Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Somnomedics.de

Author's personal copy

Psychiatry Research 189 (2011) 62–66

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Psychiatry Research

Schizophrenia patients with predominantly positive symptoms have more disturbed

sleep–wake cycles measured by actigraphy

Pedro Afonso a,⁎, Sofia Brissos a, Maria Luísa Figueira b, Teresa Paiva ba Lisbon's Psychiatric Hospitalar Center (CHPL), Lisbon, Portugalb Hospital Santa Maria, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, (FMUL), Lisbon, Portugal

Sleep disturbances are widespread in schizophrenia, and one important concern is to determine the impact of

Received 28 February 2010

this disruption on self-reported sleep quality and quality of life (QoL). Our aim was to evaluate the sleep–wake

Received in revised form 20 December 2010

cycle in a sample of patients with schizophrenia (SZ), and whether sleep patterns differ between patients with

Accepted 31 December 2010

predominantly negative versus predominantly positive symptoms, as well as its impact on sleep quality andQoL. Twenty-three SZ outpatients were studied with 24 h continuous wrist-actigraphy during 7 days. The

quality of sleep was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the self-reported QoL was

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

evaluated with the World Health Organization Quality of Life — Abbreviated version (WHOQOL-Bref). About

half of the studied population presented an irregular sleep–wake cycle. We found a trend for more disrupted

Negative symptoms

sleep–wake patterns in patients with predominantly positive symptoms, who also had a trend self-reported

worse quality of sleep and worse QoL in all domains. Overall, patients with worse self-reported QoLdemonstrated worse sleep quality. Our findings suggest that SZ patients are frequently affected with sleep andcircadian rhythm disruptions; these may have a negative impact on rehabilitation strategies. Moreover, poorsleep may play a role in sustaining poor quality of life in SZ patients.

2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Although sleep architecture improves with antipsychotic treatment,

sleep remains mostly fragmented and fails to establish its normal

Sleep is an important restorative physiologic process (Suresh Kumar

pattern (Kupfer et al., 1970). This suggests that sleep physiology might

et al., 2007). The sleep–wake cycle is a circadian rhythm generated and

share a common substrate with SZ symptoms (Boivin, 2000; Poulin

regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus,

et al., 2003; Cohrs, 2008). Furthermore, worse sleep quality has been

synchronized by internal (body) and external (environment) stimuli

associated with poorer quality of life (QoL), even after correcting for

(Albrecht, 2002; Van Gelder, 2004).

depression and drug effects (Hofstetter et al., 2005; Ritsner et al., 2004).

Patients with schizophrenia (SZ) frequently experience sleep

Positive and negative symptoms, neurocognitive impairment and brain

problems (Keshavan et al., 1990; Taylor et al., 1991; Tandon et al.,

structure may also correlate with important sleep variables such as sleep

1992; Monti and Monti, 2004; Cohrs, 2008), like advanced sleep phase

latency, sleep efficiency, SWS, and REM sleep parameters (Cohrs, 2008).

syndrome and hypersomnia with short naps (Wirz-Justice et al.,

REM density was inversely correlated with positive, cognitive, and

2001). Reduced sleep efficiency and total sleep time, increased sleep

emotional discomfort symptoms as well as the total score on the Positive

latency, decrease in slow wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement

and Negative Syndrome Scale (Yang and Winkelman, 2006).

(REM) latency have also been reported in most patients with SZ

However, because of the limited number of methodologically

(Tandon et al., 1992; Zarcone et al., 1987; Keshavan et al., 1998). This is

rigorous studies, no clear statement can be made about the influence

especially true during psychotic episodes (Kupfer et al., 1970), but also

of these variables on sleep structure (Cohrs, 2008). Actigraphy has been

in the prodromal phase (Donlon and Blacker, 1975; Cohrs, 2008).

used in SZ to study sleep and circadian rhythms (Haug et al., 2000;

It remains unclear whether sleep problems in SZ are secondary

Poyurovsky et al., 2000; Shamir et al., 2000; Hofstetter et al., 2005;

to social withdrawal and reclusive behavior, to medication, or to an

Martin et al., 2005; Wulff et al., 2006), but studies have been limited,

abnormality of the neuroendocrine systems regulating sleep and

probably for methodological feasibility reasons (Vanelle, 2009).

wakefulness (Wulff et al., 2006).

One of the most important goals in SZ treatment is social and

professional rehabilitation. To accomplish this, physiologic sleep,compatible with work routines and timetables is necessary.

We aimed to evaluate the sleep–wake cycle in a sample of SZ

⁎ Corresponding author. Lisbon Psychiatry Hospital Center, Av. do Brasil n°. 53, 1749-

002 Lisbon, Portugal. Tel.: +351 217917000; fax: +351 217 952 989.

patients, and whether sleep patterns differed between patients with

E-mail address: [email protected] (P. Afonso).

predominantly negative versus predominantly positive symptoms.

0165-1781/$ – see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.031

Author's personal copy

P. Afonso et al. / Psychiatry Research 189 (2011) 62–66

Moreover, we hypothesized that worse quality and sleep patterns,

would be associated with poorer self-reported QoL.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

2. Material and methods

positive symptoms)

negative symptoms)

2.1. Participants

Gender (men:women)

Data herein reported is based on an ongoing investigation on sleep characteristics

of SZ patients at Lisbon's Psychiatric Hospital Center. Twenty-three patients with SZ,aged 19–52 yrs, were diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 2000), ascertained

from interview with a psychiatrist and medical chart review. Patients were evaluated

with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale — PANSS (Kay et al., 1989). Based on

Educational level (yrs)

the PANSS scores, patients were divided into two groups according to symptom

Illness duration (yrs)

preponderance: Group 1 (n = 11) included patients with predominant positive

Number of admissions

symptoms, and Group 2 (n= 12) included patients with predominant negative

Legend: yrs: years; S.D.: standard deviation.

