Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Marine ecology progress series 530:119

Vol. 530: 119–134, 2015

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES

Published June 18

doi: 10.3354/meps11266

Mar Ecol Prog Ser

Habitat and trophic ecology of Southern Ocean

cephalopods from stable isotope analyses

Miguel Guerreiro1,*, Richard A. Phillips2, Yves Cherel3, Filipe R. Ceia1,

Pedro Alvito1, Rui Rosa4, José C. Xavier1,2

1MARE−Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade de Coimbra,

3004-517 Coimbra, Portugal

2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET,

3Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372 du CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, BP 14, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France

4Laboratório Marítimo da Guia, Centro de Oceanografia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa,

Av. Nossa Senhora do Cabo, 939, 2750-374 Cascais, Portugal

ABSTRACT: Although cephalopods play a critical role in marine food webs both as predators andprey, there is a limited knowledge of several basic aspects of their ecology, including their habitatand trophic level, in the Southern Ocean. We examined the ecological role of several SouthernOcean cephalopod species by analyzing δ13C and δ15N values in lower cephalopod beaks obtainedfrom diet samples of wandering albatross

Diomedea exulans from South Georgia (AtlanticOcean), and from Crozet and Kerguelen Islands (Indian Ocean). Beak δ13C values ranged from−25.7 to −17.9 ‰, and were used to assign different cephalopod species to the subtropical, sub-Antarctic or Antarctic Zones. Beak δ15N values were more variable among species, ranging from2.4 to 13.3 ‰, a difference of 11 ‰ that represents approx. 3 trophic levels. Differences amongislands in isotope ratios in the same cephalopod species (higher δ15N and lower δ13C values inSouth Georgia) were attributed to regional oceanographic processes. Antarctic cephalopodsoccupy niches similar to those found in some pelagic fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Ascephalopods are key components in Southern Ocean food webs, these results greatly advance ourunderstanding of the structure, energy and carbon flows in this polar ecosystem.

KEY WORDS: Southern Ocean · Pelagic ecosystem · Distribution · Foraging ecology ·

Kondakovia longimana · Diet

Resale or republication not permitted without written consent of the publisher

cephalopod species that thrive in the SouthernOcean are oegopsid squid and octo pods, including

Cephalopods play an important role in the marine

species that are entirely Antarctic, and other more

food web of the Southern Ocean (here defined as south

cosmopolitan species that either by active migration,

of the Subtropical Front; see Fig. 1). They are thought

or due to their deep-sea distribution, can cross the

to occupy the ecological niche of pelagic fish (Rod-

Antarctic Polar Front (APF) (Collins & Rodhouse

house & White 1995), and sustain large populations

2006). Southern Ocean cephalopods are those who

of top predators in the region (e.g. toothed whales,

live south of the Subtropical Front (STF) at around

seals, penguins, albatrosses and petrels), amounting

40° S (Fig. 1). Other longitudinal features in the

to an estimated total consumption of around 34 mil-

Southern Ocean include the Antarctic Circum polar

lion t of cephalopods per annum (Clarke 1983). The

Current (ACC), with a clockwise circulation around

*Corresponding author:

[email protected]

Inter-Research 2015 · www.int-res.com

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

the Antarctic continent in the Atlantic, Indian and

and about 2800 km from their colonies) (Imber 1992,

Pacific sectors of the Southern Ocean, which deflects

Weimerskirch et al. 1993, Xavier et al. 2004). Their

northwards at 50−52° S (thereafter resuming its east-

patchily-distributed prey are thought to include pri-

erly course) in the Atlantic sector, contributing to an

marily dead and moribund cephalopods that have

increase in local productivity (Deacon 1982, Trathan

floated to the surface post-spawning (Croxall &

et al. 1997). The other major oceanographic feature

Prince 1994, Cherel & Weimerskirch 1999, Xavier et

in the Indian sector which contributes to a local

increase in primary productivity is the Ker

Stable isotope analysis (SIA) of cephalopod beaks

Plateau, and also to some extent, the Crozet Islands.

gathered from the diet of top predators can provide

Despite their importance, knowledge of several

key ecological information (Cherel & Hobson 2005,

basic aspects of the ecology of cephalopods is lim-

Cherel et al. 2009b). SIA has been used increasingly

ited, particularly in terms of distribution and trophic

in the last 2 decades to study the structure of food

ecology (Xavier et al. 1999, Collins & Rodhouse

webs (e.g. Kelly 2000). With this approach, it is pos -

2006). One of the main reasons is the limited com-

sible to infer habitat and trophic level of organisms

mercial harvest, which reflects (1) the low number of

based, respectively, on the stable isotope ratios of

exploitable squid species, (2) the unpredictability of

13C to 12C (δ13C), and 15N to 14N (δ15N) (DeNiro &

their stocks, (3) a lack of knowledge of the abun-

Epstein 1978, 1981). In the pelagic waters of the

dance and distribution of relevant species, and (4) an

Southern Ocean, the carbon isotope ratio ultimately

inability to catch the faster-moving species. Ship-

reflects the influence of temperature on photosyn-

based scientific surveys in the Southern Ocean en -

thetic activity (Sackett et al. 1974), and CO2 avail -

counter similar problems, not helped by the low trawl

ability, leading to a broad δ13C latitudinal gradient

speeds and use of conventional sampling methods

in baseline values from equatorial to polar waters,

(Clarke 1977, Rodhouse 1990, Rodhouse et al. 1996).

which is propagated through the food chain (Cherel

The available information on diet and trophic rela-

& Hobson 2007, Jaeger et al. 2010, Quillfeldt et al.

tionships is therefore limited largely to 2 common

2010). In contrast, the ratio of the stable isotopes of

species,

Martialia hyadesi and

Moroteuthis ingens

nitrogen can be used to estimate the trophic level of

(Jackson et al. 2007), and otherwise biased towards

an organism, as there is a stepwise enrichment of 15N

cephalopods that feed on Antarctic krill

Euphausia

between prey and predators (Montoya 2007).

superba, as these are caught in the same nets (Nemoto

The objectives of this study were to:

et al. 1985, 1988).

