Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

M sc thesis - ids bastian schnabel

The microeconomic impacts of diarrhoeal infections

on rural and suburban households in Uganda

The microeconomic impacts of diarrhoeal infections on rural

and suburban households in Uganda

by Bastian Schnabel

International Development Studies

Student No.: 5760208

Submitted in Amsterdam on the 28.01.2009 to the

Universiteit van Amsterdam

International School of Humanities and Social Sciences

Cover picture: LWI News

Abstract

Health economists, public health workers, and the World Health Organisation are becoming

increasingly concerned about the economic impact of diarrhoeal diseases and about

infectious diseases in general. The direct and indirect economic burdens caused through ill-

health by diarrhoeal diseases impact people especially at the individual and household level.

Also, the financial burdens caused by diarrhoeal infections are suspected to have a huge

impact on the socio-economic and demographic structure of a society (WHO 1996 & 2002).

But even more important, ill-health and infectious diseases often hinder and avert the

development processes of less developed countries.

This thesis will analyse how diarrhoeal infections economically impact people at the

household level in Uganda. A field study has been conducted to investigate direct and

indirect financial spending related to the infection of a household member with diarrhoeal

infections, and to find out what economic impact this situation has again on all household

members together. Data have been collected in the three South-Eastern districts Kampala,

Wakiso, and Jinja in Uganda, by applying a household survey, observations, and semi-

structured interviews with health experts.

The analysis shows that households which are impacted by ill-health through diarrhoeal

infections often suffer a large economic and financial burden, which is mainly caused by

expenses for medical treatment and special food. Disease prevention costs can also

substantially decrease the household's financial equity and stability. The study assumes that

on average, the financial burden for households suffering from diarrhoeal infections is as

high as 20% of the total direct and monthly household income, and the costs for disease

prevention alone can be as high as 10% of the household income.

Policy measures and health and sanitation interventions on the communal and

government level are urgently needed to protect especially Uganda's poor people from

further economic pressure caused mostly through preventable diarrhoeal infections. Such

interventions would also bring benefits to the Ugandan macro-economy and would therefore

support overall development.

Table of Contents

List of Figures….…………………………………………………………. 5

List of Tables……………………………………………………………………. 6

1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 7

1.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 7

1.2 The economic impact of infectious diseases……………………………. 7

1.3 Diarrhoeal infections, prevalence, and methods of treatment.…………………. 11

1.4 Disease prevention methods………………………….…………………………… 14

1.5 Uganda, its population, and the research locations………………………. 15

1.6 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………… 18

2. Sectoral and policy context………………………………………………….…. 18

2.1 Introduction…………. 18

2.2 The Ugandan health sector.………………………………………………………. 19

2.3 The Ugandan water and sanitation sector…………………………………….…… 22

2.4 NGOs and other organisations involved in health and sanitation practise…….… 24

2.5 Conclusion…………………………………………………………….…………. 25

3. Theoretical framework…….……………………………………………………. 25

3.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 25

3.2 Health economics concerning the economic impact of diseases…………………. 26

3.3 Livelihoods and risk-economics at the household level…………………………. 28

3.4 The medical poverty trap…………………………………………………………. 30

3.5 Rationale for the attention to the economic impact of diseases…………………. 31

3.6 Research question and sub-questions……………………………………………… 32

3.7 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………… 34

4. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 34

4.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 34 4.2 Epistemology………………………………………………………………. 35 4.3 Conceptual scheme………………………………………………………………. 36 4.4 Definition and operationalisation of concepts……………………………………. 37 4.5 Target population…………………………………………………………………. 41