⁎ p b0.05.

At the time of evaluation all patients had been on a stable medication regimen for at

least 1 month. Patients taking benzodiazepines in daily doses lower than the equivalentof diazepam 15 mg (never taken after 18h00) were accepted. A minimum washoutperiod of 72 h was obligatory for hypnotic medication. The daily dosage of

(iii) mean duration (s) of uninterrupted immobility (MIP)(activity =0). The mean

antipsychotics and diazepam used in each treatment group was as follows. (1) Group

duration of uninterrupted immobility periods (MIP) provides a global measure

1; olanzapine (n=4), mean 18.8 mg; quetiapine (n=1), mean 600 mg; risperidone

of the distribution and number of immobility periods.

(n=3), mean 6 mg; clozapine (n=3), mean 367 mg; diazepam (n=2) mean 7.5 mg;(2) Group 2: olanzapine (n=4), mean 17.5 mg; quetiapine (n=1), mean 400 mg;

2.4. Statistical analysis

risperidone (n=2), mean 4.5 mg; clozapine (n=4), mean 362.5 mg; ziprasidone(n=1), mean 120 mg; diazepam (n=3) mean 8.3 mg.

Both groups were compared in sociodemographic, and clinical variables using

Schizoaffective disorder, organic impairment, previous head trauma or neurolog-

nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, Chi-Square and contingency (symmetry). Correla-

ical disorders, or substance abuse/dependence were considered exclusion criteria.

tions of sociodemographic and clinical variables, WHOQOL-BREF, PSQI, and actigraphy

Patients working night-shifts were also excluded.

data were calculated through Spearman correlation. We used SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc.,

The local Ethics committee approved the study, and all participants provided

Chicago, IL, USA).

written informed consent.

2.2. Assessment instruments

The quality and patterns of sleep were measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality

Social, demographic, and clinical characteristics of our sample are

Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989). This self-report questionnaire rates sleep quality and

presented in Table 1. Significant statistical differences were found

patterns during the previous month, and evaluates 7 components of sleep: subjective

only in professional activity, patients with preponderant negative

quality, latency, duration, usual efficiency, sleep disturbances, medication use, anddaytime dysfunction. The score is given through a Likert-like scale, between 0 and 3,

symptoms being all inactive.

with a cut-off value of 5, higher scores meaning worse sleep quality.

There was no difference in PANSS total (Group 1, mean 89.4, S.D.

Subjective quality of life (QoL) was assessed using the WHO Quality of Life Measure —

19.3; Group 2, mean 82, S.D. 22.6) or general psychopathology results

Abbreviated version (WHOQOL–BREF–PT), Portuguese version. The 26-item version

between both groups (Group 1, mean 48.5, S.D. 10.5; Group 2, mean

WHOQOL–BREF (W.H.O.Q.O.L. Group, 1994) provides measurement on four domains:

44, S.D. 11.0). Because of the patients' allocation, the positive

physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment. Higher scores meanbetter QoL.

symptom's PANSS subscale results were higher in Group 1 (mean

Wrist-actigraphy was used for sleep–wake cycle assessment. Actigraphy provides

24.2, S.D. 5.4) than in Group 2 (mean 12.3, S.D. 3.2). On the other

the recording of continued limb motor activity during 24 h or longer periods and is a

hand, negative symptom's PANSS subscale results were higher in the

useful and validated instrument for sleep studies (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2003). Actimeters

latter (mean 26.1, S.D. 9.2) than in Group 1 (mean 16.6, S.D. 5.2). For

(SomnoWatch® actigraphy system) were strapped on the patients' nondominantwrists. Movement counts of the actigraph were stored in 1 second interval, with the

these results, there was statistical significance.

signal sampled at 32 Hz with 12 Bit ADC, allowing continuous recording for 168 h

Both groups presented a score above of 5 on the PSQI, which is

(7 days) on the 16 MB memory. We chose the smallest possible interval to achieve

considered as poor sleep quality (Table 2). Group 2 subjects self-

maximum temporal resolution. Since actigraphy cannot distinguish between sleep and

reported better QoL in all domains, compared to Group 1, but the

sedentary activities, subjects recorded in a diary, bed and wake times, awakenings

differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

at night, day naps, and other activities. During the study period all participants usedthe equipment at all times, except when bathing. In these situations we asked

No significant differences were found in motor activities measure-

the participants to mark this period by pressing a button to mark events on the

ments during wakefulness (day) and sleep (night) between the two

SomnoWatch® (before and after bathing). Data during these periods were treated as

groups (Table 3).

2.3. Sleep/wake variables and actigraphic parameters

Table 2Quality of sleep and quality of life in both patient groups.

Sleep latency was considered as the time period between turning-off the light and

falling asleep. The actigraph contains a light sensor that measures the time between the

instant when the light goes off and the reduction of motor activity (typical of sleep

onset). To score sleep onset we used the 5 min of actigraphic immobility criterion (Chae

positive symptoms) negative symptoms) Test

et al., 2009). To assess sleep–wake cycles the actogram was visually analysed and

confronted with the sleep log information given by the patients. The sleep–wakerhythm was considered regular when there was a clear distinction between sleep/

inactivity occurring at night and wake/activity periods occurring during the day, and

regular occurrences of both during the week.

