoimmune processes and certain malignant diseases lead to an

activation of the cellular immune system and consequently to increased neopterin concentrations in

individuals even when they still may feel free of any symptom. The sensitivity of neopterin measurements is

high to detect such disorders, and a reasonable number of investigations demonstrates that the

measurement of neopterin is well practicable as a screening test in the field of blood transfusion [101].

Thereby it has to be pointed out that neopterin levels are already increased in an early stage of an infection,

even before specific antibodies are formed (compare chapter 4.1.) to be able to further close the so-called

"window period" which still exists when antibody screening is performed.

In Austria measurements of neopterin concentrations became obligatory for all blood-donations in 1994, in

the Austrian province of the Tyrol screening of blood donations by neopterin measurements has already

been performed since 1986 according to an order of the local government. In the meantime it was found that

an additional screening with neopterin measurements of blood donation is able to reduce the risk of

transmitting acute virus infections, e.g., neopterin screening was shown to reduce the risk of missing acute

CMV infections in blood donations by a factor of 17; in donations with increased neopterin levels (>10 nmol/l)

approximately a 17-fold higher frequency of acute CMV infections was found compared to donors with low

neopterin levels [102]. Importantly in that study anamnestic examination was done as usual before the

donation was allowed, but the acute infections were not recognized by anamnesis or by the donor himself.

Moreover it was demonstrated that in an asymptomatic course of CMV infection the increase of neopterin

even starts before CMV-IgM seroconversion, and CMV-IgM seropositivity correlated with the highest

neopterin values (Fig.12). Similarly donors with increased neopterin levels the occurence of an acute

Epstein-Barr-virus infection or parvovirus infection was 4 to 6 times more likely than in the donors with

neopterin levels within the normal range [103].

Besides neopterin measurement are also nominated as an additional method for the screening of bone donors [104]. Particularly the diagnosis of malignant diseases and infections in donors becomes supported by additional neopterin measurements.

Figure 13: Neopterin levels in blood

donors during asymptomatic acute

CMV infection: in approximately 5% of

blood-donors with neopterin levels

above 10nmol/l acute CMV-infections

can be confirmed by CMV-IgM

seropositivity (CMV-IgM+, A) [102];

after complete seroconversion the

neopterin levels of most of these

donors decrease to the normal range

(IgG+, B). Among donors with

increased neopterin levels individuals

were found who were still completely

seronegative for CMV (CMV/IgM and

IgG-, A), but in a subsequent donation

became CMV/IgM+ and afterwards

also developed CMV-IgG antibodies

(C). Thus, CMV infection was

detecable by increased neopterin

concentrations not only before IgG-

seroconversion but also before

detectable IgM.

5. References

1. Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Neopterin as a marker for

activated cell-mediated immunity: Application in HIV infection. Immunol Today 1988:9;150-5.

2. Wachter H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER. Neopterin as marker for activation of cellular

immunity: Immunologic basis and clinical application. Adv Clin Chem 1989:27;81-141.

3. Fuchs D, Weiss G, Reibnegger G, Wachter H. The role of neopterin as a monitor of cellular immune

activation in transplantation, inflammatory, infectious and malignant diseases. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1992; 29:304-41.

4. Fuchs D, Weiss G, Wachter H. Neopterin, biochemistry and clinical use as a marker for cellular immune

reactions. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1993; 101:1-6.

5. Wachter H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Weiss G, Werner-Felmayer G. Neopterin: Biochemistry-

Methods-Clinical Application, Walter deGruyter, Berlin, New York, 1992.

6.Fuchs D, Wachter H. Neopterin. In: Labor und Diagnose, Thomas L., ed. Die Medizinische

Verlagsgesellschaft, Marburg/Lahn,1997.

7.Huber C, Batchelor JR, Fuchs D, et al. Immune response-associated production of neopterin - Release

from macrophages primarily under control of interferon-gamma. J Exp Med 184;160:310-6.

8.Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Fuchs D, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthetic activities in human

macrophages, fibroblasts, THP-1 and T 24 cells. GTP-cyclohydrolase I is stimulated by interferon-gamma, 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase and sepiapterin reductase are constitutively present. J Biol Chem 1990;265:3189-92.