4.6 Selection of sample size………………………………………………….…. 42

4.7 Sampling methods, variables, and indicators……………………………………. 46

4.8 Data processing and analysis……………………………………………………. 50

4.9 Ethical considerations……………………………………………………. 51

4.10 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………… 52

5. Analysis of locations, households, and of sanitation standards………….…… 53

5.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 53

5.2 Household livelihoods……………………………………………………………. 53

5.3 Living conditions and access to health and sanitation facilities…………………. 55

5.4 Comparison of samples……………………………………………………………. 59

5.5 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………… 60

6. Analysis of the prevalence of disease and ill-health……….…………………. 61

6.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………….……. 61

6.2 Disease prevalence and rate of infection…………………………………….……. 61

6.3 Comparison of samples……………………………………………………………. 63

6.4 Conclusion……………………………………………………………….………. 64

7. Health seeking behaviour………………………………………………. 65

7.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…. 65

7.2 Analysis of the health seeking behaviour………………….……………………. 65

7.3 Chi-square test, regression and scatter plot analysis………………………………. 69

7.4 Special food………………………………………………………………………. 71

7.5 Disease prevention methods……………………………………………….……… 72

7.6 Chi-square test, regression and scatter-plot analysis……………………………… 74

7.7 Comparison of samples and conclusion….………………………………………. 76

8. Economic burden of diarrhoeal infections on households………………….…. 78

8.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 78

8.2 Analysis of the financial impact.…………………………………………………. 78

8.3 Chi-square test, regression and scatter-plot analysis………………………….…. 81

8.4 Comparison of samples and conclusion…………………………………………… 83

9. Risk-economics and coping strategies at the household level……………….… 84

9.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…. 84

9.2 Analysis of risk-economics and coping strategies………………………….……. 85

9.3 Discussion and conclusion………………………………………………….……. 87

10. Discussion and Conclusion……………………………………………. 88

10.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…. 88

10.2 Study limitations…………………………………………………………….…… 88

10.3 Discussion and conclusion of assumptions made…………………………………. 90

10.4 Recommendations………………………………………….……………………… 93

Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….… 95

References………………………………………………………………………. 96

List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………….……. 101

Appendices………………………………………………………………….…. 103

Household questionnaire………………………………………………….……… 103

List of Figures

Figure 1.1 Salmonella typhi…………………………………………………………….…12

Figure 1.2 Vibrio cholerae……………………………………………………………. 12

Figure 1.3 Map of reported cholera outbreaks in 2005……………………………….……13

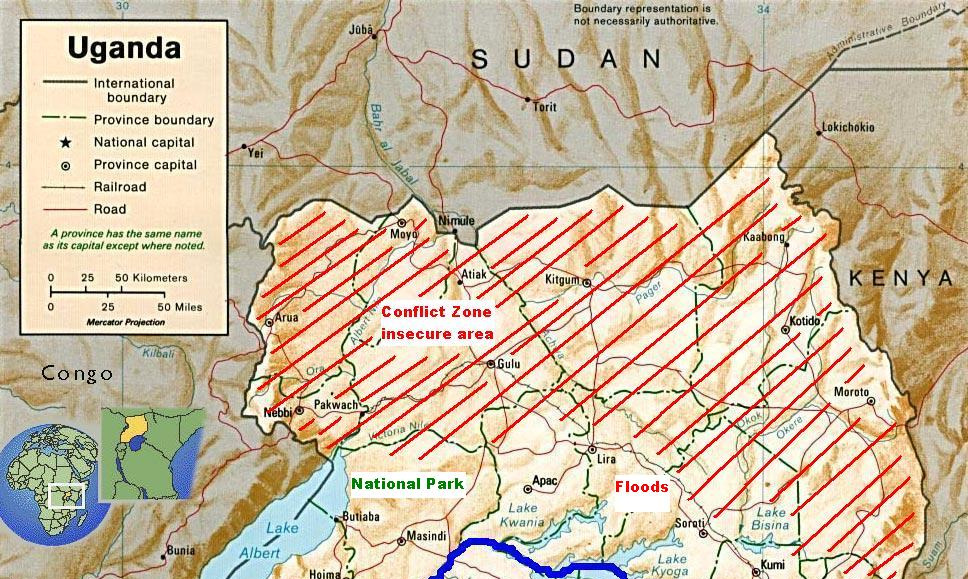

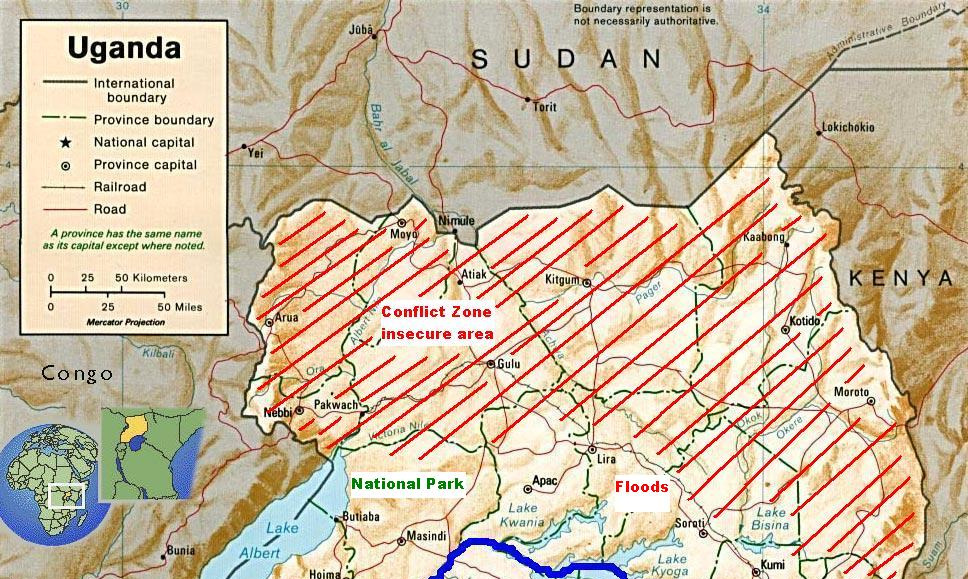

Figure 1.4 Map of Uganda with marked research area……………………………….…. 16

Figure 4.1 Conceptual framework for analysing the economic impact of

infectious diseases……………………………………………………….…… 36

Figure 4.2 Locations of research areas within Uganda……………………………….…. 43

Figure 7.1 Scatterplot of medical treatment costs vs. household income. 71

Figure 7.2 Scatterplot of disease prevention costs vs. household income…………….…. 76

Figure 8.1 Scatterplot of total disease related costs vs. household income……………. 83

List of Tables

Table 4.1 Sample size per study location……………………………………………….… 45

Table 5.1 Household structures by location……….……………………………………. 55

Table 5.2 Mode of occupation, and of water source; and dimensions of housing.…….…. 56

Table 6.1 Rate of households impacted by diarrhoeal infections by location ………….… 62

Table 6.2 Rate of infection compared to No. of episodes and type of

pathogen…………………………………………………………………. 62

Table 7.1 Health care seeking behaviour…………………………………………….…… 66

Table 7.2 Pharmacy consultation only……………………………………………….…… 66

Table 7.3 Time, transport, and company…………………………………………….……. 67

Table 7.4 Medical treatment costs………………………………………………….……. 68

Table 7.5 Association between medical treatment costs and

household income………………………………………………………. 69

Table 7.6 Correlation between medical treatment costs and

household income……………………………………………………. 70

Table 7.7 Special food……………………………………………………………. 72

Table 7.8 Rate of infection versus investments in disease prevention 1. 73

Table 7.9 Rate of infection versus investments in disease prevention 2……………….… 73

Table 7.10 Association between disease prevention costs and

household income………………………………………………………….…. 74

Table 7.11 Correlation between disease prevention costs

and household income…………………………………………………….…. 75

Table 8.1 Income versus rate of infection…………………………………………….…. 79

Table 8.2 Income ratio between infected and uninfected households and

working household members…………………………………………. 79

Table 8.3 Total financial burden caused by diarrhoeal infections……………. 80

Table 8.4 Association between total disease related costs

and household income…………………………………………………. 81

Table 8.5 Correlation between disease related costs and household income. 82

Table 9.1 Range of coping strategies………………………………………………….…. 85

Table 9.2 Household coping strategies 1…………………………………………….…. 86

Table 9.3 Household coping strategies 2………………………………………….……. 86

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction

The subject of infectious diseases has increasingly gained importance among biologists,

physicians, and epidemiologists since the first pathogens have been identified in the 19th

century. Traditionally, water-born and diarrhoeal infections like e.g. cholera and typhus have

been, and are still of major importance due to their high epidemic potential to infect a very

high number of people in only a very short time. Since the end of World War Two, infections

with diarrhoeal diseases have become less an issue in the Western World, but due to various

climatic and environmental factors, and due to missing infrastructure and insufficient health

systems, they are still a common problem in the less developed world, and especially in Sub-

Saharan Africa. Even more worrying, diarrhoeal infections have become, due to their large

number of incidences, a serious threat for local economies and for the general process of

The first chapter introduces the economic impacts which infectious diseases have on

more and less developed societies, and gives also a description of disease prevention

methods, and of Uganda and its people. First of all, the main issues concerning infectious

diseases will be described in section 1.2 in order to understand the macro- and micro-

economic impacts ill-health can cause. Secondly, a brief biological introduction to the most

common gastrointestinal pathogens will be presented in section 1.3. Thirdly, as the

mitigation of diarrhoeal diseases plays an important role in reducing the burden of infectious

diseases, disease prevention methods will be explored in section 1.4. To get an impression of

Uganda and its people's living conditions, section 1.5 introduces Uganda's topographic and

demographic features. The chapter conclusions are drawn in section 1.6.

1.2 The economic impact of infectious diseases

The economic impact of infectious diseases has been studied since the major outbreaks of

plague and cholera during the middle age in Europe, and is still of major importance for

economists and public health workers today. Especially, when taken into consideration, that a

good health condition is a precondition for any kind of human development and action. Ill-

health can lead to a decrease in human productivity and therefore averts overall development,

which is especially an issue for developing nations (Schultz 1961). According to Schultz

(1961) health is a human capital which we need to protect and invest in to increase the

overall economic output. Ill-health caused by infectious diseases can have many different

economic impacts. The most important direct economic impacts threatening society are:

premature death and consequent loss of productivity, sickness and limited loss of production,

the individual's reduced resistance to other causes of disability or reduced future

productivity, the cost of detection, treatment, rehabilitation of infections, and attempts to

prevent diseases. Also, on the macroeconomic level, poor health affects the size and

composition of the population (Weisbrod 1961).

The social, demographic, and economic burdens caused by ill-health through highly

contagious diseases like for example cholera are experienced by many different regions in

the world, and are still seen, due to their severity and extent, as one of the major obstacles for

sustainable and economic development in Africa. Especially diarrhoeal infections account for

a huge proportion of the global disease burden and mortality, and infections occur

predominantly in tropical regions like Sub-Saharan Africa where there are no or often only

insufficient sanitation facilities available. Moreover, water is increasingly becoming a

dramatic issue on the African continent, as insufficient or contaminated water sources are the

major cause of diarrhoeal infections, respectively, of high child mortality rates (WHO 1996).

For example, in 1998, 308,000 people died of war in Africa, but more than two million died

because of diarrhoeal diseases (WATSAN 2008).

Uganda, located in Eastern Africa in the Great Lakes Region between Lake Victoria

and Lake Albert is one of the hotspots with regard to the prevalence of infectious diseases

causing diarrhoeal symptoms. Due to Uganda's topography, its hot and wet tropical climate,

the prevalence of a wide range of different disease transmitting vectors, and the scarcity of

clean water and sanitation measures, diarrhoeal diseases impact the life of Uganda's

population at all levels, but especially of rural and poor people, and there is suspicion that

this situation might impact Uganda's micro and macro economy and its process of

development (Lucas et al. 1999). According to the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey

2006, malaria and diarrhoeal diseases are the major infectious diseases, impacting the whole

country and especially the western and northern districts; 26% of all children under the age

of five years are, on average, infected with some kind of diarrhoea causing infection (Uganda

Bureau of Statistics 2006). Uganda is also on a regular basis affected by cholera and dysentery

epidemics, and has a high rate of infection with giardiasis, typhoid fever, and hook worms

which further contribute to the overall burden of diarrhoeal diseases.