Using the sleep log information, and the light sensor information, we divided the

WOQOL — physical

data between night (period between lights off and wake) and day period. Data were

transferred to our own EXCEL® templates for further analyses. We chose to extract

WOQOL — psychological

three variables from the data that had previously been described (Middelkoop et al.,

1997). Actigraphy measures were calculated as follows:

WOQOL — social domain 40.4 (20.7)

WOQOL — environmental 59.7 (17.5)

(i) movement index (MI) (%), indicating the percentage of epochs with an activity

Legend: PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; WHOQOL: World Health Organization

(ii) activity level (AL), number of activity counts per hour.

Quality of Life.

Author's personal copy

P. Afonso et al. / Psychiatry Research 189 (2011) 62–66

Actigraphy results between the patient groups.

Our results show that there is a trend for more disrupted sleep–

wake patterns and circadian activity rhythms in SZ patients with

positive symptoms)

negative symptoms)

predominant positive symptoms. In fact, Group 1 patients self-

reported worse quality of sleep as compared to Group 2, except forone item (hypnotic use). Moreover, Group 1 patients self-reported

Sleep latency (min)

Movement index (%)

worse QoL in all domains as compared to patients with predominant

negative symptoms, indicating that worse sleep patterns may lead

to worse subjective quality of sleep and QoL. Our results support

Activity level (number of counts/hour)

previous findings that SZ patients show more disrupted sleep–wake

patterns and circadian activity compared to healthy subjects (Martin

Uninterrupted immobility duration (s)

et al., 2005).

An important aspect in actigraphy results was sleep latency; in both

groups sleep latency proved to be quite long (usually, sleep latency

Regular sleep–wake

should take about 30 min), as confirmed by the patients' subjective

opinion of worse quality of sleep.

Legend: min: minutes; s: seconds; S.D.: standard deviation.

We found differences, although not statistically significant,

b Chi-square test.

between the groups regarding regular sleep–wake rhythms; 11 outof 23 subjects showed an irregular sleep–wake rhythm. We verified arelative absence of a circadian pattern of the sleep–wake cycle. The

Group 1 presented worse actigraphy patterns with 7 patients (64%)

actogram and the sleep log showed that sleep times were randomly

presenting an irregular sleep–wake cycle (Fig. 2) and only 4 patients

distributed throughout the day and night and sleep duration and

showing regular sleep–wake cycles (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Sleep latency

wake-up episodes were variable and unpredictable during the 24 h

was higher in Group 1 (Table 3), but these differences were not

period. Actigraphy confirmed daytime napping and nighttime

statistically significant. Only 36% of Group 1 patients presented

fragmentation, a common finding in SZ patients (Yamadera et al.,

normal alternation between sleep/wake states, as compared to 67%

in Group 2; however, these differences were not statistically significant.

We found a significant association between psychopathology and

In Group 2, 4 patients (33%) presented irregular sleep–wake pattern,

general symptoms, and quality of sleep, but no significant correlations

while 8 showed regular sleep–wake cycles; these differences were

with positive and negative symptoms, and quality of sleep. Other

not significant (Chi2=2.112; p=0.220), but the contingency analysis

symptoms, namely depressive, could possibly influence more the

showed symmetry among them (p=0.146).

quality of sleep, than positive or negative symptoms. We were able to

Significant negative correlations were found between PANSS sub-

replicate earlier findings showing that in schizophrenia self-reported

scales' scores and WHOQOL-BREF and PSQI scores, indicating that

QoL is associated with quality of sleep (Ritsner et al., 2004; Hofstetter

higher symptom levels correlate with lower self-reported QoL and

et al., 2005; Xiang et al., 2009). In our sample, patients with

worse quality of sleep (Table 4). However, we found no significant

predominant negative symptoms reported better quality of sleep

correlations between sleep/wake variables and quantitative motor

and better QoL. Patients with negative syndrome present low motor

activity on actigraphy, and scores on any PANSS subscales, and/or any

activity levels (Walther et al., 2009), possibly facilitating sleep. On the

QoL domain (data not shown).