(1) Characterize the habitat and trophic level of the

An alternative approach to study Southern Ocean

cephalopod fauna of the Atlantic and Indian sectors

cephalopods, and to overcome these sampling prob-

of the Southern Ocean by analysing the δ13C and

lems, is to use seabirds that are cephalopod preda-

δ15N values of cephalopod beaks (obtained from the

tors, such as albatrosses (Cherel & Weimerskirch

boluses [pellets] and induced regurgitations of wan-

1995, Xavier et al. 2003a). In general, albatrosses are

dering albatrosses) as proxies for water mass (latitu-

an excellent sampling tool for this kind of study be -

dinal distribution) and trophic level, respectively;

cause (1) they feed on a great number and diversity

(2) Compare the trophic niche of these cephalo

of cephalopods (Cherel & Klages 1998), (2) they

pods based on stable isotope ratios with the few cur-

breed in high densities on land and so are readily

rent conventional diet studies;

available for diet sampling, (3) they do not fear

(3) Assess if each cephalopod species occupies the

humans and are therefore easy to work with, (4) they

same niche throughout the Southern Ocean;

forage over and therefore sample large areas of the

(4) Determine if any cephalopods occupy a similar

ocean, and (5) chicks and adults retain undigested

niche to top fish predators.

cephalopod beaks in their stomachs for long periodsof time. In the present study, we investigated thecephalopod fauna of the south Atlantic and Indian

MATERIALS AND METHODS

sectors of the Southern Ocean using diet samples col-lected from wan dering albatrosses

(Diomedea exu-

lans) breeding at South Georgia, Crozet and Kergue-len islands. The wandering albatross feeds on a large

Cephalopod beaks were collected from boluses

variety of ce phalopod species on long foraging trips

(from chicks) or induced regurgitations (from adults)

that during the chick rearing period range from

of wandering albatrosses during the breeding season

Antarctic to subtropical waters (between 25−64° S

at South Georgia (54° S, 38° W; south of the APF), Ker-

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

guelen (49° S, 69° E, in the vicinity of the APF) and

Stable isotope analysis

Crozet islands (46° S, 51° E, north of the APF) (Park etal. 1993) (Fig. 1). All samples were collected from

We analyzed the stable isotope ratios of the

September to December 1998, during the latter part

cephalopod species that were represented by at least

of the 8−9 mo chick-rearing period.

10 lower beaks from one of the island groups. For

At South Georgia, the samples consisted of bo

each species at each island, 10 beaks in good condi-

luses, which are voluntarily regurgitated by chicks

tion were randomly selected, with the exception of

prior to fledging (Xavier et al. 2003a). These com-

Taningia danae (a rare species) with only 5 speci-

prise the indigestible parts of prey consumed during

mens from Kerguelen, and

Haliphron atlanticus (the

the winter, from hatching in March or April to fledg-

only octopod species) with 11 specimens from South

ing in November or December (Xavier et al. 2003b,

Georgia. In addition, to assess local ontogenic dif

2005, Xavier & Croxall 2007). Diet samples from

ferences in

Histioteuthis atlantica, 2 size-classes of

Crozet and Kerguelen were obtained by induced

beaks were compared (large and small), which dif-

regurgitation immediately after the chick was fed

fered in LRL at the same island (for Kerguelen and

by one of its parents (Cherel & Weimerskirch 1999).

South Georgia) by a mean of 2 mm. Prior to the

Samples were frozen at −20°C and subsequently

analysis, the whole beaks were dried at 60°C and

analyzed in the laboratory. The beaks obtained from

ground into a fine powder; due to an oversight, infor-

each sample were cleaned, separated into upper

mation on individual beak identity was not retained

and lower beaks, and counted. When possible, the

and so it was not possible to relate LRL to subsequent

lower beaks were identified to species level (Xavier

measurements. Sub-samples (ranging from 0.30−

& Cherel 2009) and the lower rostral length (LRL)

0.55 mg) of each beak were placed in a tin capsule

was measured. Beak identification was confirmed

and the stable isotope values were measured using a

with reference to collections at the British Antarctic

Flash EA 1112 Series elemental analyzer coupled

Survey and Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé.

online via a Finnigan ConFlo II interface to a Delta V

Cleaned beaks were kept in 70% ethanol until iso-

S mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Analysis of

topic analysis.

the whole beak provides an integrated, lifetime sig-nal of diet and geographic position, although biasedtowards more recent periods, when mass incrementsare greater, rather than to younger ages. The carbonand nitrogen isotope ratios were expressed in delta(δ) notation relative to Vienna PDB limestone for δ13Cand atmospheric nitrogen (AIR) for δ15N, respec-tively. Replicate measurements of internal laboratorystandards (acetanilide) indicated measurement errorsof < 0.15 ‰ for both δ13C (−28.38 to −27.73 ‰) andδ15N (1.76−2.41‰) values.

Samples with δ13C values greater than −19.5 ‰

were considered to have a subtropical distribution(north of the Subtropical Front), and those with val-ues less than −22.9 ‰ were considered to be fromAntarctic waters (south of the APF) (Cherel & Hobson2007, Jaeger et al. 2010); those with intermediate values (between −22.9 and −19.5 ‰) were consideredto be of sub-Antarctic origin. Habitat assignmentswere based on the estimated isotopic positions of

Fig. 1. Map of the Southern Ocean indicating the sampling

APF and STF based on stable isotope ratios in plasma

sites at South Georgia, Crozet and Kerguelen, and the

sampled from albatrosses (Jaeger et al. 2010), and

1000 m isobath (dark grey line). Antarctic Polar Front (PF),

blood from penguins (Cherel & Hobson 2007). These

Sub-Antarctic Front (SAF), and Subtropical Front (STF)

are the main oceanic fronts (black line patterns)

cut-offs may not be as appropriate for cephalopods,

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

even though these are depredated by albatrosses,

due to differences in trophic levels and in tissue- andspecies-specific isotopic discrimination factors. There -

Lower beaks (n = 384) of 16 species collected at the

fore, we adopted a conservative approach, distin-

3 island groups (i.e. South Georgia, Crozet and Ker-

guishing Antarctic and subtropical species of cephalo -

guelen) from the Atlantic and Indian sectors of the

pods based on the highest δ13C value of the 2 studies

Southern Ocean were included in the study. These

for the STF (−19.5 ‰

Eudyptes chrysocome moseleyi

species comprised 95% of the total number of lower

blood; Cherel & Hobson 2007) and the lowest δ13C for

beaks found in the diet samples of wandering alba-

the APF (−22.9 ‰

Diomedea exulans plasma; Jaeger

trosses (cephalopod component) from all 3 sites

et al. 2010).

(J. Xavier and Y. Cherel unpubl. data).

Albatrosses have long foraging distances, and so

sample cephalopods over a wide latitudinal range.

As the δ13C of their squid prey will reflect the point of

Beak δ

13C values

origin of the squid, differences in foraging ranges ofthe individual birds per se should not affect our

δ13C values in the beaks of individual cephalopods

results or conclusions.

ranged from −25.7

(Kondakovia longimana, SouthGeorgia) to −17.9 ‰

(Histioteuthis atlantica, Kergue-len) (Table 1, Figs. 2–4). The species displaying high-

Stable isotope niches and isotope metrics

est values was

H. atlantica (Crozet; mean: –18.6 ‰),and the lowest were found in

Batoteuthis skolops

Corrected standard ellipse areas (SEAc) and

(South Georgia; mean: –24.4 ‰). When compared

Bayesian standard ellipse areas (SEAb) were calcu-

among localities, significantly lower δ13C values were

lated in order to examine inter- and intra-specific

found in samples of

B. skolops,

Galiteuthis glacialis,

niche size and overlap. Overlap among species pairs

Histioteuthis eltaninae and

K. longimana from South

was categorized as high (area of overlap ≥ 50% of the

Georgia (p < 0.05 in all cases) (Table 2). The highest

smaller niche area) or low (area of overlap < 50% of

δ13C values for

H. atlantica (large size) and

Martialia

the smaller niche area). Standard ellipse areas were

hyadesi were found in samples from Kerguelen.