Various studies in Africa have therefore analysed the different impacts of such

infectious diseases on their victims and their environments, and proved, that infectious

diseases are responsible for a wide range of social and micro- and macroeconomic impacts

on the population (Weisbrod 1961 & 1973; Russell 2004; McIntyre et al. 2006). The

consequences of diarrhoeal diseases are especially a threat for economic growth and

development, and its impacts can be observed on the micro- and macroeconomic level.

Various economic assessments and impact studies from Sub-Saharan African countries with

similar conditions like in Uganda have already outlined some important economic impacts

like e.g. the costs of medical treatment and medication, transport costs to the hospital/doctor,

as well as the loss of household assets at the microeconomic level; and e.g. disease

prevention costs, and the detraction and loss of the labour force at the macroeconomic level

(Russell 2004; WHO 2002). For example, the African Medical and Research Foundation

(AMREF) recons that distance and cost play a major part in Uganda's health crisis, as about

13% of Uganda's people do not seek medical attention because they cannot afford it or

because they cannot reach a health facility. Though, today 72% of the Ugandan population

lives within 5km of a health facility, as compared to 49% five years ago (AMREF 2008).

However, the direct and indirect microeconomic impacts of diseases and ill-health are

different in every country, and due to the lack of sufficient data, there is still a lack in

understanding the relations between disease and economics, and the effects on individuals.

One can already indicate that such economic impacts caused by infectious diseases will

contribute to further poverty, with regard to Whitehead's et al. (2001) medical poverty trap,

which argues that ill-health may lead to more poverty and poverty lead to more ill-health.

Prescott (1999) highlights that a cost burden higher than 10% of the household income is

likely to be catastrophic and it can lead households into poverty. Furthermore, the importance

of analysing economic impacts of diseases is often underestimated, even if such data is

essential for cost-effectiveness analysis in the health and sanitation sector, and for justifying

further pharmaceutical research, and disease prevention methods (Hutton et al. 2004).

In less developed countries (LDCs), diarrhoeal infections are the major killers. For

example in 1998, 2.2 million people died because of diarrhoeal diseases, and most of them

were children under five years of age; and the number of cholera incidents increased in 2006

by 79% (236,896 officially reported cases) (WHO, 2007).

In Uganda, the percentage of diarrhoeal infections in urban areas increased from 2.2% in

2003 to 7.3% of the population in 2006. In the same time, the percentage of diarrhoeal

infections in rural areas increased from 4.4% to 9.8% of the population. In the northern

districts of Uganda, the percentage of diarrhoeal infections reaches as high as 13.8% of the

overall population (Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2006).

Sub-Saharan African has the highest number of diarrhoea and cholera cases, and

cholera has become an important public health issue in western Kenya and Uganda, and may

become an endemic pathogen in this region (Shapiro et al. 1999).

Due to the increasing dissemination and prevalence of diarrhoeal diseases, the social

and economic development of many LDCs, and their prospects of a better future, is being

threatened by the burden of such diseases. For example, the increasing emergence of cholera

has been noted in parallel with the increasing amount of poor and vulnerable populations

living in unsanitary conditions. Therefore, the World Health Organisation (2007) points out,

that diarrhoeal diseases such as cholera remain a threat to public health in LDCs and are used

therefore as a key indicator of social development. Furthermore, diseases can have dramatic

economic impacts at the micro and macro level, and ill-health is increasingly associated with

households being impoverished (DFID 2000). Concern about the relation of diseases, ill-

health, and economic loss has placed health at the centre of development and poverty

reduction strategies (Russell 2004).

The same argument was also put forward by Weisbrod who did some very interesting

and relevant research in North America and the Caribbean concerning the economic impact

of diseases and ill-health, and his studies (1961 &1973) clearly proved, that ill-health has an

enormous impact on the micro and macro economy, particularly in less developed countries.

For example, after the successful eradication of hookworm infections, which mainly cause

diarrhoea, in the American South in the early 1920s, the school enrolment and attendance

rates, and the rate of alphabetisation increased and therefore contributed to the

macroeconomic development (Bleakley 2007). In contrast, there is sufficient evidence that the

parasitic disease schistosomiasis, which causes diarrhoea and which is endemic in most

tropical countries, is responsible for a decline in the overall productivity of the population

impacted. The disease doesn't kill its host, but weakens its physical abilities and therefore

slows down its productivity (Sorkin 1976). Similar effects have been also observed among

populations highly impacted by malaria, which also became less productive. Such situations

will have an impact on the personal and household level as well as on the macroeconomic

level (Sachs et al. 2002; Sorkin 1976). On the microeconomic or household level, incidents of

disease infections often have a huge impact on people's and household's incomes and

savings, as costs for e.g. medical treatment, rehabilitation, and disease prevention can lead to

a financial ruin. Generally, economists must distinguish between direct and indirect

economic impacts, like e.g. the direct loss of household finances, or the indirect loss of

household productive labour, however, both scenarios will have a major economic impact on

the household level (Russell 2004).

Therefore, it's the aim of this thesis to further contribute to the understanding of the

microeconomic impacts of infectious diseases causing diarrhoeal and gastroenterological

symptoms, respectively, to find out how diarrhoeal infections directly and indirectly impact

individuals in Uganda at the household level.

1.3 Diarrhoeal infections, prevalence, and methods of treatment

To fully understand the relationship between economics and ill-health, one should have a

closer look at the definition and concepts of ill-health and diarrhoeal infections, respectively,

how they impact individuals in physiological terms.

Diarrhoea and dysentery are not diseases themselves; they are symptoms of many

diseases and mostly of gastroenterological and gastrointestinal infections. Infectious diseases

causing diarrhoea are on average the most dangerous illnesses, and they kill over two million

people every year, mostly children under the age of five years. There are approximately four

billion cases of diarrhoea world wide each year, which can be caused by a variety of more

than 100 different pathogens including bacteria (e.g. cholera), protozoa (e.g. schistosomiasis)

and viruses (e.g. rotavirus) (WaterAid UK 2007). Pathogens causing diarrhoeal infections are

spread through contaminated food (food-borne disease) or drinking-water (water-borne

disease), through unsanitary disposal of human waste, or from person to person as a result of

poor hygiene (WaterAid UK 2007). Though, many infectious and non-infectious diseases can

cause symptoms of diarrhoea like e.g. malaria or cancer, this study tried to concentrate on

victims and patients affected by the major water-borne and water-related pathogens causing

diarrhoea. These are, according to the WHO, Ancylostoma duodenale, Camplyobacteriosis,

Cryptosporidium, Entamoeba histolica, Escherichia coli, Giardiasis intestinalis, Norovirus

(virus type: Caliciviridae), Salmonella typhi and bacteria, Shingella enteritis, Rotavirus

(virus type: Reoviridae), and Vibrio cholerae. However, because no diagnostic laboratory

tests have been conducted, the researcher can not exclude the possibility that this study

included victims suffering from diarrhoea which has been caused by a disease not related to

the above described criteria.

According to a survey conducted by the Ugandan Bureau of Statistics (2006), are the

percentages of households in urban and sub-urban areas, which have been impacted by at

least one case of diarrhoea two weeks prior the survey, with on average 19.7% much lower

compared to 26.5% in rural areas.