other hand, hallucinations and delusions may cause difficulty in falling

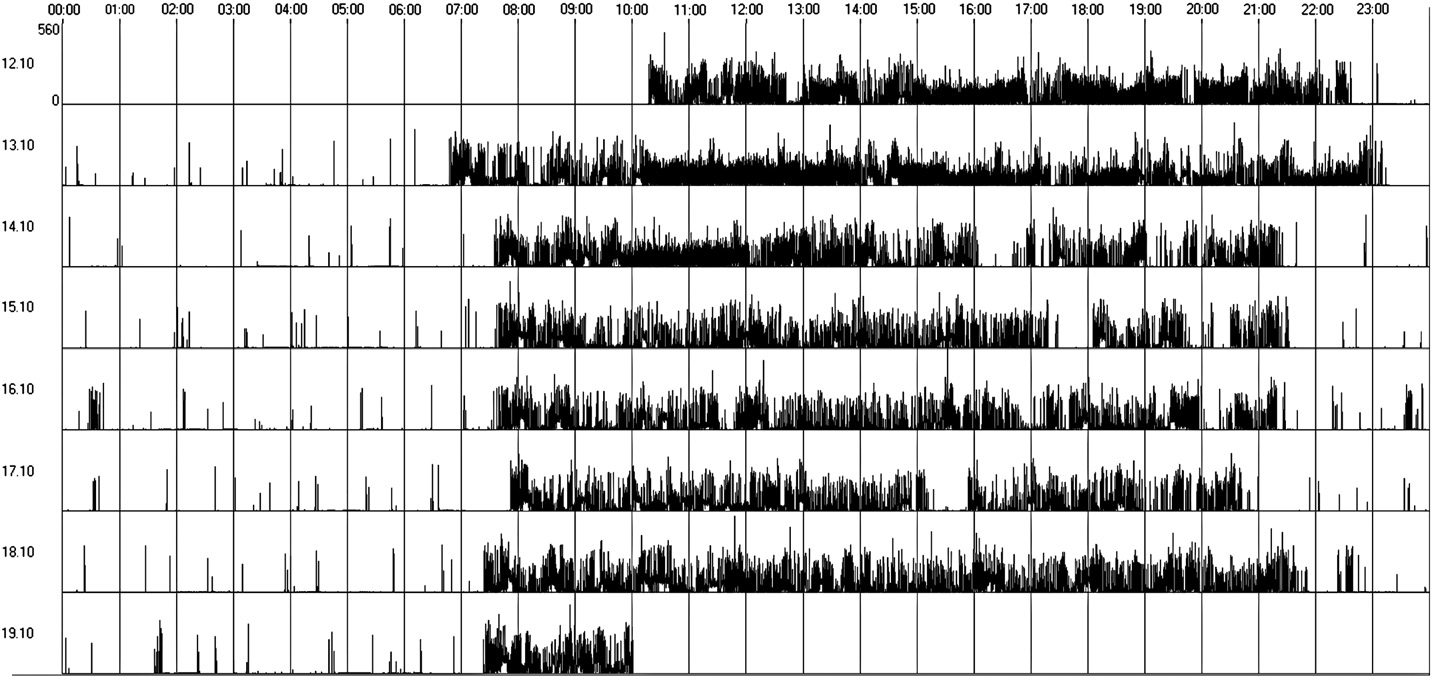

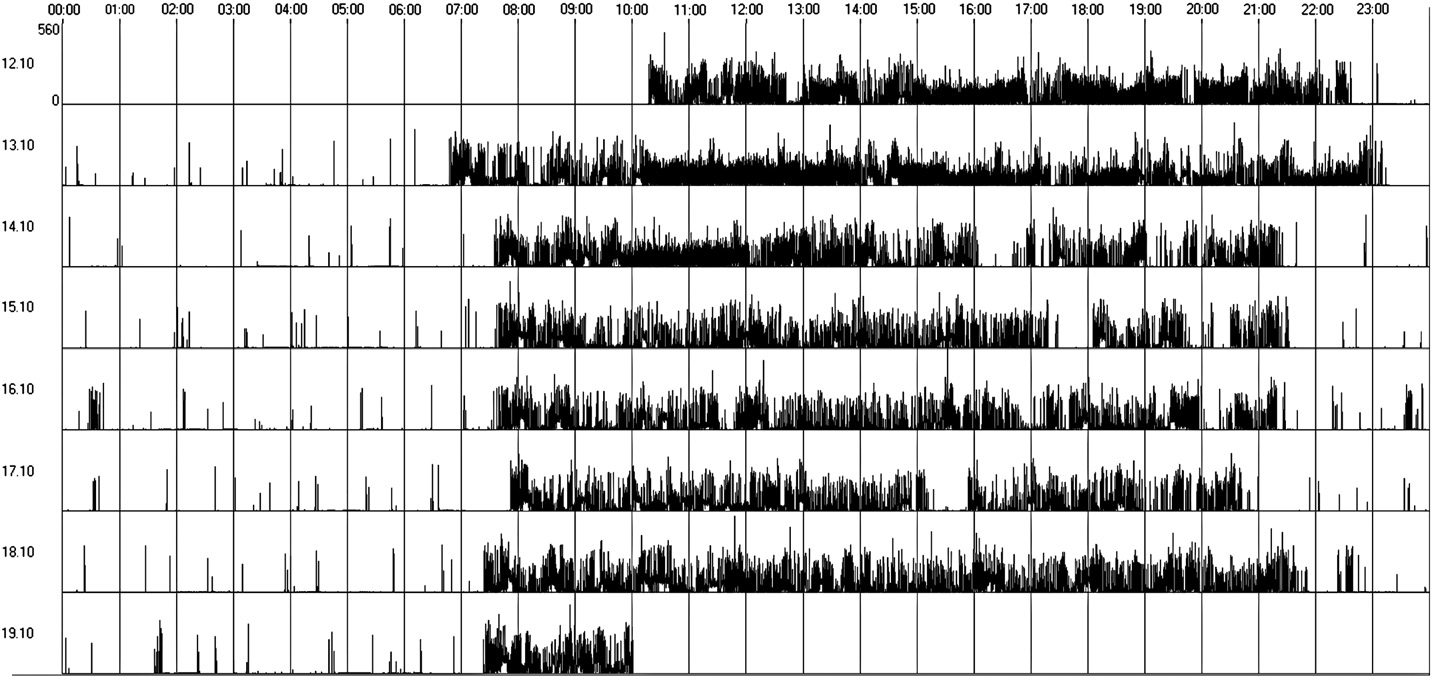

Fig. 1. Regular sleep–wake rhythm (actogram obtained by actigraphy over a 7-day period).