9.Werner-Felmayer G, Werner ER, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Wachter H. Neopterin formation

and tryptophan degradation by a human myelomonocytic cell line (THP-1). Cancer Res 1990;50:2863-7.

10.Nachbaur K, Troppmair J, Bieling P, Kotlan B, König P, Huber Ch. Cytokines in the control of beta-2

microglobulin release. 1. In vitro studies on various haemopoietic cells. Immunobiology 1988;177:55-6.

11.Werner-Felmayer G, Werner ER, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Wachter H. Tumour necrosis factor-

alpha and lipopolysaccharide enhance interferon-induced tryptophan degradation and pteridine synthesis in human cells. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 1989;370:1063-9.

12.Maggi E, Parronchi P, Manetti R, et al. Reciprocal regulatory role of IFN-γ and IL-4 on the in vitro

development of human Th1 and Th2 clones. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2142-8.

13. Diez-Ruiz A, Tilz GP, Zangerle R, Baier-Bitterlich G, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Soluble receptors for tumor

necrosis factor in clinical laboratory diagnosis. Eur J Haematol 1995,54:1-8.

14.Niederwieser A, Curtius HC, Bettoni O, et al. Atypical phenylketonuria caused by 7,8-dihydroneopterin

synthetase deficiency. Lancet 1979;1: 131-3.

15.Fuchs D, Baier-Bitterlich G, Wede I, Wachter H. Reactive oxygen and apoptosis. In: Oxidative stress and

the molecular biology of antioxidant defenses. Scandalios J, ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 1966: 139-67.

16.Nathan CF. Perodxide and pteridine: a hypothesis of the regulation of macrophage antimicrobial activity

by interferon-gamma. In: Interferon, vol.7, Gresser J, ed., Academic Press, London, 1986;125-43.

17.Weiss G, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Neopterin modulates toxicity mediated by reactive oxygen and

chloride species. FEBS Lett 1993;321:89-92.

18.Wede I, Baier-Bitterlich G, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Effects of neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin on luminol-

dependent chemiluminescence induced by reactive intermediates formed from hydrogen peroxide, chloramine-T, hypochloride and nitrite. Pteridines 1995;6:35.

19.Schneemann M, Schoedon G, Hofer S, Blau N, Guerrero L, Schaffner A. Nitric oxide is not a constituent

of the antimicrobial armature of humen mononuclear phagocytes. J Infect Dis 1993;167:1358-63.

20.Fuchs D, Murr C, Reibnegger G, et al. Nitric oxide synthase and antimicrobial armature of human

macrophages. J Infect Dis 1994:169;224.

21.Widner B, Baier-Bitterlich G, Wede I, Wirleitner B, Fuchs D. Neopterin derivatives modulate the nitration

of tyrosine by peroxynitrite. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 1998;248:341-6.

22.Wirleitner B, Bitterlich-Baier G, Hoffman G, Schobersberger W, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Neopterin-

derivatives to activate NF-KB. Free Radical Biol Med 1997;23:177-8.

23.Hoffmann G, Schobersberger W, Frede S, et al. Neopterin activates transcription factor nuclear factor-kB

in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett 1996; 391:181-4.

24.Schobersberger W, Hoffmann G, Grote J, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Induction of inducible nitric oxide

synthase expression by neopterin in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett 1995;377:461-4.

25.Baier-Bitterlich G, Fuchs D, Murr C, et al. Effect of 7,8-neopterin on tumor necrosis factor-α induced

programmed cell death. FEBS Lett 1995;95:227-32.

26.Schobersberger W, Hoffmann G, Hobisch-Hagen, et al. Neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin induce

apoptosis in the rat alveolar epithelial cell line L2. FEBS Lett 1996;397:263-8.

27.Schobersberger W, Jelkmann W, Fandrey J, Frede S, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Neopterin-induced

suppression of erythropoietin production in vitro. Pteridines 1995;6:12-6.