Generally, diarrhoeal infections cause fast depletion of water and sodium in the

victim's body, and if these are not replaced quickly, the victim becomes dehydrated and its

salt and physiological balance becomes severely damaged. If more than 10% of the body's

water is lost, the victim dies. Children, old people, and people who are malnourished or

already weak are most vulnerable to such symptoms, and become even weaker and more

malnourished. The three diseases responsible for most diarrhoea related death are bacillary

dysentery, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella typhi (see Figure 1.1 and 1.2), and these

pathogens are highly endemic in Africa's Great Lakes Region.

Bacillary dysentery is more dangerous compared to amoebic dysentery, and it is

estimated that 140 million people get infected with this bacteria each year, and more than

300,000 victims don't survive this infection, mainly children below the age of five years

(WaterAid 2007). One of the areas with the highest prevalence is Sub-Saharan Africa.

Bacillary dysentery is caused by the bacterium Shingella enteritis, which is transmitted via

contaminated water, food, and arthropods (e.g. flies), and which then infects the intestines.

Figure 1.1 Salmonella typhi Figure 1.2 Vibrio cholerae

(Source: WHO 2008)

The major symptom is severe watery and bloody diarrhoea. Treatment is usually based on an

oral rehydration salt solution, high intake of fluids, and in some cases on antibiotics such as

e.g. Ciproflax® (WHO 2008).

The highly infectious disease cholera, which is caused by the bacterium Vibrio

cholerae, is often described as the classic water-borne and diarrhoea causing disease (Sack et

al. 2004). The pathogen is mainly transmitted via contaminated water and food, and is

endemic in most tropical and sub-tropical regions. Originally, the pathogen was only

endemic in the Indo-Bengal region, but it spread in the 18th century all over the world and

caused severe pandemics and left thousands of people death. Similar to Shingella enteritis,

cholera kills mainly children between the age of two and four years, as well as old people,

and people suffering from malnutrition. In 2000, 118,932 cases of cholera were reported in

Africa, and officially 4,690 people died. The number of unreported cases was probably much

higher (Naldoo et al. 2002). Major symptoms are severe watery diarrhoea (adults can lose

more than 14 litres of body fluids a day) and vomiting. Treatment is based on the concept of

replacing fluids as fast as they are being lost, followed by the intake of oral rehydration

solution (ORS) or an intravenous polyelectrolyte solution. Antibiotics can shorten the time of

recovery, but should only be used in limited cases as they increase the risk of the

development of resistant bacteria (Sack et al. 2004). The prevalence of cholera (in 2005) can

be seen in the epidemiological map below (Figure 1.3).

Another very common diarrhoea causing disease in Africa is typhoid fever, which is

caused by the bacteria Salmonella typhi. It is estimated that typhoid fever infects

approximately 17 million people per year, and about 600,000 infected people die each year

(WaterAid 2007). Almost all typhoid cases occur in less developed countries as the pathogen

is virtually eliminated in the developed world through sanitation facilities and vaccines. The

disease causes high fever, diarrhoea, and in some cases even intestinal haemorrhaging or

perforation. In contrast to cholera infections, victims infected with typhoid are often long-

term carriers who spread the pathogen over a long time period (Sack et al. 2004). A vaccine

against typhoid is available, but doesn't provide full protection against infection. Typhoid

fever is mainly treated with antibiotics (WHO 2008).

Figure 1.3 Map of reported cholera outbreaks in 2005 (Source: GISed 2008)

However, the most common infection causing symptoms of diarrhoea in tropical

regions and especially in Africa is an infection with hookworms. It is estimated that about

740 million infections occur through this protozoa in the world's tropical and sub-tropical

regions each year (Hotez et al. 2004). In Sub-Saharan Africa the disease (which often becomes

chronic) is mostly caused by the hookworm Ancylostoma duodenale, which penetrates the

skin or mucous membranes from contaminated soil, water, or food items. The worm then

lives in the small intestines and causes major blood losses into it, which often results in

anaemia, especially in people whose dietary iron level is already low (Feachem et al. 1986).

Children are very vulnerable to this disease as an infection with hookworms can damage their

growth and symptoms can become chronic. The disease can be treated with a single dose of

albendazole, mebendazole, levamisole, or pyrantel, which is the standard treatment for all

infections caused by soil-transmitted helminths (WHO 2002).

1.4 Disease prevention methods

Appropriate and fast treatment is very efficient in reducing the mortality from diarrhoeal

infections, however, this can not reduce the agents responsible for the infection nor does it

decrease the incidents of diarrhoea. The prevention of infectious diseases is one of the key

factors to reduce the human and economic burden caused by the disease. Prevention of

diarrhoea primarily means to protect susceptible people most at risk (these are children, old

people, and people who are already ill or weak) from acquiring diarrhoea causing diseases.

Adequate food, safe water, and personal hygiene are the key words for proper diarrhoea

prevention techniques (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2005).

The WHO (1990) has given priority to the following strategies and interventions for the

prevention of diarrhoeal infections:

First, the promotion of exclusive breast feeding during the first 4 to 6 months of life, because

immunological properties in the breast milk help to protect infants from infection and breast

milk is generally clean.

Second, improved weaning practise, this requires the selection of nutritious food for children

over 4 to 6 months old, and good hygienic education and practice such as e.g. washing hands

before and during food preparation.

Third, the risk of getting infected with a disease causing diarrhoea can be significantly

reduced by using exclusively clean and disinfected water. Prevention of the contamination of

stored water at the household level is therefore important to decrease the transmission of

diarrhoeagenic pathogens. The preferred methods are boiling water or chemical treatment.

Fourth, personal hygiene like proper hand washing with soap and water before preparing

food, before feeding children, and during ablution reduces diarrhoeal infections. House and

kitchen hygiene is also important for the prevention of diarrhoea related diseases.

Fifth, constant access and use of clean, functioning latrines and proper disposal of faeces of

both humans and animals are essential in preventing the spread of pathogens causing

diarrhoea. And last, immunisation against measles reduces the incidents of measles related

diarrhoeal symptoms (WHO 1990). There are also vaccines widely available against the

infections with typhoid, cholera, rotavirus, and Shigella, though they are expensive and still

lack full effectiveness. These prevention measures are especially important during post flood

or post cyclone situations. Also, the supply of safe drinking water and the vaccination of

children against measles are always the first steps to be taken (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2005).

For example, the Water and Sanitation Resource Centre in Uganda (WATSAN) recons that

the simple act of washing hands with soap and water can reduce diarrhoeal infections by one-

third (WATSAN 2008). Furthermore, health officials, local communities, and households must

be actively involved in the process of planning and implementing water resource projects. If

local people have power over their own water sources, they are more likely to protect them

(Hunter et al. 1993).

1.5 Uganda, its population, and the research locations

The field research and data collection for this study took place in Uganda, which is located in

East Africa in the Great Lakes Region between Kenya and the Democratic Republic of

Congo. The topography of the country is defined by tropical bushland, tropical rain forest,

and tropical mountain forest, and the meteorology is strongly influenced by two rain seasons

(from March until June and from September until November). The climate in Uganda during

the field research period was wet and hot and very humid with temperatures between 20˚C

and 35˚C and a high rate of rainfall due to the impact of the main rain season lasting from

March until June.

The Republic of Uganda gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1962, and

is currently governed by the democratically elected President Lt. Gen. Yoweri Museveni who

has held on to power since 1986. Uganda is also, together with Kenya and Tanzania, part of

the East African Community (EAC). The country has 29 million inhabitants, with about 85%

of the population living in rural areas, and with 1.9 million people living in the capital

Kampala. The official language is English, but tribal languages like Luganda, Luo, Iteso

Rwanyankole, and Swahili are also widely used. The Baganda are with 16.9% of the

population the largest ethnic group in Uganda followed by the Banyakole with 9.5% and the

Basoga with 8.4% (CIA factbook 2008). The major minorities in Uganda are international and

internally displaced people (refugees) who in the main have migrated from war suffering

neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and South Sudan.