plotted for visualization of the data, using the SIAR

Beak δ13C values for

Moroteuthis knipo vitchi were

package for R (Parnell et al. 2010, Jackson et al.

significantly greater in samples from Crozet than

Kerguelen (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Beak δ

15N values

All statistical analyses used a significance level of

Beak δ15N values of individual cephalopods ranged

α = 0.05, and were performed using R. ANOVAs and

from 2.4 ‰

(M. hyadesi, Crozet) to 13.3 ‰

(Gonatus

t-tests were conducted to test for differences in stable

antarcticus, South Georgia) (Table 1, Figs. 2–4). The

isotope ratios in squid beaks collected at the different

species with highest values for δ15N was

Cicloteuthis

island groups. Data on

Martialia hyadesi were trans-

akimush kini (Crozet: mean: 12.2 ‰) and the lowest

formed exponentially to fit the assumptions of normal

values were for

M. hyadesi (Crozet; mean: 3.6 ‰).

distribution and homoscedasticity. Results of statisti-

When compared to other sites, significantly higher

cal tests are presented as

t-values, both for the

t-tests

values of δ15N were observed for

G. antarcticus and

and ANOVAs, as the post hoc test used was the pair-

small

H. atlantica, and lower values for

B. skolops at

wise Tukey HSD. Principal components analysis

South Georgia (p < 0.05 in all cases) (Table 3). Higher

(PCA) (extracted from the variables average LRL,

δ15N values were obtained for

Taonius sp. (Clarke) and

δ13C and δ15N of each group [island populations]

M. hyadesi from Kerguelen (p < 0.05 in all cases)

covariance matrix), and cluster analysis (CA) (stan-

(Table 3). The lowest mean δ15N value for samples of

dardized variables, Ward's linkage) were used to

Taonius sp. B (Voss) was obtained for beaks sampled at

assess segregation of various species throughout the

Crozet (p < 0.05) (Table 3). Moreover, δ15N values in

H.

Southern Ocean according to the average δ13C and

eltaninae were higher at South Georgia than at Ker -

δ15N of each group. As beaks from

Haliphron atlanti-

guelen. In contrast, δ15N values in

K. longimana from

cus were eroded, mean LRL (for PCA) was obtained

Kerguelen were higher than those from South Georgia,

from Xavier et al. 2003b.

whereas those in ?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke) and

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

osses at South Geor

guelen Islands. nd = not deter

N values, and C:N ratios of the main squid species found in the diet of wandering albatr

ozet Islands, and Ker

on atlanticus

oteuthis antar

oteuthis antar

tialia hyadesi

oteuthis ingens

oteuthis antar

tialia hyadesi

aningia danae

Gonatus antar

Gonatus antar

Gonatus antar

stral length (LRL) and beak o

ozet Islands

South Geor

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

–26 –24 –22 –20 –18

–26 –24 –22 –20 –18

Fig. 2. Plotted distribution of the δ15N and δ13C in beaks of

Fig. 3. Plotted distribution of the δ15N and δ13C in beaks of

the squid species from Crozet Islands. Blue and red vertical

the squid species from Kerguelen. Blue and red vertical

lines indicate estimated δ13C values corresponding to the

lines indicate estimated δ13C values corresponding to the

Antarctic Polar (PF) and Subtropical fronts (STF), respec-

Antarctic Polar (PF) and Subtropical fronts (STF), respec-

tively. Bayesian standard ellipse areas are displayed for the

tively. Bayesian standard ellipse areas are displayed for the

various cephalopod species: Allu =

Alluroteuthis antarcticus,

various cephalopod species: Allu =

Alluroteuthis antarcticus,

Bato =

Batoteuthis skolops, Eltan =

Histioteuthis eltaninae,

Bato =

Batoteuthis skolops, Cyclo =

Cycloteuthis akimush -

Galit =

Galiteuthis glacialis, Gonat =

Gonatus antarcticus,

kini, Eltan =

Histioteuthis eltaninae, Galit =

Galiteuthis

H.atlantL =

Histioteuthis atlantica (large), Ingens =

Moro-

glacialis, Gonat =

Gonatus antarcticus, H.atlantL =

His -

teuthis ingens, Knipo =

Moroteuthis knipovitchi, Konda =

tioteuthis atlantica (large), H.atlants =

Histioteuthis atlan -

Kondakovia longimana, Mart =

Martialia hyadesi, Mast =

tica (small), Knipo =

Moroteuthis knipovitchi, Konda =

?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke), Taon =

Taonius sp. (Clarke),

Kondakovia longimana, Mart =

Martialia hyadesi, Taning

TaonB =

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

=

Taningia danae, Taon =

Taonius sp. (Clarke), TaonB =

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

M. knipovitchi from South Georgia were higher thanthose found at Crozet (p < 0.05 in all cases) (Table 3).

antarcticus,

G. glacialis,

H. eltaninae, ?

Mastigoteuthissp. A (Clarke),

Hali phron atlanticus). Species nichesize (SEAc) varied from < 0.5 (e.g.

M. ingens = 0.2,

H.

Stable isotope niches and isotope metrics

atlanticus = 0.3) to > 4 (e.g.

G. antarcticus of SouthGeorgia = 4.5,

K. longimana of Kerguelen = 4.8).

The cephalopod fauna of the Southern Ocean was

The degree of overlap in isotopic niche differed

represented by 3 major groups (Figs. 2–5) of species

among the 3 island groups depending on the spe-

with overlapping niches and 1 outlier: (1) medium

cies, especially comparing between South Georgia

δ15N and δ13C values

(K. longimana,

M. knipovitchi,

and the other sampling sites (Crozet and Kerguelen

Moroteuthis ingens,

Alluroteuthis ant

Islands). Isotopic niches of specimens from Crozet

glacialis,

H. eltaninae, ?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke),

showed either a low overlap with the same species

Haliphron atlanticus), (2) high δ15N and average δ13C

at the other 2 sites, a high overlap between Crozet

values

(B. skolops,

G. antarcticus,

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

and Kerguelen

(B. skolops,

H. eltaninae,

K. longi-

and

Taningia danae), and (3) high δ15N and δ13C val-

mana,

Histioteuthis atlantica large), or a high over-

ues

(Histioteuthis atlantica,

Taonius sp. [Clarke] and

lap between Kerguelen and South Georgia

(M.