Author's personal copy

P. Afonso et al. / Psychiatry Research 189 (2011) 62–66

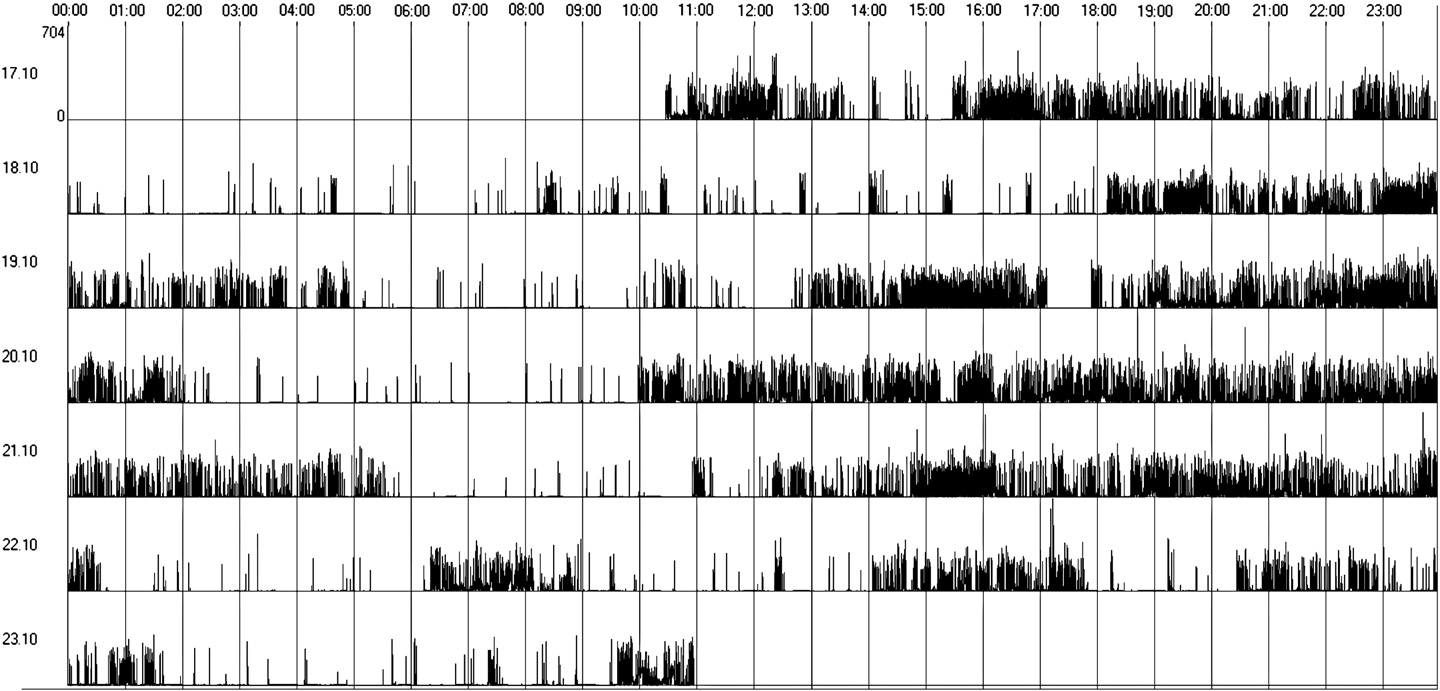

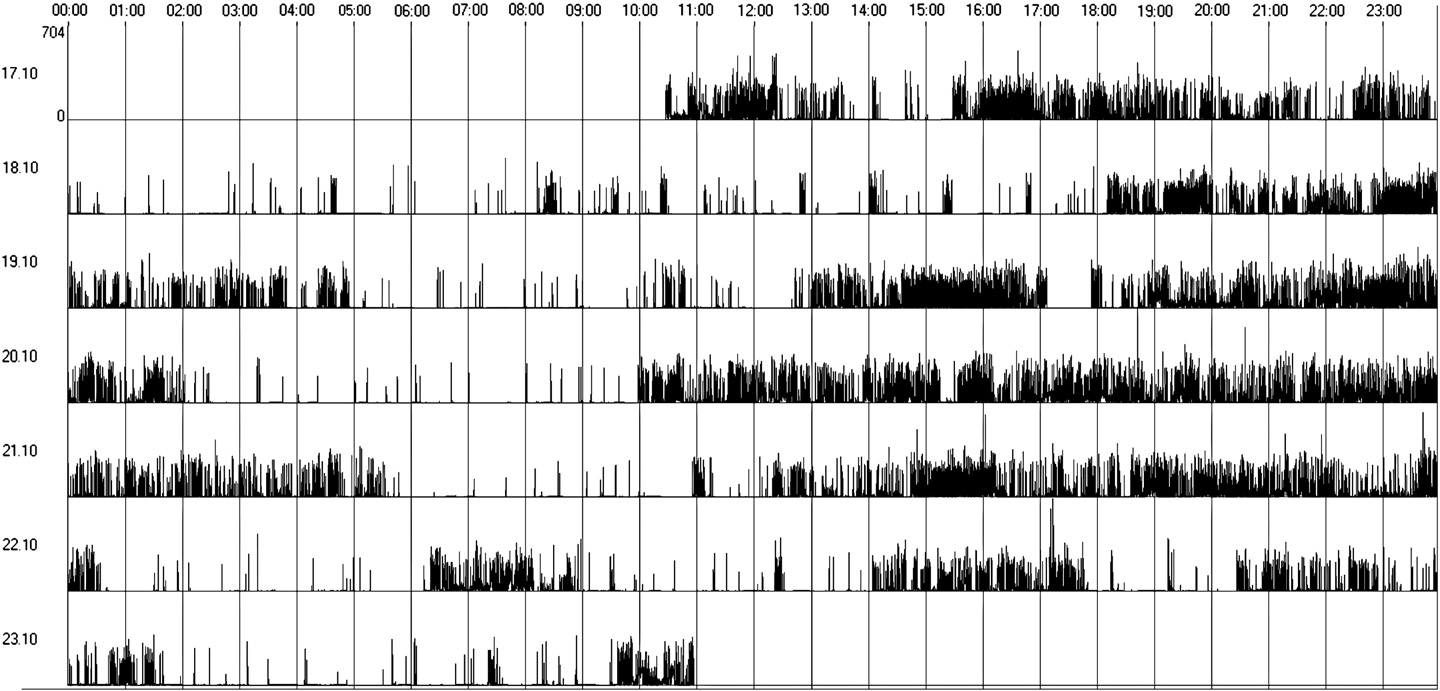

Fig. 2. Irregular sleep–wake rhythm (actogram obtained by actigraphy over a 7-day period).

asleep, and thereby having a negative impact on both sleep quality and

fetal organs such as the brain and pineal gland (Richardson-Andrews,

2009). Moreover, lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus have been

Evidence shows that when circadian rhythm sleep is disturbed,

postulated to play an important role in the aetiology of SZ (Trbovic,

daytime sleepiness, insomnia, and displacement of social timetables

2010). Therefore, future studies should explore the relation between

occur (APA, 2000). This contributes negatively to rehabilitation

sleep–wake cycles and melatonin levels in SZ patients.

interventions. Interestingly, we found an association between having

The inclusion of patients who were taking benzodiazepines before

a daily occupation, and better sleep quality and lower sleep latency,

18h00 is a study limitation, since activity levels are significantly

indicating that social and professional rehabilitation could reflect

reduced following an acute administration of lorazepam 2.5 mg

positively in the patients' circadian rhythms.

(Dawson et al., 2008). Despite that, in our sample all the 4 patients

Unexpectedly, we found no significant correlations between

had been taking diazepam (medium dose=8 mg) for long-term. Our

psychopathology, self-reported QoL and quality of sleep, and sleep/

patients presented elevated symptom levels, and therefore our results

wake variables registered by actigraphy, possibly due to the small

may not be applicable to patients in remission.

sample size. Also, our sample consisted of rather symptomatic patients,

Previous studies reported lower quantitative motor activity

possibly with low insight into their quality of sleep and QoL.

parameters than those of the present study (Walther et al., 2009;

Atypical antipsychotics tend to improve sleep induction and/or

Farrow et al., 2005; Farrow et al., 2006). This can probably be explained

sleep maintenance in SZ patients (Monti and Monti, 2004), and most

by differences in algorithms used for calculation of activity and by

atypical antipsychotics demonstrate an increase in total sleep time

differences between the actigraphs, since they have different sensor

and/or sleep efficiency in SZ patients, with the exception of risperidone

types, sampling rates and storage rates. Furthermore, the American

(Cohrs, 2008). To disentangle the effects of schizophrenia itself

Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) referred some problems when

from the influence of medication on sleep is difficult (Cohrs, 2008),

comparing actigraphy data. According to the "AASM Standards and