28.Überall F, Werner-Felmayer G, Schubert C, Grunicke HH, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Neopterin derivatives

together with cyclic guanosine monophosphate induce c-fos gene expression. FEBS Lett 1994;352:11-4.

29.Fuchs D, Werner ER, Wachter H. Soluble products of immune activation: Neopterin. In: Rose RR,

deMacario EC, Fahey JL, Friedman H, Penn GM. eds. Manual of Clinical Laboratory Immunology. 4th ed. Washington, D.D., American Society for Microbiology, 1992;251-5.

30.Fuchs D, Stahl-Hennig C, Gruber A, Murr C, Hunsmann G, Wachter H. Neopterin - its clinical use in

urinalysis. Kydney Int 1994;46:8-11.

31.Werner ER, Bichler A, Daxenbichler G, et al. Determination of neopterin in serum and urine. Clin Chem

32.Mayersbach P, Augustin R, Schennach H, et al. Commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for

neopterin detection in blood donations compared with RIA and HPC. Clin Chem 1994;40:265-6.

33.Hausen A, Aichberger C, Königsrainer A, et al. Biliary and urinary neopterin concentrations in monitoring

liver allograft recipients. Clin Chem 1993;39:45-7.

34.Hagberg L, Dotevall L, Norkrans G, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Cerebrospinal fluid neopterin concentrations in

central nervous system infection. J Infect Dis 1993;168:1285-8.

35.Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Dittrich P, Wachter H. Neopterin levels in long term

hemodyalisis. Clin Nephrol 1988;177:1-6.

36.Reibnegger G, Auhuber I, Fuchs D, et al. Urinary neopterin levels in acute viral hepatitis. Hepatology

37.Kern P, Rokos H, Dietrich M. Raised serum levels and imbalances of T-lymphocyte subsets in viral

diseases, acquired immune deficiency and related lymphadenopathy syndromes. Biomed Pharmacother 1984;38:407-11.

38.Griffin DE, Ward BJ, Jauregui E, Johnson RT, Vaisberg A. Immune activation during measles: interferon

gamma and neopterin in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in complicated and uncomplicated disease. J Infect Dis 1990;161:449-53.

39.Prior C, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Potential of urinary neopterin excretion differentiating chronic non-A,

non-B hepatitis from fatty liver. Lancet 1987; ii:1235-7.

40.Tilg H, Margreiter R, Scriba M, et al. Clinical presentation of CMV infection in solid organ transplant

recipients and its impact on graft rejection and neopterin excretion. Clin Transplantation 1987;1:37-43.

41.Zaknun D, Weiss G, Glatzl J, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Neopterin levels during acute rubella in children. Clin

Infect Dis 1993;17:521-2.

42.Zangerle R, Schönitzer D, Fuchs D, Möst J, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Reducing HIV transmission by

seronegative blood. Lancet 1992;339:130-1.

43.Fuchs D, Spira TJ, Hausen A, et al. Neopterin as a predictive marker for disease progression in human

immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin Chem 1989;35:1746-9.

44.Fahey JL, Jeremy MD, Taylor MG, et al. The prognostic value of cellular and serologic markers in

infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. New Engl J Med 1990;322:166-72.

45.Fendrich C, Lüke W, Stahl-Hennig C, et al. Urinary neopterin concentrations in rhesus monkeys after

infection with simian immunodeficiency virus mac strain 251. AIDS 1989;3:305-7.

46.Krämer A, Biggar RJ, Hampl H, et al. Immunologic markers of progression to acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome are time-dependent and illness-specific. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136:71-80.

47.Zangerle R, Sarcletti M, Möst J, Steinhuber S, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Serum HIV-1 RNA levels compared

to soluble markers of immune activation to predict disease progression in HIV-1 infected individuals. Pteridines 1996;7:67-8.

48.Hagberg L, Norkrans G, Gisslen M, Wachter H, Fuchs D, Svennerholm B. Intrathecal immunoactivation in

patients with HIV-1 infection is reduced by zidovudine but not by didanosine. Scand J Infect Dis 1996;28:329-33.