C. akimushkini), and the outlier

M. hyadesi (ex-

knipo vitchi,

Taonius sp. B [Voss]). Regardless of the

tremely low δ15N) (Figs. 3–5). The first group can be

overlap, the overall isotopic niche sizes, however,

further divided into 2 sub-groups: (1) species with

seemed to be similar across sites. The exceptions

lower δ13C values that show low overlap

(K. longi-

were a few species at Crozet which had isotopic

mana,

M. knipo

vitchi), and (2) species with higher

niches that were smaller than at the other

δ13C values and high levels of overlap

(M. ingens,

A.

groups

(K. longimana and

H. eltaninae).

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

The first 2 principal components (PC) explained

> 89% of the overall variance (Fig. 6). Mean LRL

loaded heavily and positively on the first axis (PC1),

and mean δ15N (and to a lesser extent mean δ13C)

loaded heavily and positively on the second axis

(PC2) (Fig. 6). Large species tended to be associated

with a positive score on PC1, whereas subtropical

species tended to be associated with a positive score

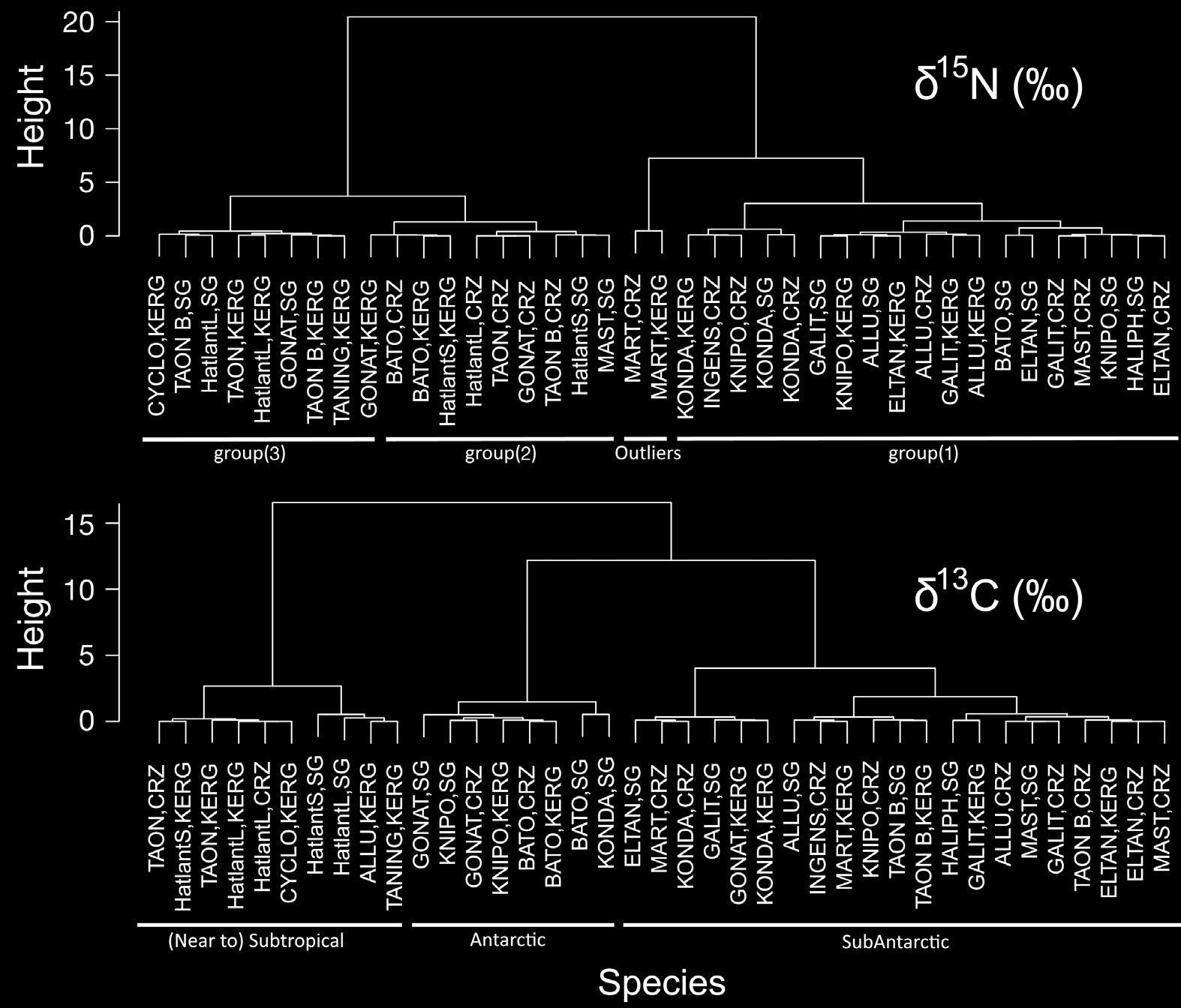

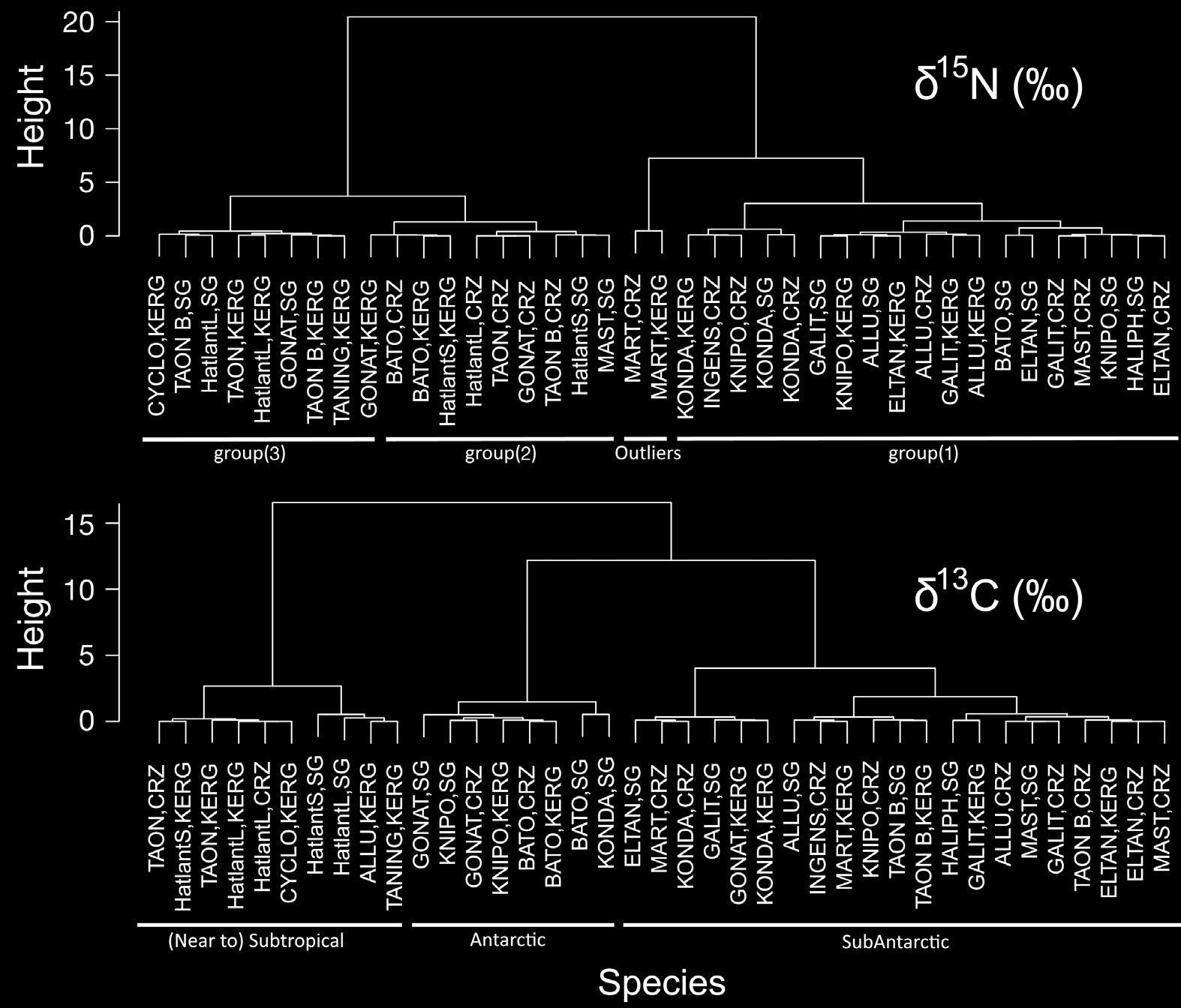

on PC2 (Fig. 7). The 2 dendrograms produced by the

CA (Fig. 8), showed 2 different aggregation patternsaccording to the SI ratio used: a clear separation near

the top (root) between species with high and lowδ15N (2 groups), and 3 separate groups of species

based on δ13C values.

–26 –24 –22 –20 –18

Fig. 4. Plotted distribution of the δ15N and δ13C in beaks ofthe squid species from South Georgia. Blue and red vertical

The results indicate that δ13C tended to be lower,

lines indicate estimated δ13C values corresponding to the

δ15N tended to be higher, and that both ratios showed

Antarctic Polar (PF) and Subtropical fronts (STF), respec-tively. Bayesian standard ellipse areas are displayed for the

higher variance in the lower beaks of cephalopods

various cephalopod species: Allu =

Alluroteuthis antarcticus,

from South Georgia compared to conspecifics in the

Bato =

Batoteuthis skolops, Eltan =

Histioteuthis eltaninae,

Indian sector of the Southern Ocean. Based on the sta-

Galit =

Galiteuthis glacialis, Gonat =

Go natus antarcticus,

ble isotope data, the cephalopods in the diet of the

Haliph =

Haliphron atlanticus, H.atlantL =

Histioteuthisatlantica (large), H.atlants =

Histioteuthis atlantica (small),

wandering albatross were from 3 water masses (Ant -

Knipo =

Moroteuthis knipovitchi, Konda =

Kondakovia

arctic, sub-Antarctic and subtropical), and spanned

longimana, Mast = ?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke), TaonB =

over 3 trophic levels from

Martialia hyadesi to

Gona-

Taonius sp. (Clarke)

tus antarcticus (based on δ15N range divided by 3.3,where 3.3 equals the stepwise enrichment in δ15Nfrom prey to predator/consumer [Wada et al. 1987]).

Table 2. Tests (

a posteriori) comparing δ13C values of the squid sampled at South Georgia (SG), Crozet (CRZ) and Kerguelen

(KRG). Tests: A = ANOVA, Tukey tests (2 df); T =

t-test (1 df); ns = non-significant; blank cell = non-existent pair

Taonius sp. (Clarke)

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

Histioteuthis atlantica small

Histioteuthis atlantica large

?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke)

Martialia hyadesi

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

Table 3. Tests (

a posteriori) comparing δ15N values of the squid sampled at South Georgia (SG), Crozet (CRZ) and Kerguelen(KRG). Tests: A = ANOVA, Tukey tests (2 df); T =