But also from Northern Uganda, where a rebel group called the Lord's Resistance Army

abducted more than 20.000 children and displaced more than one million people (Human

Rights Watch 2008).

These internally displaced persons (IDPs) live in hundreds of IDP-camps all scattered across

Northern and Central Uganda.

Despite some unrest in Uganda's north and along the borders, the economy is growing

and the national monthly average income per person and capita for all districts in Uganda is

about $90, though a high proportion of the salaries are earned through the informal business

sector. The national alphabetisation rate is 67%, but school attendance in urban and suburban

areas is generally higher than in rural areas (CIA factbook 2008).

The study locations for suburban interviews were located in and near the Ugandan

capital Kampala, and for rural interviews they were located in the surrounding districts

Wakiso and Jinja in the South-Eastern part of the country.

Figure 1.4 Map of Uganda with marked research area

The few urban areas in Uganda often still impart a rural expression compared to other

East African cities. Thanks to the equatorial climate and the high fertility of the soil, there are

plants and crops growing everywhere in urban places, even next to major roads in the city

centres. Apart from the commercial and traffic impacted city centres and from the nice and

green expatriate settlements, the majority of the poor urban and suburban population lives in

suburbs and slums scattered around the city centres. The target population for this study are

people who live in such slums mainly around Kampala and in rural communities in

neighbouring districts. The main forms of people's livelihoods located in slums are based on

small-scale businesses, on wage and day labouring, and on begging. Livelihoods are mostly

structured very simply and usually concentrated only on gaining basic needs for survival.

During the rainy seasons, these slums are often impacted by floods, and often the slums lack

the most basic infrastructure like paved roads, adequate housing, electricity, or piped fresh

water and sanitation facilities.

Rural areas in South-East Uganda like the districts Wakiso and Jinja are shaped mostly

by tropical bushland as well as by large tea, banana, and cane sugar plantations. The villages

and their fertile fields lie between forests and wetlands as the districts Wakiso and Jinja are

located next to Lake Victoria. Jinja district is also shaped by the magnificent source of the

Victoria Nile River, which crosses the whole district from south to north.

The livelihoods of households located in rural places were predominantly shaped by

subsistence farming and by wage labouring through the commercial farming sector. Though,

most forms of livelihoods in rural places were as simple and basic as in the suburban slums,

most households were at least self-sufficient due to subsistence farming.

The shape and the level of infrastructure in villages depend usually on the region in Uganda,

on its topography, and on its accessibility. Some rural communities, especially the ones near

the capital Kampala, even have access to electricity and to tap water, while people in more

remote rural communities still live very traditional without any infrastructure. With regards

to water supply and sanitation, the access to a clean water sources in Uganda has increased

from 44% in 1990 to 60% in 2004. During the same timeframe, sanitation coverage has also

increased considerably. However, water and sanitation coverage in rural areas, where 88% of

the population lives, is lower than in urban areas (WHO & UNICEF 2006). In urban areas,

fresh water is usually supplied by the National Water and Sewage Corporation (NWSC), a

public corporation working on a commercial basis. In contrast, in rural areas, the local and

district governments are responsible for adequate water supply and sanitation coverage

Additionally, every slum and every village, or a part of it, is controlled and

administered by a chief or community leader who manages local concerns, and most

business, development, and research related activities must be first approved by him. The

chief or community leader usually belongs to the main ethnic group dominating in the region

and is very respected by all community members.

1.6 Conclusion

This chapter introduced and outlined the severe macro- and micro-economic impacts which

diarrhoeal disease can have on societies, by giving at the same time an insight into the

biological part of this subject. Major micro-economic impacts caused through ill-health have

been identified as premature death and the consequent loss of productivity, sickness and the

limited loss of production, the individuals reduced resistance to other causes of disability, the

costs of detection, treatment, rehabilitation, and of attempts to prevent ill-health. The

researcher briefly introduced the most common gastrointestinal pathogens like e.g. cholera

and typhus, and also highlighted how infections with them can be prevented. The sub-chapter

about disease prevention showed, that it is not too late nor is it impossible to reduce the

burden of infections, preconditioned people and governments show concern and provide the

needed finances to condemn this global problem. As the study took place in Uganda, we have

also briefly learned about its topography and its demography to get an impression about local

conditions and setting.

2. Sectoral and policy context

2.1 Introduction

The present chapter presents and outlines the sectoral and policy context in which this study

took place. First of all, a summary of the different agents and sectors which are involved in

the prevention and treatment of ill-health and diarrhoeal infections will be given in section

2.2 in order to understand the complexity of Uganda's health system and its connections and

dependencies to related sectors. Secondly, as the level of sanitation plays an important role in

people being at risk to diarrhoeal infections and to ill-health, the water and sanitation sector

and its related policies will be explained and discussed in section 2.3. Thirdly, in section 2.4,

NGOs and other organisations involved in health and sanitation practise, respectively their

roles and activities will be described. The chapter conclusions are drawn in section 2.5.

2.2 The Ugandan health sector

According to Uganda's Health Sector Strategic Plan 2, which main purpose it is to guide and

to manage the national health sector, there are a number of different sectors and agents

directly and indirectly involved in the health prevention, delivery, and policy process. Apart

from the Ministry of Health, following government sectors are counted to the health related

sector and are also actively involved in fighting diarrhoeal infections:

1. Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development

• Mobilisation of resources 2. Ministry of Lands, Water and Environment

• Mapping availability water sources for all health facilities • Development of water sources • Provision of sanitary services 3. Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development

• Mainstreaming gender in plans and activities of all sectors including the engendering of the budget • Development of policies for social protection of the vulnerable groups 4. Ministry of Works, Housing and Communication

• Construction and maintenance of roads for accessing health facilities to facilitate patients flow and referral of patients 5. Ministry of Education

• Interpreting information for promoting and adopting healthy lifestyles • Incorporating public health training into the curricula of schools at all levels • Training of health workers • Research and development 6. Ministry of Local and District Governments

• Recruitment and deployment of appropriate trained staff health workers by District Service Commissions • Delivery of health services • Supervision and monitoring of health service delivery

(Uganda Ministry of Health 2005) As outlined above, Uganda's national health system is shaped by different sectors and agents,

and consists of public health facilities including the health services of the army, police, and

prisons, and of private health delivery systems. However, most institutions directly involved

in health delivery are controlled and managed by the Ministry of Health, and as it is beyond

the scope of this study to consider all agents involved, the health sector itself will be in main

focus in this sub-section.

The private health sector is divided between private-not-for-profit organisations (PNFP)

including missionary health centres, private health practitioners (PHP), and between the

traditional and complementary medicine practitioners (TCMP). Some communities also

provide private health services (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). Public health facilities are

divided into different levels. They are structured in national level institutions, national

referral hospitals, regional referral hospitals, district health services, and in sub-district health

services like local health centres and village health teams. In contrast to private health

services, medical services provided by the public health facilities are now generally free of

charge, even if Christiaensen et al. (2005) argue that payment for both public and private

health facilities has in practise long been the norm in Uganda (Christiaensen et al. 2005).

However, according to interviews, there are a lot of public health facilities short on adequate

medication and on medical equipment, and patients are often forced to buy the prescribed

medication by themselves through the private health market. Furthermore, according to

Christiaensen et al. (2005) and to various articles published in the local press, corruption and

illicit practise as well as the employment of unqualified staff are not unseen within the public

health services.

However, the Ugandan Ministry of Health has created a public private partnership for

health to improve health services and relations between both sectors. Efforts will be directed

to strengthening and broadening the partnership through more active engagement with other

health related sectors, professional associations, private health care providers, civil society,

and representatives of the principal consumers (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). The Ugandan

Ministry of health is also concerned about the equitable access for vulnerable communities

and individuals to health services, and therefore included a policy in its Health Sector

Strategic Plan 2 to support these people (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). The public health

sector considers vulnerable individuals and high-need groups as poor people, children,

orphans, elderly people, women, displaced people, and people living in areas with insecurity.