49. Hutterer J, Armbruster C, Wallner G, Fuchs D, Vetter N, Wachter H. Early changes of neopterin

concentrations during treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection with zidovudine. J Infect Dis 1992;165:783-4.

50.Fuchs D, Albert J, Asjö B, Fenyö EM, Reibnegger G, Wachter H: Association between serum neopterin

concentrations and in vitro replicative capacity of HIV-1 isolates. J Infect Dis 1989;160:724-5.

51.Fuchs D, Zangerle R, Artner-Dworzak E, et al. Association between immune activation, changes of iron

metabolism and anaemia in patients with HIV-infection. Eur J Haematol 1993;50:90-4.

52.Zangerle R, Fuchs D, Reibnegger G, Fritsch P, Wachter H: Markers for disease progression in

intravenous drug users infected with HIV-1. AIDS 1991;5:985-91.

53.Baier-Bitterlich G, Fuchs D, Zangerle R, et al. Transactivation of the HIV-1 promoter by 7,8-

dihydroneopterin in vitro. AIDS Res Human Retrovir 1997;13:173-8.

54.Baier-Bitterlich G, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Role of neopterin and 7,8-dihydroneopterin in human

immunodeficiency virus infection: marker for disease progression and pathogenic link. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1996;13:184-93.

55.Fuchs D, Chiodi F, Albert J, et al. Neopterin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of individuals

infected with HIV-1. AIDS 1989;3:285-8.

56.Brew BJ, Bhalla RB, Paul M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neopterin in human immunodeficiency virus type 1

infection. Ann Neurol 1990:28:556-60.

57.Fuchs D, Hausen A, Kofler M, Kosanowski H, Reibnegger R, Wachter H: Neopterin as an index of

immune response in patients with tuberculosis. Lung 1984;162:337-46.

58.Hosp M, Elliott AM, Raynes JG, et al. Neopterin, beta-2-microglobulin, and acute phase proteins in HIV-1

seropositive and seronegative Zambian patients with tuberculosis. Lung (in press).

59.Schmutzhard E, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Wachter H. Is neopterin, a marker of cell mediated

immune response, helpful in classifying leprosy. East Afr Med J 1986;63:577-80.

60.Brown AE, Dance DAB, Chaowagul W, Webster HK, White NJ. Activation of immune responses in

melioidosis patients as assessed by urinary neopterin. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1990;84:583-4.

61.Reibnegger G, Boonpucknavig V, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Schmutzhard E, Wachter H. Urinary neopterin is

elevated in patients with malaria. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 1984;78:545-6.

62.Kern P, Hemmer CJ, Van Damme J, Gruss HJ, Dietrich M. Elevated tumor necrosis factor alpha and

interleukin-6 serum levels as markers for complicated plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Med 1989;87:139-43.

63.Zwingenberger K, Harms G, Feldmeier H, Müller O, Steiner A. Liver involvement in human

schistosomiasis. Acta Tropica 1988;45:263-75.

64.Brown AE, Herrington DA, Webster HK, et al. Urinary neopterin in volunteers experimentally infected with

plasmodium falciparum. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992;86:134-6.

65.Denz H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Value of urinary neopterin in the differential diagnosis of bacterial and

viral infections. Klin Wochenschr 1990;68:218-22.

66.Strohmaier W, Redl H, Schlag G, Inthorn D. D-erythro-neopterin plasma levels in intensive care patients

with and without septic complications. Crit Care Med 1987;15:757-60.

67.Uomo G, Spada OA, Manes G, et al. Neopterin in acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol

68.Hagberg L, Norkrans G, Andersson M, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Cerebrospinal fluid neopterin and ß2-

microglobulin levels in neurologically asymptomatic HIV-infected patients before and after initiation of zidovudine treatment. Infection 1992;20:313-5.

69.Kölfen W, Korinthenberg R, Teuber J. Intrathecal production of neopterin in meningitis in childhood. Klin

Paediatr 1990;202:399-403.