t-test (1 df); T(EXP) =

t-test on exponentially transformed variables (1 df);

ns = non-significant; blank cell = non-existent pair

Taonius sp. (Clarke)

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

Histioteuthis atlantica small

Histioteuthis atlantica large

?

Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke)

Martialia hyadesi

The ce phalopod community appeared to consist of 3separate assemblages (average δ15N and δ13C, high

δ15N and low δ13C, high δ15N and δ13C) and one outlier,

M. hyadesi. Furthermore, the cephalopod community

showed significant intra-specific differences in their

isotopic niches associated with the island group.

Beak δ

13C values and biogeography

The low δ13C found in squid beaks collected at

South Georgia may be due to the higher latitude of

the sampling location compared to Crozet and Ker-

–26 –24 –22 –20 –18

Fig. 5. Plotted distribution of the δ15N and δ13C in beaks of thesquid species from the Southern Ocean. Blue and red vertical

lines indicate estimated δ13C values corresponding to theAntarctic Polar (PF) and Subtropical fronts (STF), respec-tively. Bayesian standard ellipse areas are displayed for the

various cephalopod species: Allu =

Alluroteuthis ant arcticus,Bato =

Batoteuthis skolops, Cyclo =

Cycloteuthis aki mush -kini, Eltan =

Histioteuthis eltaninae, Galit =

Galiteuthis gla -

2nd Component (24% variance) –1.0

cialis, Gonat =

Gonatus antarcticus, Haliph =

Haliphron at-lanticus, H.atlantL =

Histioteuthis atlantica (large), H.atlants

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

=

Histioteuthis atlantica (small), Ingens =

Moroteuthis in-

1st Component (65% variance)

gens, Knipo =

Moroteuthis knipovitchi, Konda =

Konda ko vialongimana, Mart =

Martialia hyadesi, Mast = ?

Mastigoteuthis

Fig. 6. Loadings on the first 2 principal components (PC1

sp. A (Clarke), Taning =

Taningia danae, Taon =

Taonius sp.

and PC2) for the mean values of variables lower rostral

(Clarke), TaonB =

Taonius sp.B (Voss)

length (LRL), δ13C and δ15N

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

Fig. 7. Individual principal component scores (from PC1 and

PC2 displayed in Fig. 6) of each sample area (SG = South

Georgia, CRZ = Crozet Islands, KRG = Kerguelen Islands)

and squid species:

= Alluroteuthis antarcticus, =

teuthis skolops, =

Histioteuthis eltaninae, =

glacialis, =

Gonatus antarcticus, =

Histioteuthis atlan tica

Histioteuthis atlantica (small), =

ingens, =

Moroteuthis knipovitchi, =

Konda kovia longi-

Martialia hyadesi, =

?Mastigoteuthis sp. A

Taonius sp. (Clarke),

= Taonius sp. B (Voss),

= Cycloteuthis akimushkini, =

Taningia danae, =

Fig. 8. Dendrograms produced by Cluster Analysis (using standardized variables and Ward's linkage method) showing aggre-gations of species and sample areas (SG = South Georgia, CRZ = Crozet Islands, KERG = Kerguelen) based on δ15N (upperpanel) and δ13C (lower panel) data, and their functional classification (below each dendrogram). ALLU = Alluroteuthis antarcti-cus, BATO = Batoteuthis skolops, CYCLO = Cycloteuthis akimushkini, ELTAN = Histioteuthis eltaninae, GALIT = Galiteuthisglacialis, GONAT = Gonatus antarcticus, HALIPH = Haliphron atlanticus, HatlantL = Histioteuthis atlantica (large), HatlantS =Histioteuthis atlantica (small), INGENS = Moroteuthis ingens, KNIPO = Moroteuthis knipovitchi, KONDA = Kondakovia longi-mana, MART = Martialia hyadesi, MAST = ?Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke), TANING = Taningia danae, TAON = Taonius sp.