but it seems unlikely that treatment only could explain the differences

Practice", additional research is needed which compares results from

between the groups.

different actigraphy devices and the variety of algorithms used to

The causes for the present findings remain unknown. The tendency

evaluate actigraphy data in order to further establish standards of

for more daytime inactivity sleepiness periods in Group 2 patients

actigraphy technology (Morgenthaler et al., 2007).

may be explained by social withdrawal, reclusive behavior, and

Quantitative motor activity parameters during wakefulness were

low motor activity levels associated with the negative syndrome

related to the clinically assessed negative syndrome in schizophrenia

(Walther et al., 2009). On the other hand, positive symptoms, namely

(Walther et al., 2009). In our study we didn't replicate these findings,

suspiciousness, hallucinations and hyperactivity, could make it harder

probably because of the small sample size. Furthermore, we didn't

for the patients to fall asleep, due to an increased neurophysiologic

find a relation between motor activity parameters and sleep–wake

arousal, explaining the longer sleep latency, and lower total sleep time

rhythm. This could be explained by the fact that schizophrenia

found in this group.

is a heterogeneous disease with significant differences in activity or

Another good candidate to explain changes in the sleep–wake

immobility periods. Therefore, the volume of specific executive brain

rhythm is melatonin, a hormone produced by the pineal gland, and an

structures may affect motor behaviors. Cumulative motor activity

endogenous synchronizer of circadian rhythms. Nocturnal plasma

over a 20 h period was correlated with the volume of left anterior

melatonin levels have been reported to be reduced in SZ patients as

cingulate cortex in schizophrenia patients (Farrow et al., 2005).

compared with normal controls (Shamir et al., 2000; Viganò et al., 2001;

Finally, our results are preliminary and due to the small sample

Mann et al., 2006; Suresh Kumar et al., 2007), probably due to changes

size, and lack of a control group, need further replication.

of the pineal gland (Sandyk et al., 1990). Some theories have proposed

In summary, our findings show a trend for more disrupted sleep–

that SZ is caused by a damage produced in utero, to zinc dependent

wake patterns and circadian activity rhythms in SZ patients with

Author's personal copy

P. Afonso et al. / Psychiatry Research 189 (2011) 62–66

predominant positive symptoms; these patients also self-reported

Martin, J.L., Jeste, D.V., Ancoli-Israel, S., 2005. Older schizophrenia patients have more

worse quality of sleep and worse QoL in all domains as compared to

disrupted sleep and circadian rhythms than age-matched comparison subjects.