70.Zaknun D, Zaknun J, Unsinn K, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Interferon gamma-induced formation of neopterin

and degradation of tryptophan in cerebrospinal fluid of children with meningitis but not with febrile convulsions. Pteridines 1994;5:102-6.

71.Reibnegger G, Egg D, Fuchs D, et al. Urinary neopterin reflects clinical activity in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1063-70.

72.Märker-Alzer D, Diemer O, Strümper R, Rohe M. Neopterin production in inflamed knee joints: high levels

in synovial fluids. Rheumatol Int 1986;6: 151-4.

73.Samsonov MY, Tilz GP, Egorova O, et al. Serum soluble markers of immune activation and disease

activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 1995;4:29-32.

74.Lim KL, Jones AC, Brown NS, Powell RJ. Urine neopterin as a parameter of disease activity in patients

with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparisons with serum sIL-2R and antibodies to dsDNA, erythocyte sedimentation rate, and plasma C3, C4, and C3 degradation products. 1993;52:429-35.

75.Nassonov EL, Nassonov L, Mikhail Y, et al. Serum concentrations of neopterin, soluble interleukin-2

receptor and soluble TNF receptor in Wegener's granulomatosis. J Rheumatol (in press).

76.Samsonov MY, Nassonov EL, Tilz GP, et al. Elevated serum levels of neopterin in adult patients with

polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Brit J Rheumatol (in press).

77.Reibnegger G, Bollbach R, Fuchs D, et al. A simple index relating clinical activity in Crohn's disease with

T cell activation: Hematocrit, frequency of liquid stools and urinary neopterin as parameters. Immunobiology 1986;173:1-11.

78.Niederwieser D, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Neopterin as a new biochemical marker in the clinical

assessment of ulcerative colitis. Immunobiol 1985;170:320-6.

79.Fuchs D, Granditsch G, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Wachter H: Urinary neopterin excretion in coelicac

disease. Lancet 1983; ii:463-4.

80.Prior C, Frank A, Fuchs D, et al. Immunity in sarcoidosis. Lancet 1987; ii:741. 81.Fredrikson S, Link H, Eneroth P. CSF neopterin as marker of disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Acta

Neurol Scand 1987;75:352-5.

82.Westarp ME, Fuchs D, Bartmann P, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - an enigmatic disease with B-

cellular and anti-retroviral immune responses. Eur J Med 1993;2:327-32.

83.Samsonov M, Fuchs D, Reibnegger G, Belenkov JN, Nassonov EL, Wachter H. Patterns of serological

markers for cellular immune activation in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic myocarditis. Clin Chem 1992;38:678-80.

84.Iizuka T, Minatogawa Y,Suzuki H, et al. Urinary neopterin as a predictive marker of coronary artery

abnormalities in kawasaki syndrome. Clin Chem 1993;39/4:600-4.

85.Samsonov MY, Tilz GP, Pisklakov VP, et al. Serum-soluble receptors for tumor necrosis factor-α and

interleukin-2, and neopterin in acute rheumatic fever.Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1995;74:31-4.

86.Weiss G, Willeit J, Kiechl S, et al. Increased concentrations of neopterin in carotid atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis 1994;106:263-71.

87.Melichar B, Gregor J, Solichova D, Lukes J, Tichy M, Pidrman V. Increased urinary neopterin in acute

myocardial infarction. Clin Chem 1994;40:338-9.

88.Reibnegger G, Fuchs D, Fuith LC, et al. Neopterin as a marker for activated cell-mediated immunity:

Application in malignant disease. Cancer Detect Prevent 1991;15:483-90.

89.Reibnegger GJ, Bichler AH, Dapunt O, et al. Neopterin as a prognostic indicator in patients with

carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer

Res 1986;46:950-5.

90.Reibnegger G, Hetzel H, Fuchs D, et al. Clinical significance of neopterin for prognosis and follow-up in

ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 1987; 47:4977-81.

91.Lewenhaupt A, Ekman P, Eneroth P, Eriksson A, Nillson B, Nordström L. Serum levels of neopterin as

related to the prognosis of human prostatic carcinoma. Eur Urol 1986;12:422-5.