(Clarke), TAON B = Taonius sp. B (Voss)

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

guelen (south vs. north of the APF, respectively).

Also, some squid from higher latitudes (e.g. Moro-

teuthis knipovitchi, Table 4) in Kerguelen showed

lower δ13C values than the same species from the

lower latitude site at Crozet. However, this was not

true in all species (e.g. M. hyadesi and Histioteuthis

atlantica, Table 4), possibly due to the higher base-line

δ13C of the Kerguelen Plateau (Trull et al. 2008).

To enable comparison with other studies, the mean

isotope ratio in soft tissue was estimated, by subtract-

ing 0.75 ‰ from the δ13C values measured in the

beaks (Hobson & Cherel 2006). These corrected val-

n Ocean and infer

ues and their assigned distribution (Cherel & Hobson

; ?: no known distribution for this species

2007, Jaeger et al. 2010) was then contrasted with

previous assessments (Xavier et al. 1999, Collins &

Known distribution

Rodhouse 2006, Xavier & Cherel 2009) (Table 4).

Cephalopod species that were previously considered

to live at high latitudes (according to Xavier et al.

1999, our Table 4) — Batoteuthis skolops, Kondakovia

osses in the Souther

longimana and M. knipovitchi — had the lowest mean

δ13C (and high standard deviations, except for B.

skolops). Surprisingly, G. antarcticus also displayed

very low values, despite previous evidence that it ismostly distributed in northern sub-Antarctic waters

ssessed water mass

(Xavier et al. 1999, Collins & Rodhouse 2006). The

high standard deviation in δ13C recorded in K. longi-

mana and M. knipovitchi, and low mean values in

opical waters (see Fig. 1); Cos.: cosmopolitan

G. antarcticus can be explained by a broader distri -bution of these species, including north and south of

the APF, in agreement with Cherel & Weimerskirch

(1999). Therefore, these 3 species (K. longimana, M.

knipovitchi and G. antarcticus) are distributed across

the APF (both in Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters),

whereas B. skolops is found exclusively in Antarctic

waters (Fig. 5, Table 4). The so-called subtropical spe-

cies that were sampled (Taonius sp. [Clarke], Taonius

sp. B [Voss 1980], Cycloteuthis akimushkini and His-tioteuthis atlantica [Voss et al. 1998]) (Table 4), were

those with the highest δ13C, indicating distributions

that are around and to the north of the STF (Fig. 5,

ctic; Sub-Ant.: sub-Antar

δ13C values typical of sub-Antarctic waters were ob-

tained for numerous species (Haliphron atlanticus,

on atlanticus

Taningia danae, M. ingens, M. hyadesi, H. eltani-

oteuthis antar

nae, Taonius sp. B [Voss], Alluroteuthis antarcticus,

tialia hyadesi

oteuthis ingens

C in the mantle (muscle) of the main squid species in the diet of wandering albatr

aningia danae

Galiteuthis glacialis and ?Mastigoteuthis sp. A

Gonatus antar

[Clarke]) (Fig. 5, Table 4). Collins & Rodhouse (2006)and Xavier et al. (1999) considered that A. antarcticusand G. glacialis live primarily in Antarctic waters;

however, our isotopic data suggest that some indi

viduals inhabit sub-Antarctic waters (Table 4).

Furthermore, clustering of species based on

es-ence, 0 = absence. Ant.: Antar

able 4. Estimated

(Fig. 8), supports the biogeographic assessment dis-

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

cussed above. The 3 clusters distinguished in that

skolops, G. antarcticus, Taonius sp. B (Voss) and

analysis correspond unequivocally to cephalopods

Taningia danae; and finally (3) the subtropical squid

originating from Antarctic, sub-Antarctic or (near to)

C. akimushkini, Histioteuthis atlantica and Taonius

subtropical waters.

sp. (Clarke). This classifi cation is confirmed by themultivariate analysis (Figs. 7 & 8), which distin-guished 2 large, well-defined groups (with M. hya -

Beak δ15N values and trophic relationships

desi and group (1) in the first, and groups (2) and (3)in the second) (Fig. 8).

Several cephalopod species showed higher δ15N

By correcting the measured δ15N values for beaks

in samples from South Georgia than from the other

to provide estimates for soft tissue (by adding 4.86 ‰;

island groups (especially Crozet), which suggests

Hobson & Cherel 2006), and comparing these re sults

that either squid at South Georgia have different

with muscle samples collected in previous studies in

feeding preferences (higher trophic level) from those

the same regions (Tables 5 & 6), it is possible to infer

in the Indian Sector, or there are regional differences

potential prey. However, this is with the caveat that

in primary productivity that lead to differences in

these correction factors may not be appropriate for all

δ15N baselines between regions, relating to the rela-

species. Nevertheless, the most probable niches occu-

tive dominance of eukaryote vs. prokaryote (auto-

pied by these animals are as follows. M. hyadesi is

trophic) production (Fawcett et al. 2011). Regardless,

known to feed mainly on hyperiid am

the present study largely confirms previous findings

myctophid fish, and to a lesser extent on cephalo

based on stable isotope analysis for most of the stud-

pods, including a degree of cannibalism (Rodhouse

ied species (Cherel & Hobson 2005, Cherel et al.

et al. 1992). Since myctophid fish tend to be at a sim-

2008), with the exception of K. longimana and G.

ilar or higher trophic level based on nitrogen isotope

antarcticus, for which δ15N values were higher than

ratios (Tables 5 & 6) (Cherel et al. 2008), it seems that

those recorded previously (Wada et al. 1987, Cherel

M. hyadesi feeds on myctophids in lower quantities

& Hobson 2005, Cherel et al. 2008).

than previously suggested, at least in the southern

The distribution of δ15N in the different species

Indian Ocean. K. longimana presented very low δ15N

suggested 3 distinct groups and one outlier (M.

values (and high LRL; Fig. 7), but not low enough

hyadesi). The 3 groups were: (1) the onychoteuthid

to be entirely dependent on euphausiids (Table 5)

squids (with the lowest δ15N values, especially K.

(Nemoto et al. 1985, 1988), and thus its diet seems

longimana) plus Haliphron atlanticus, H. eltaninae,

likely to include some prey with low δ15N values such

cialis; (2) ?Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke), B.

as crustaceans and myctophid fish (Table 6) (Kaehler

Table 5. Estimated δ15N values in mantle (muscle) of the main squid species in the diet of wandering albatrosses at South Georgia, Crozet

Kerguelen Islands

Taonius sp. (Clarke)

Taonius sp. B (Voss)

Histioteuthis atlantica small

10 15.2 ± 1 13.7−16.9

Histioteuthis atlantica Large

?Mastigoteuthis sp. A (Clarke)

10 13.6 ± 1 12.3−15.1

Martialia hyadesi

Taningia danae

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

Table 6. Trophic level and δ15N of squid, crustacea and marine vertebrates sampled in previous studies in the Southern Ocean

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Prince Edward Is.