Journal of Psychiatric Research 39, 251–259.

patients with predominant negative symptoms.

Middelkoop, H.A., van Dam, E.M., Smilde-van den Doel, D.A., Van Dijk, G., 1997. 45-hour

These circadian abnormalities may reinforce the altered sleep

continuous quintuple-site actimetry: relations between trunk and limb move-

patterns, cognitive problems, and social engagement, with a negative

ments and effects of circadian sleep–wake rhythmicity. Psychophysiology 34,199–203.

impact on rehabilitation strategies. Moreover, our results support the

Monti, J.M., Monti, D., 2004. Sleep in schizophrenia patients and the effects of

hypothesis that poor sleep may worsen QoL in SZ patients. In clinical

antipsychotic drugs. Sleep Medicine Reviews 8, 133–148.

practice, psychiatrists should give more attention to sleep complaints

Morgenthaler, T.I., Lee-Chiong, T., Alessi, C., Friedman, L., Aurora, R.N., Boehlecke, B.,

Brown, T., Chesson Jr., A.L., Kapur, V., Maganti, R., Owens, J., Pancer, J., Swick, T.J.,

in schizophrenia since that can have a negative impact in the quality

Zak, R., 2007. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep

of life of these patients.

Medicine Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadianrhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep 30,1445–1459.

Conflict of interest

Poulin, J., Daoust, A.M., Forest, G., Stip, E., Godbout, R., 2003. Sleep architecture and its

clinical correlates in first episode and neuroleptic-naive patients with schizophrenia.

The authors report no conflict of interest. Dr. Sofia Brissos is consultant for Janssen-

Schizophrenia Research 62, 147–153.

Cilag Portugal.

Poyurovsky, M., Nave, R., Epstein, R., Tzischinsky, O., Schneidman, M., Barnes, T.R.,

Weizman, A., Lavie, P., 2000. Actigraphic monitoring (actigraphy) of circadianlocomotor activity in schizophrenic patients with acute neuroleptic-induced

akathisia. European Neuropsychopharmacology 10, 171–176.

Richardson-Andrews, R.C., 2009. The sunspot theory of schizophrenia: further evidence,

The authors thank Dr. Gama Marques for his contribution in patient recruitment.

a change of mechanism, and a strategy for the elimination of the disorder. MedicalHypotheses 72, 95–98.

Ritsner, M., Kurs, R., Ponizovsky, A., Hadjez, J., 2004. Perceived quality of life in

schizophrenia: relationships to sleep quality. Quality of Life Research 13, 783–791.

Sandyk, R., Kay, S.R., Schizophrenia, Bulletin, 1990. Pineal melatonin in schizophrenia:

Albrecht, U., 2002. Regulation of mammalian circadian clock genes. Journal of Applied

a review and hypothesis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16, 653–662.

Physiology 92, 1348–1355.

Shamir, E., Laudon, M., Barak, Y., Anis, Y., Rotenberg, V., Elizur, A., Zisapel, N., 2000.

American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Melatonin improves sleep quality of patients with chronic schizophrenia. The

Disorders. Washington, DC, 4th ed. (DSM IV-TR).

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61, 373–377.

Ancoli-Israel, S., Cole, R., Alessi, C., Chambers, M., Moorcroft, W., Pollak, C.P., 2003. The

Suresh Kumar, P.N., Andrade, C., Bhakta, S.G., Singh, N.M., 2007. Melatonin in

role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep 26, 342–392.

schizophrenic outpatients with insomnia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled

Boivin, D.B., 2000. Influence of sleep–wake and circadian rhythm disturbances in

study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68, 237–241.

psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 25, 446–458.

Tandon, R., Shipley, J.E., Taylor, S., Greden, J.F., Eiser, A., DeQuardo, J., Goodson, J., 1992.

Buysse, D.J., Reynolds, C.F., Monk, T.H., Berman, S.R., Kupfer, D.J., 1989. The Pittsburgh

Electroencephalographic sleep abnormalities in schizophrenia: relationship to

Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research.

positive/negative symptoms and prior neuroleptic treatment. Archives of General

Psychiatry Research 28, 193–213.

Psychiatry 49, 185–194.

Chae, K.Y., Kripke, D.F., Poceta, J.S., Shadan, F., Jamil, S.M., Cronin, J.W., Kline, L.E., 2009.

Taylor, S.F., Tandon, R., Shipley, J.E., Eiser, A.S., 1991. Effect of neuroleptic treatment on

Evaluation of immobility time for sleep latency in actigraphy. Sleep Medicine 10,

polysomnographic measures in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 30, 904–912.

Trbovic, S.M., 2010. Schizophrenia as a possible dysfunction of the suprachiasmatic

Cohrs, S., 2008. Sleep disturbances in patients with schizophrenia: impact and effect of

nucleus. Medical Hypotheses 74, 127–131.

antipsychotics. CNS Drugs 22, 939–962.

Van Gelder, R.N., 2004. Recent insights into mammalian circadian rhythms. Sleep 27,

Dawson, J., Boyle, J., Stanley, N., Johnsen, S., Hindmarch, I., Skene, D.J., 2008.