The efforts of the Ministry for Health are particularly accomplished through increased

funding to primary health care services, the abolition of user fees, and through the targeted

use of the Primary Health Care Conditional Grant (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005).

Furthermore, due to the fact that over 75% of Uganda's disease burden is considered to

be preventable as it is primarily caused by poor personal and domestic hygiene and

inadequate sanitation practices, the Ministry of Health increasingly supports health

promotion, disease prevention strategies, and community health initiatives, and included new

policies concerning these issues in its Health Sector Strategic Plan 2. Diarrhoeal diseases,

which are suspected of diminishing productivity and increasing poverty, are on top of the list

of preventable diseases (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). Therefore, the public Mulago

Hospital in Uganda's capital Kampala has created a diarrhoea management unit, which

specialised on paediatric treatment and on epidemiological research.

With regards to the health policy frame work, Uganda has developed (together with

international partners and advisors, notably UNICEF), a compact policy frame work that

aims at the improvement of Uganda's health status and at decreasing infectious diseases.

Especially, the Health Policy Advisory Committee (HPAC) has proved beneficial in

providing overall policy guidance to the sector (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). The lead

paper of this frame work is the Health Sector Strategic Plan, which has first been introduced

in 2000 after the introduction of the newly created National Health Policy (1999). The

policies included in the plan focus on cost sharing of health services, on setting up health

management committees that include participation from local communities, and on the

abolishment of user fees. With regards to the study's focus, the policy's paragraph about the

abolishment of user fees is very interesting, as it is suspected to have a positive effect on

people who are impacted by diarrhoeal infections, because it decreases the financial burden

of patients who seek care in public health facilities. As required by the National Health

Policy (1999), the Health Sector Strategic Plan focuses as well on health promotion, on

disease prevention, and on equitable access to health services for vulnerable communities

and people (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). Following targets of the Health Sector Strategic

Plan are especially interesting with regards to the study's focus and research question:

- reduction of incidences of annual cases of epidemic diarrhoeal diseases from 3/1000

- reduction of the cholera specific case fatality rate from 2.5% to 1.0%

- increase of the proportion of patients with epidemic diarrhoea receiving appropriate

treatment within 12 hours of onset of symptoms

Subsequently, following core interventions of the Health Sector Strategic Plan are as well

very interesting with regards to the study's focus and research question:

- Diarrhoeal disease surveillance, and epidemic preparedness and response

- Prompt and appropriate case management

- Community education and mobilisation

- Reactivation of the Protocol of Cooperation of Countries in Great Lakes Region

Unfortunately, there is no national or social health insurance system in Uganda yet, but

the Ministry of Health is currently in the process of drafting the law and legal base to govern

the scheme. To provide further support for the subsidisation of medical costs, Community

based Health Insurances Schemes (CBHI) have recently been introduced. However, low

recruitment and retention rates, high management costs, and low uptake by poor people slow

down its success. Still, inadequate financing remains the major constrain inhibiting the

development of the national health sector in Uganda and the funding of health services has

dramatically declined (Lucas et al. 1999). For example, funding a basic package of services in

developing countries has been estimated at US$ 30 - $ 40 per capita, but the current level of

public funding from the Ugandan government for health services per capita is only about

US$ 8 (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005). Furthermore, the World Bank made new loans for the

support of health facilities conditional on the introduction of a national health system based

on user-charges. However, the opposite happened and user fees got abolished. Today, the

health sector and the water sector have been identified as key sectors under the 2004 Poverty

Eradication Action Plan (PEAP), Uganda's main strategy to fight poverty (Republic of Uganda

2.3 The Ugandan water and sanitation sector

The water and sanitation sector is the second most important sector (after the health sector)

for the prevention, mitigation, and control of diarrhoeal infections and therefore plays also a

vital role when it comes to the prevention of disease burdens. Uganda's water and sanitation

sector is defined by a variety of different agents (similar to the health sector) that provide the

following services: clean water for domestic use, water for agricultural use, mobilisation and

training for community management and awareness, and sanitation and hygienic services

(DANIDA 2009). To improve its effectiveness and coverage the sector was reformed through

several laws in 1995, leading to decentralisation and increased private partnership (UN-Water

2006). The lead agency for most concerns related to water and sanitation is the Ministry of

Lands, Water and Environment, respectively, its Directorate of Water Development (DWD).

It provides regulations and policies, coordination, support, capacity building, and some

implementations that cannot be handled by the local governments such as town piped water

supply. The Directorate of Water Development is supported in its role by the semi-private

National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC) that implements and manages the piped

water supply in sub-urban and urban areas (DANIDA 2009). Also, the Environmental Health

Division (EHD) controlled by the Ministry of Health is in charge of an integrated and

national sanitation strategy (Uganda Ministry of Health 2005).

Overall, Uganda has a relatively well-developed framework of national sanitation

policies. Laws and regulations have been created or revised to support these policies, a

process that is still incomplete but currently continuing. For example, the new constitution

established in 1996 states that every Ugandan has the right to a clean and healthy

environment, including drinking water (IRC 2009).

The legislative arm of the national water and sanitation policies is the Ministry of

Lands, Water and Environment, and the executive arm is the Directorate of Water

Development which also supports the local governments and other service providers (DWD

2009). The current legislative water sector framework, implemented through the 1995 Water

Statute, has the objectives to promote rational water use and management, to provide clean,

safe, and sufficient domestic water supply to all people, to develop water and its use for other

purpose like e.g. irrigation and industrial use, and to control pollution and the safe storage,

treatment, discharge, and disposal of waste that may cause water pollution or other threads to

the environment and human health (Republic of Uganda 1995). The management of the water

sector is controlled by following policies:

- The sector policy and legal framework includes the Constitution of the Republic of

- The Local Government Act (1997), Uganda Water Action Plan (1995). - The National Water Policy (1999), Water Statute (1995). - The Water Resources Regulations (1998). - The Water Supply Regulations (1999). - The Water (Waste Discharge) Regulations (1998). - The Sewerage Regulations (1999). Others include: The Environment Management

- Land Act (1998), National Health Policy and Health Sector Strategic Plan (1999). - The National Gender Policy (1997).

(DWD 2009) The National Water Policy (1999) is especially important, as it promotes the principals of

integrated water management and water supply. It also recognises the economic value of

water and supports the participation of all stakeholders in all stages of water supply and

sanitation (DWD 2009). There have also been several efforts to develop an official national

sanitation policy, the latest being the draft National Environmental Health Policy for Uganda.

These policies take into account the needs of different population groups in urban centres,

small towns, rural growth centres and rural communities, and have led to the preparation of

development approaches and technical guidelines that have been adjusted to the social and

economic conditions of the user communities (IRC 2009). Therefore, the policies stated above

together with the health policies create a well connected legal framework which should

decrease diarrhoeal infections as well as its burden, if implemented effectively.