Kaehler et al. (2000)

Euphausia superba

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Euphausia frigida

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Martialia hyadesi

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel & Hobson (2005)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Pauly et al. (1998)

Burns et al. (1998)

Zhao et al. (2004)

Hydrurga leptonyx

Hall-Aspland et al. (2005)

Zhao et al. (2004)

Anderson et al. (2010)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

Diomedea exulans

Anderson et al. (2010)

Jaeger et al. (2010)

Anderson et al. (2010)

Cherel et al. (2013)

Anderson et al. (2010)

Cherel et al. (2007)

Cherel et al. (2008)

Cherel et al. (2007)

Stowasser et al. (2012)

aAdélie Land; bCorrected (beak) values; cRaw (beak) values

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

et al. 2000, Cherel et al. 2008, Stowasser et al. 2012).

subtropical waters (Altabet & François 1994, Jaeger

M. ingens (and M. knipo vitchi) had a similar niche to

et al. 2010). C. akimushkini had the highest mean

K. longimana (Table 5), which was also within the

δ15N value of all species, and there was a positive

expected range for a diet dominated by mesopelagic

relationship between individual size and δ15N in H.

fish (myctophids and paralepids, Table 6) (Cherel &

atlantica (Table 1, Fig. 7). This squid feeds higher in

Duhamel 2003).

the food chain as it grows and is able to feed on pro-

The cephalopods which had the lowest δ15N (apart

gressively larger prey. Thus, ontogenetic variation

from M. hyadesi and the onychoteuthids, Table 5)

has a potentially marked impact on δ15N values in

are likely to depend on zooplankton that feed in turn

histioteuthids as it does in other species of ommas-

on sinking organic matter, since the measured δ15N

trephids and onychoteuthids (Cherel & Hobson 2005,

values were higher than expected from organisms

Cherel et al. 2009a, Lorrain et al. 2011).

that, in some cases, are characterized by gelatinous

Even though the various squid species in this study

bodies and small size (except for Haliphron atlanticus,

showed significant intra-specific differences in their

Fig. 7), e.g. cranchiids (Collins & Rodhouse 2006).

niches across island groups, they generally remained

The sinking organic matter and detritus is generally

in the same relative positions within the respective

enriched in 15N as a consequence of microbial

cephalopod communities. The exception was ?Masti -

decomposition during the transport to depth, which

goteuthis sp. A (Clarke) which moved between the

richment in the whole food web

first group in Crozet to the second group in South

(including cephalo

pods) that is dependent on this

Georgia (Figs. 2, 3, 4 & 8).

resource (Michener & Kaufman 2007).

Overall, the squid that live in Antarctic and sub-

G. antarcticus presented the highest δ15N of all

Antarctic waters were secondary to tertiary con-

cephalopods in this study (apart from T. danae and

sumers, i.e. trophic level (TL) > 3, which is near the

the subtropical squids, Table 5). These high δ15N

average level for marine mammals (TL = ca. 4.0

values are just below those for the colossal squid

[Pauly et al. 1998]), penguins (TL = 3.4−4.0 [Sto

Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni (Cherel & Hobson 2005,

wasser et al. 2012]) other seabirds (TL = 3.7−5.2 [Sto -

Cherel et al. 2008) (Table 6), which is considered a

wasser et al. 2012]), and sharks (TL > 4 [Cortés 1999])

top invertebrate predator (Cherel & Hobson 2005)

(Table 6). Furthermore, the range of isotopic niches

that feeds on large fish and squid, and is found in the

occupied by squid, and their wide horizontal and

diet of sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus and

vertical distribution, shows parallels with the niches

sleeper sharks Somniosus cf. microcephalus (Clarke

occupied by large pelagic fish (Rodhouse & White

1980, Cherel et al. 2004) (Table 6). This may probably

1995, Cortés 1999). Indeed, at depth, squid may be

be explained by a top predator position (by G.

competing for prey with large, deep-diving mammals

antarcticus) on a rather inefficient food web charac-

such as seals (Cherel et al. 2008). The most likely

terized by high 15N enrichment rates, dependent on

candidates for occupying the niche of large pelagic

heterotrophy of organic matter and detritus descend-

fish are the squids with the highest δ15N that do not

ing from epipelagic waters. As they are muscular

belong to the cranchiid or the mastigoteuthid/bato-

squid with well-developed hooks, which is a sign of

teuthid families, as the former are gelatinous and

an active predator among squid, this species is a can-

likely to be sluggish (Collins & Rodhouse 2006) and

didate for top predator within this environment (ac -

the latter probably depend on the benthos (Roper &

cording to the isotope data), despite their small size

Vecchione 1997); hence, the most active predators

relative to such megafauna as T. danae (Fig. 7) and M.

are presumably G. antarcticus, T. danae and M.

knipovitchi (Figs. 2–5).

T. danae is certainly one of the top predators

amongst the squid inhabiting the deep ocean (Cherelet al. 2009b), as it shows a nitrogen isotope ratio at

least as high as the giant squid Architeuthis dux, andwithin the range recorded in other studies (Cherel

In conclusion, our study emphasizes that cephalo -

& Hobson 2005, Cherel et al. 2009b) (Tables 5 & 6). T.

pods have a wider and generally more complex (but

danae can also reach a considerable size (Fig. 7),

well defined) pattern of distribution around the

with a maximum mantle length of 170 cm (Nesis

Southern Ocean than previously considered. Given

1987). The subtropical species Histioteuthis atlantica,

the large range of δ13C and δ15N values, cephalopods

mush kini and Taonius sp. (Clarke) had the

must occupy a diverse range of niches, from the mid-

highest δ15N, probably due to the high baseline in

dle of the food web (secondary consumers, TL = 3), to

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

top predators (TL > 4) in all the different water

masses of the Southern Ocean. δ15N in our samples

ingens (Teuthoidea: Onychoteuthidae) in the upperslope waters of the Kerguelen Islands. Mar Ecol Prog Ser

corresponded broadly to those expected from previ-

ous conventional diet studies, or, with the exception

of Martialia hyadesi, were somewhat higher, sug-

predators: a new tool to study the trophic ecology of

gesting a greater representation of higher trophic

cephalopods, including giant and colossal squids. Proc RSoc B 272: 1601−1607

prey. Although particular squid varied in their iso-

topic niche depending on the sampling site (island

bon stable isotope signatures of marine predators: a tool

group), they did, however, occupy the same relative

to investigate their foraging areas in the Southern

position within each community, apparently consist-

Ocean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 329: 281−287

ing of 3 main groups and one outlier (M. hyadesi).