Benzodiazepine-induced reduction in activity mirrors decrements in cognitive

Vanelle, J.M., 2009. Schizophrenia and circadian rhythms. L'Encéphale 35, 80–83.

and psychomotor performance. Human Psychopharmacology 23, 605–613.

Viganò, D., Lissoni, P., Rovelli, F., Roselli, M.G., Malugani, F., Gavazzeni, C., Conti, A.,

Donlon, P.T., Blacker, K.H., 1975. Clinical recognition of early schizophrenic decom-

Maestroni, G., 2001. A study of light/dark rhythm of melatonin in relation to cortisol

pensation. Diseases of the Nervous System 36, 323–327.

and prolactin secretion in schizophrenia. Neuro Endocrinology 22, 137–141.

Farrow, T.F., Hunter, M.D., Wilkinson, I.D., Green, R.D., Spence, S.A., 2005. Structural

W.H.O.Q.O.L. Group, 1994. The Development of the World Health Organization Quality

brain correlates of unconstrained motor activity in people with schizophrenia. The

Of Life assessment instrument (the WHOQOL). In: Orley, J., Kuyken, W. (Eds.),

British Journal of Psychiatry 187, 481–482.

Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg,

Farrow, T.F., Hunter, M.D., Haque, R., Spence, S.A., 2006. Modafinil and unconstrained

pp. 41–60.

motor activity in schizophrenia: double-blind cross-over placebo-controlled trial.

Walther, S., Koschorke, P., Horn, H., Strik, W., 2009. Objectively measured motor activity

The British Journal of Psychiatry 189, 461–462.

in schizophrenia challenges the validity of expert ratings. Psychiatry Research 169,

Haug, H.J., Wirz-Justice, A., Rössler, W., 2000. Actigraphy to measure day structure as a

therapeutic variable in the treatment of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatrica

Wirz-Justice, A., Haug, H.J., Cajochen, C., 2001. Disturbed circadian rest-activity cycles in

Scandinavica 407, 91–95.

schizophrenic patients: an effect of drugs? Schizophrenia Bulletin 27, 497–502.

Hofstetter, J.R., Lysaker, P.H., Mayeda, A.R., 2005. Quality of sleep in patients with

Wulff, K., Joyce, E., Middleton, B., Dijk, D.J., Foster, R.G., 2006. The suitability of

schizophrenia is associated with quality of life and coping. BMC Psychiatry 3, 5–13.

actigraphy, diary data, and urinary melatonin profiles for quantitative assessment

Kay, S.R., Opler, L.A., Lindenmayer, J.P., 1989. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

of sleep disturbances in schizophrenia: a case report. Chronobiology International

(PANSS): rationale and standardization. The British Journal of Psychiatry 7, 59–67.

23, 485–495.

Keshavan, M.S., Reynolds, C.F., Kupfer, D.J., 1990. Electroencephalographic sleep in

Xiang, Y.T., Weng, Y.Z., Leung, C.M., Tang, W.K., Lai, K.Y., Ungvari, G.S., 2009. Prevalence

schizophrenia: a critical review. Comprehensive Psychiatry 31, 34–47.

and correlates of insomnia and its impact on quality of life in Chinese schizophrenia

Keshavan, M.S., Reynolds III, C.F., Miewald, M.J., Montrose, D.M., Sweeney, J.A., Vasko Jr.,

patients. Sleep 32, 105–109.

R.C., Kupfer, D.J., 1998. Delta sleep deficits in schizophrenia: evidence from

Yamadera, H., Takahashi, K., Okawa, M., 1996. A multicenter study of sleep–wake

automated analyses of sleep data. Archives of General Psychiatry 55, 443–448.

rhythm disorders: clinical features of sleep–wake rhythm disorders. Psychiatry and

Kupfer, D.J., Wyatt, R.J., Scott, J., Snyder, F., 1970. Sleep disturbance in acute

Clinical Neuroscience 50, 195–201.

schizophrenic patients. The American Journal of Psychiatry 126, 1213–1223.

Yang, C., Winkelman, J.W., 2006. Clinical significance of sleep EEG abnormalities in

Mann, K., Rossbach, W., Müller, M.J., Müller-Siecheneder, F., Pott, T., Linde, I., Dittmann,

chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 82, 251–260.

R.W., Hiemke, C., 2006. Nocturnal hormone profiles in patients with schizophrenia

Zarcone Jr., V.P., Benson, K.L., Berger, P.A., 1987. Abnormal rapid eye movement

treated with olanzapine. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31, 256–264.

latencies in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 44, 45–48.

Source: http://somnomedics.de/fileadmin/SOMNOmedics/Dokumente/PsychiatryReseach_Schizophrenia_Patients-Akti.pdf

& about . National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)National Institutes of HealthPublic Health Service • U.S. Department of Health and Human Services For Your Information This publication contains information about medicationsused to treat the health condition discussed in this booklet.When this booklet was printed, we included the most up-to-date (accurate) information available. Occasionally,new information on medication is released.

COMPOSANTES BIOLOGIQUES Quelques fondements de biologie moléculaire et de génie génétique intéressants pour approfondir le sujet, malgré le parti pris instructionniste qui sous-tend la présentation. Source : Centre Scientifique de la Biotechnologie/Industrie Canada http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/. Qu'est-ce qu'une cellule ? La cellule est l'unité du monde vivant et les millions de types différents d'organismes qui