2.4 NGOs and other organisations involved in health and sanitation practise

To some extent the essential follow-on activities and interventions are occurring primarily

through donor-funded programmes for health, water supply, and sanitation. The emphasis,

however, tends to be on sanitation and water supply projects, though funding allocations tend

to favour urban over rural areas. Sanitation is not considered to be a separate programme

area, either in funding or project development terms. Moreover, individual households,

where sanitation needs are greatest, generally receive no material support for the construction

or maintenance of latrines (IRC 2009). Promotional and technical guidance for sanitation is

available at the household level, but even these means of assistance are inadequate to meet

the need (IRC 2009). To overcome this issue several international and non-governmental

organisations are active in Uganda's health and water sectors. Out of these NGO activities

emerged the Uganda Water and Sanitation Network (UWASNET) that functions as a NGO

umbrella organisation providing coordination and capacity building support. Major

contributors and donors are the development corporations of Denmark, Sweden, Germany,

Austria, Great Britain, and the European Union. Especially DANIDA and DED/GTZ/KFW

are very active in the water and sanitation sector. As well as the NGOs African Medical and

Research Foundation (AMREF), WaterAid, the Water & Sanitation Resource Centre

(WATSAN), and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, that all have a

special focus on the prevention and treatment of diarrhoeal diseases. Major joint-

interventions are the National Sanitation Working Group, the National Sanitation Week, the

National Hand-Washing Campaign, and the Water and Sanitation Sector-Working Group

(WSSWG). All of these interventions aim at increasing the participation between the

different stakeholders, at increasing safe water supply and adequate sewage disposal, and at

preventing water-borne and water-related diseases such as diarrhoeal infections (DANIDA

2.5 Conclusion

As outlined, Uganda has developed a structured framework of policies aimed at fighting

diarrhoeal diseases and is still in the process of doing so. The information about the different

sectors and agents involved in Uganda's health, water, and sanitation sectors are an important

base for the study's economic analysis, as most costs created through ill-health are suspected

to emerge from the health sector and to a small extent from the water sector. Especially the

National Health Policy (1999) will be of advantage to the people as it aims at preventing

diarrhoeal diseases as well as its burden through the abolishment of user fees. The water and

sanitation sector also created a range of different laws aiming mostly at the safe supply of

water and at the safe discharge of sewage, which is essential for the prevention of diseases

and ill-health. Additionally, a lot of NGOs are active in this field, and sanitation interventions

seem to become more frequent and effective. However, in terms of policy, there still seems to

be a lack with regards to cost-recovery. Some patients need to consult private health facilities

if they are nearer by, or require additional treatment that cannot be provided by the public

health sector, which creates extra cost. Also, medication and drugs are not always provided

for free under the National Health Policy (1999), and there is no system to compensate for

lost productive labour time such as a national health insurance, though the Ugandan

government is aware of the issue and plans for a national insurance scheme are going ahead.

In any way, the research conducted through this study can help to further adjust the policy

framework and to give further recommendations for policy building.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1 Introduction

The present chapter further introduces the relations of infectious diseases, ill-health, and the

economy, and also highlights the health economic theories relevant for this study. First of all,

health economic literature and theories will be described in section 3.2 in order to understand

the major coherences between ill-health and the economy. Secondly, to understand how

people mitigate and cope with the burden of ill-health, household livelihoods and the

meaning of risk-economies and coping strategies will be discussed in section 3.3. Thirdly, as

poverty is a status which is suspected to be closely related to ill-health, the concept of the

medical poverty trap will be explored in section 3.4. On the basis of the reviewed literature

and of the introduced theory, the researcher's rationale for studying the micro-economic

impact of diarrhoeal infections on households will by explained. Lastly, section 3.6

highlights the study's research question and sub-questions. The chapter conclusions are

drawn in section 3.7.

3.2 Health economics concerning the economic impact of diseases

"Much present morbidity is unnecessary, much mortality premature. Better health is within

our grasp if only we choose to pay its price."

(Weisbrod 1961)

Theoretical approaches concerning the micro- and macroeconomic assessment of infectious

diseases have been applied since the first cholera epidemics in Europe during the 19th

century. And the English economist Alfred Marshall analysed already in the early 20th

century the rational and irrational motives that led individuals, families, and employers to

invest in human capitals, of which health is one of them. He used this knowledge for

analysing patterns of labour supply and household incomes and his theories still influence

health economics (Agich et al. 1986).

Knowledge and data regarding the economic impact of infectious diseases is becoming

again very important due to recent poverty reduction efforts, due to the rising demand in new

health insurance schemes in developing nations, and due to rising incidence of infectious

diseases caused by global warming. In setting priorities among control efforts across many

different types of diseases, it is essential for development and health authorities to measure

the welfare, capital, and asset loss inflicted upon a population by a given disease (Philipson,

1999). Moreover, information on the economic impact of infectious diseases is needed to

target interventions efficiently and to justify further investments in disease research,

mitigation, and control. Policy makers and planners need exact numbers and statistics of e.g.

disease incidents and their financial impacts to justify e.g. sanitary interventions (Chima et al.,

2003). Such economic health information are also of importance for cost-effectiveness

analysis e.g. in the water and sanitation or development policy sector, and as argued by the

WHO (2002), data about economic costs and effects of disease prevention and intervention

programs as well as about the economic impact of water-related diseases remain critically

important (WHO, 2002; Hutton et al., 2004). Also, microeconomic health data concerning the

extent of diseases is necessary to assess health sector reforms as e.g. the current trend of

privatisation going on most African countries (McIntyre et al., 2006). If medical expenses are

becoming less subsidised, public spending will obviously rise and private savings will

decline, making the household more vulnerable to impoverishment.

Breyer et al. (2005) argue that health is the most important precondition for economic

development, because ill-health decreases and impedes individual and commercial

productivity enormously. Therefore, it is important to analyse what kind of commodities and

assets someone is willing to trade-off in exchange for well being and good health; and also,

to analyse what kind of commodities and assets someone is willing to trade-off in exchange

for the re-establishment of a good health status in the case of ill-health (Breyer et al. 2005).

According to the Grossman model, which argues that health is an integral part of the human

capital, health and capital are both inter-connected assets and the values and optimums of

both are controlled over time by the individual. Therefore, increasing costs for health

services and products also increase the necessary level of investments in the total health

capital, respectively, decrease the total health capital. However, with the progress of the

individual aging process, the level of amortization will increase, and the investment in a good

health status becomes less profitable. Also, a good health status or the total health capital is

influenced by happenstance and is therefore not super imposable and tradable. Moreover, in

the case of less affluent individuals or households, the health status correlates negatively with

the demand of health services, as individuals impacted by ill-health can't afford the necessary

services to restore their health status (Grossman 1972).

However, for developing, infrastructure, and health authorities to be able to finance and

subsidise medical expenses, respectively to prevent them so that they cannot cause economic

impacts at the household level, they rely on data about what micro and macroeconomic

damage ill-health and diseases can cause. Without this data, economists are not able to carry

out cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses to evaluate demand for health services,

health interventions, or expenditures for health care. The cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is

an economic analysis that compares the relative expenditures and outcomes (effects) of two

or more courses of action. Cost-effectiveness analysis is often used where a full cost-benefit

analysis is inappropriate e.g. when the problem is to determine how best to comply with a

legal requirement. This analysis is also often used to analyse the "cost-effectiveness" of

health interventions, or disease prevention strategies (Murray et al. 2000). Cost-benefit

analysis (CBA) is mainly used to assess the value for money of very large private and public

sector projects like e.g. the installation of water and sanitation facilities. This is because such

projects tend to include costs and benefits that are less amenable to being expressed in

financial or monetary terms (e.g. environmental damage) (Folland et al. 2007). In health

decision making, such as in bio-medical and disease research, the cost is often replaced by

risk, and the cost-benefit analysis is turned into a risk-benefit analysis.

According to various sources, the household-level and its microeconomic relations are

the preferred unit of analysis for assessing the cost of diseases and illness, by including

indirect and direct incomes and expenditures of the targeted households (Russell, 2004). An

analysis from the microeconomic perspective is important in this study as microeconomics

focus on how individuals and households make decisions to allocate limited resources. Also,

microeconomics considers issues as how households reach decisions about consumption and

savings (The Economist 2008).

3.3 Livelihoods and risk-economics at the household level

Inadequate access to health care is a major health and development issue, which is closely

linked to people's livelihoods and their ability to generate livelihood assets such as e.g.

human or financial capital. Moreover, economic coping strategies at the household level,

respectively household risk-economics, are largely shaped by the availability and

diversification of livelihood assets (Obrist et al. 2007).