92.Kawasaki H, Watanabe H, Yamada S, Watanabe K, Suyama A. Prognostic significance of urinary

neopterin levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tohoku J Exp Med 1988;155:311-8.

93.Denz H, Fuchs D, Huber H, et al. Correlation between neopterin, interferon-gamma and haemoglobin in

patients with haematological disorders. Eur J Haematol 1990;44:186-9.

94.Denz H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Value of urinary neopterin in the differential diagnosis of bacterial and

viral infections. Klin Wochenschr 1990;68:218-22.

95.Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, et al. Immune activation and the anaemia associated with chronic

inflammatory disorders. Eur J Haematol 1991;46:65-70.

96.Margreiter R, Fuchs d, Hausen A, et al. Neopterin as a new biochemical marker for diagnosis of allograft

rejection. Transplantation 1983;36:650-3.

97.Reibnegger G, Aichberger C, Fuchs D, et al. Posttransplant neopterin excretion in renal allograft

recipients - A reliable diagnostic aid for acute rejection and a predictive marker of long - term graft survival. Transplantation 1991;52:58-63.

98.Königsrainer A, Reibnegger G, Öfner D, Klima G, Tauscher T, Margreiter R. Pancreatic juice neopterin

excretion - reliable marker for detection of pancreatic allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:671-2.

99.Niederwieser D, Huber C, Gratwohl A, et al. Neoptein as a new biochemical marker in the clinical

monitoring of bone marrow transpla recipients. Transplantation 1984;38:497-500.

100.Gastl G, Aulitzky W, Tilg H, et al. A biological approach to optimize interferon treatment in hairy cell

leukemia. Immunobiology 1986;172:262-8.

101.Hönlinger M, Fuchs D, Hausen A, et al. Serum-Neopterinbestimmung zur zusätzlichen Sicherung der

Bluttransfusion. Deutsch Med Wochenschr 1989; 114:172-6.

102.Hönlinger M, Fuchs D, Reibnegger G, Schönitzer D, Dierich MP, Wachter H. Neopterin screening and

acute cytomegalovirus infections in blood donors. Clin Investig 1992;70:63.

103.Schennach H, Mayersbach P, Schönitzer D, Fuchs D, Wachter H, Reibnegger G. Increased prevalence

of IgM antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19 in blood donations with above-normal neopterin concentration. Clin Chem 1994;40: 2104-5.

104.Peters KM, Leusch HG, Bruchhausen B, Schilgen M, Markos-Pusztai S. neopterin determinations in the

screening for spongiosa donors. Z Orthop Grenzb 1990;128:453-6.

Source: http://www.neopterin.net/neopterin_e.pdf

Document downloaded from http://www.revespcardiol.org, day 07/10/2016. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Rosuvastatin and Metformin Decrease Inflammation andOxidative Stress in Patients With Hypertension and DyslipidemiaAnel Gómez-García,a Gloria Martínez Torres,b Luz E. Ortega-Pierres,c Ernesto Rodríguez-Ayala,band Cleto Álvarez-Aguilard

Chen et al. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 2012, 31:4http://www.jphysiolanthropol.com/content/31/1/4 Herbs in exercise and sports Chee Keong Chen*, Ayu Suzailiana Muhamad and Foong Kiew Ooi The use of herbs as ergogenic aids in exercise and sport is not novel. Ginseng, caffeine, ma huang (also called‘Chinese ephedra'), ephedrine and a combination of both caffeine and ephedrine are the most popular herbs usedin exercise and sports. It is believed that these herbs have an ergogenic effect and thus help to improve physicalperformance. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of these herbs on exerciseperformance. Recently, researchers have also investigated the effects of Eurycoma longifolia Jack on endurancecycling and running performance. These investigators have reported no significant improvement in either cyclingor running endurance after supplementation with this herb. As the number of studies in this area is still small,more studies should be conducted to evaluate and substantiate the effects of this herb on sports and exerciseperformance. For instance, future research on any herbs should take the following factors into consideration:dosage, supplementation period and a larger sample size.