This declaration is especially true, when seen through the livelihood approach, which

emphasises people's need to a diverse mix of assets including material and social resources.

Livelihood assets include human and social capital, natural capital, physical capital, and

financial capital. And people's health seeking behaviour, e.g. whether a sick person consults

a pharmacy, a traditional healer, or a professional doctor first, depends largely on the

household's ability to access livelihood assets of the household and the wider society (Obrist

et al. 2007). Basically, people's livelihoods determine their ability to cope with economic and

health shocks. Therefore, the access to livelihood assets is a key issue for sustainable

livelihoods. However, many people have difficulty in accessing household and community

assets, which often constrains their ability to cope with diseases.

As every household needs to apply a set of coping strategies and risk-economics when

impacted by ill-health, regardless of whether it is rich or poor, the analysis of household's

risk-economics and vulnerability is a key feature of livelihoods and of the understanding of

poverty (Devereux 2001). For example, diarrhoeal diseases are a major risk factor for

households and for people's livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa, as they can result in a decline

of productivity and financial equity. And according to Christiaensen et al. (2005) infectious

diseases are one of the major determinants for household vulnerability in non-arid areas in

Eastern Africa such as in Uganda.

To mitigate such a risk, individuals or entire villages can, for example, join a

community based health insurance as part of their strategy to mitigate risk from disease

(Wiesmann et al. 2000). To protect the livelihood assets necessary for such insurances,

government and development agencies could, through public interventions, enhance

livelihood-protection functions such as e.g. fertilisers and seed subsidies (Devereux 2001).

Another form of risk-economics and of decreasing household's vulnerability is to diversify

the household income. This strategy is often preferred by households which want to

smoothen their income ex ante a household economic crisis, as the household would be very

unlikely be able to smoothen its income and consumption ex post (Christiaensen et al. 2005).

Informal insurances and self-insurance through household assets would also be an alternative

method of risk-economics as compared to private commercial insurances which are almost

nonexistent in Sub-Saharan Africa anyway. Unfortunately, most households are constrained

to adapt this strategy, probably because access to assets is often limited and asset markets are

poorly functioning during and after a crisis (Dercon 2002).

However, risk-management should be distinguished from coping strategies. According

to Dercon (2002), risk-management strategies attempt to decrease the risk upon income

processes ex ante, therefore, risk-management is income smoothing. In contrast to coping

strategies, which deal with consequences of income risk ex post and are therefore

consumption smoothing (Dercon 2002).

For example, households which cannot afford medical treatment costs because they are poor

and lack any form of insurance, are often avoiding medical treatment completely or substitute

for low quality medical treatment. But even if both of these coping strategies reduce the

financial burden caused by ill-health, they are not ideal, and may even enlarge the issue

(Prescott 1999).

The most common coping strategies applied by households impacted by ill-health and

disease in Sub-Saharan Africa are: intra- and inter-household labour substitutions,

engagement in labour activities other than normal work, financial borrowing from formal and

informal sources, use of savings, change of consumption patterns, and the sale of assets

(Chima et al. 2002, Lucas et al. 1999). Other structural factors which help households to cope

with consumption shocks can include a high level of adult literacy, accessibility of the

markets with regard to livelihood assets, and even the availability of electricity (Christiaensen

et al. 2005). Usually, coping strategies are defined as strategies adopted by family and

household members to minimise the impacts of ill-health on the welfare of all concerned

(Chima et al. 2002). Still, all these measures of crisis prevention, compensation and

substitution strongly rely on people's livelihoods and on the availability of livelihood assets.

It is usually not a question about whether assets are lost trough ill-health, but about the

amount and the value of the assets and about how fast they can get replaced.

3.4 The medical poverty trap

The insecurity of livelihoods and of the access to livelihood assets is also part of a poverty

circle which is driven, among other things, by ill-health and disease. However, livelihood

insecurity is not only a symptom of poverty and ill-health; it is a contributory cause

(Devereux 2001). This phenomenon has been already explained in Whitehead's et al. (2001)

definition about the medical poverty trap, which argues that ill-health may lead to poverty

and poverty may lead to ill-health. The medical poverty trap theory also focuses on

households and their micro-economy to analyse the economic impacts of diseases and ill-

health, and how these factors lead to poverty. Household expenditures created by ill-health

negatively affect household productions and earnings, investment and consumption patterns,

and household health and consumption, and finally can lead to poverty. Basically, being poor

often leads to ill-health, and in turn, ill-health and activities to prevent it also lead to reduced

income capacities (Nelson 1994). Nelson (1994) referred to this ongoing cycle under the term

"drift hypothesis", as ill-health can cause a downward drift in the socioeconomic status. This

assumption deeply correlates with the arguments put forward by Breyer et al. (2005).

Moreover, the consequences of ill-health on a household and its activities and survival

strategies can be quite complex, and affects most social and economic actions of a household

(Feachem et al. 1992).

Lwanga-Ntale et al. (2003) also highlight, that chronic poverty among individuals and

households, is often a consequence of poor health and poor health care systems.

Ill-health leads to the spending of household savings, to the sale of household assets such as

e.g. land and livestock, and to the decline of the household's labour power (Lwanga-Ntale et

al. 2003). Poor households affected by ill-health often need to apply strategies to survive this

difficult period and to cope with the economic burden caused by actions to improve the

health status. Sauerborn et al. (1996) analysed risk-management and coping strategies

applied by households in Sub-Saharan Africa. They found out that most poor households rely

on a mix of following economic strategies when affected by ill-health: intra-household

(labour) substitution, mobilisation of finances and household savings, sale of assets

(livestock), income diversification, and receiving loans and gifts from relatives and friends.

These coping strategies secure the economic survival and vitality of the household, but only

for a limited timeframe. If applied over a long period of time, coping strategies related to

severe and long-time ill-health would harm the microeconomic structure of a household, and

they would lead to household impoverishment (Sauerborn et al. 1996).

To overcome this cycle of ill-health and poverty, development interventions should

tackle household's vulnerability to ill-health and diseases as well as the reduction of poverty.

As poverty correlates with a lack of livelihood assets, any development intervention which

increases access to natural, social, and financial assets will indirectly support livelihood

security, and therefore break this cycle (Devereux 2001). The reduction of official and

unofficial costs and fees for health services, measures against corruption within the health

system, a less constricted access to health services, and a better management of public

finances could also be solutions to stop the medical poverty trap (Whitehead et al. 2001).

However, one of the aspects of the medical poverty trap which has been often

overlooked is the fact that people often cannot even get access to health services because

they are simply to poor or hardly own any livelihood assets. This issue should be taken into

consideration, as it is not uncommon for people to dispense medical treatment because of

their socioeconomic status (Obrist et al. 2007).

3.5 Rationale for the attention to the economic impact of diseases

There is a diverse range of reasons justifying increased research in relations between

development, economics, households, and ill-health caused by infectious diseases. Infectious

diseases are currently the major cause of mortality world wide and they already have a

significant impact on macro- and microeconomic structures (Philipson 1999). Furthermore, a

high level of good health and wellbeing among the average population is also a precondition

for any development activities. As already outlined, poor health and the prevalence of

infectious diseases slow down the productivity of individuals and of the community and the

wider society, and therefore can severely damage asset generating structures. Many

households especially in Sub-Saharan Africa are forced into persistent poverty because they

cannot cope anymore with the social, physical, and financial burdens of ill-health. Only if we

find out more about exactly how diseases impact households and their micro-economies, and

what kind of damage they cause (apart from physiological damage), will we be able to

efficiently create measures to alleviate the impact of ill-health and disease.

The evaluation of ill-health from an economic point of view is particularly important,

as economic analysis divides the health effects of public policies from those of private