Cherel Y, Klages N (1998) A review of the food of alba-

trosses. In: Robertson G, Gales R (eds) Albatross biology

The most active, muscular and best-armed (hooked)

and conservation. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping

cephalopod species with the highest δ15N levels seem

Norton, Australia, p 113–136

likely to occupy the niche of a top predator in pelagic

ecosystems. Squid in general constitute a crucial and

marine resources: black-browed albatrosses feeding onommastrephid squids in Kerguelen waters. Mar Ecol

diverse component of Southern Ocean ecosystems,

Prog Ser 129: 295−300

as not only are they widespread and abundant prey

for marine top predators, but in addition, the meso-

teuthid squids in the southern Indian Ocean: new infor-

and bathypelagic species function as effective bio-

mation from seabird predators. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 188: 93−104

logical circulators by returning deep-sea carbon

back to the surface, and vice-versa. Finally, our study

subantarctic islands:

new information from predators.

demonstrates the value of new approaches for im

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 266: 143−156

proving our understanding of the role of cephalopods

in food webs, and in energy/carbon cycling in marine

isotopes document seasonal changes in trophic nichesand winter foraging individual specialization in diving

predators from the Southern Ocean. J Anim Ecol 76: 826−836

Acknowledgements. The authors thank fieldworkers for col-

Stable isotopes reveal the trophic position and mesopela-

lecting diet samples, Paul Rodhouse for numerous discus-

gic fish diet of female southern elephant seals breeding

sions on the paper and on cephalopods in general, Janet Silk

on the Kerguelen Islands. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 370:

for creating Fig. 1, and Alexandra Baeta for stable isotope

analysis. The work at Crozet and Kerguelen was supported

financially and logistically by the Institut Polaire Français

(2009a) Tissue, ontogenic and sex-related differences in

Paul Emile Victor (Programme N°109, H. Weimerskirch)

δ13C and δ15N values of the oceanic squid Todarodes fil-

and the Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises, and at

ippovae (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae). Mar Biol 156:

South Georgia by the British Antarctic Survey. This work

was also supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tec-

nologia (FCT), the British Antarctic Survey and within

topes document the trophic structure of a deep-sea

research projects CEPH, POLAR, PROPOLAR and inter

cephalopod assemblage including giant octopod and

national programs ICED and SCAR AnT-ERA. This study

giant squid. Biol Lett 5: 364−367

represents a contribution to the Ecosystems component of

the British Antarctic Survey Polar Science for Planet Earth

(2013) A comprehensive isotopic investigation of habitat

Programme, funded by the Natural Environment Research

preferences in nonbreeding albatrosses from the South-

ern Ocean. Ecography 36: 277−286

Clarke MR (1977) Beaks, nets and numbers. Symp Zool Soc

Lond 38: 89−126

Clarke MR (1980) Cephalopoda in the diet of sperm whales

of the Southern Hemisphere and their bearing on sperm

whale biology. Discov Rep 37: 1−324

topic ratio as a recorder for surface ocean nitrate utiliza-

Clarke MR (1983) Cephalopod biomass:

tion. Global Biogeochem Cycles 8: 103−116

predation. In: Stone DM (ed) Memoirs of the National

Museum of Victoria, Vol 44. Museums Board of Victoria,

ald RA, Bearhop S (2010) Element patterns in albatrosses

Melbourne, p 95−107

and petrels: influence of trophic position, foraging range,

and prey type. Environ Pollut 158: 98−107

cephalopods. Adv Mar Biol 50: 191−265

diet of Weddell seals in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica as

levels of sharks. ICES J Mar Sci 56: 707−717

determined from scat collections and stable isotope

analysis. Polar Biol 19: 272−282

do albatrosses catch squid? Antarct Sci 6: 155−162

Guerreiro et al.: Isotope values of Southern Ocean cephalopods

Nesis KN (1987) Cephalopods of the world (translated by B.

Southern Ocean. Deep-Sea Res 29: 1−15

S. Levitov and edited by L. A. Burgess). T. F. H. Publica-

tions, Neptune City, NJ

tribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim Cosmo -

Park Y H, Gambéroni L, Charriaud E (1993) Frontal struc-

chim Acta 42: 495−506

ture, water masses, and circulation in the Crozet Basin.

J Geophys Res 98: 12361−12385

bution of nitrogen in animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta

partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much

variation. PLoS ONE 5: e9672

(2011) Assimilation of upwelled nitrate by small eukary-

otes in the Sargasso Sea. Nat Geosci 4: 717−722

composition and trophic levels of marine mammals. ICES

J Mar Sci 55: 467−481

bon and nitrogen isotope analysis reveals seasonal varia-

tion in the diet of leopard seals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 305:

(2010) Moving polewards in winter:

in the migratory strategy of a pelagic seabird? Front Zool

ine food webs using cephalopod beaks: new insight from

Rodhouse PG (1990) Cephalopod fauna of the Scotia Sea at

captively raised Sepia officinalis. Can J Zool 84: 766−770

South Georgia: potential for commercial exploitation and

possible consequences. In:

Kerry KR, Hempel G (eds)

trosses (Diomedea exulans L.) breeding at six circumpo-

Antarctic ecosystems:

ecological change and conser

lar localities. J R Soc N Z 22: 243−263

vation. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p 289−298

(2007) Applying new tools to cephalopod trophic dynam-

ecological niche of epipelagic fish in the Antarctic Polar

ics and ecology: perspectives from the Southern Ocean

Frontal Zone. Biol Bull 189: 77−80

Cephalopod Workshop, February 2–3, 2006. Rev Fish

Biol Fish 17: 79−99

the cephalopod Martialia hyadesi (Teuthoidea: Ommas-

trephidae) at the Antarctic Polar Front, Scotia Sea. Mar

paring isotopic niche widths among and within com

Biol 114: 415−421

munities: SIBER — Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R.

J Anim Ecol 80: 595−602

others (1996) Cephalopods and mesoscale oceanography

at the Antarctic Polar Front: satellite tracked predators

(2010) Seabird satellite tracking validates the use of lati-

locate pelagic trophic interactions. Mar Ecol Prog Ser

tudinal isoscapes to depict predators' foraging areas in

the Southern Ocean. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 24:

Roper CFE, Vecchione M (1997) In situ observations test

hypotheses of functional morphology in Mastigoteuthis

(Cephalopoda, Oegopsida). Bull Mar Sci 71: 893−901

ture of the marine food web at the Prince Edward Islands

Sackett WM, Eadie BJ, Exner ME (1974) Stable isotope com-

(Southern Ocean) determined by δ13C and δ15N analysis.

position of organic carbon in recent antarctic sediments.

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 208: 13−20

In: Tissot B, Bienner F (eds) Advances in organic chem-

istry 1973. Editions Technip, Paris, p 661–671

study of avian and mammalian trophic ecology. Can J

MA, Pond DW (2012) Food web dynamics in the Scotia

Sea in summer: A stable isotope study. Deep-Sea Res II

Richard P, Cherel Y (2011) Sequential isotopic signature

along gladius highlights contrasted individual foraging

strategies of jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas). PLoS ONE 6:

tion of the Antarctic Polar Frontal Zone to the north of

South Georgia in summer 1994. J Geophys Res 102:

Michener RH Kaufman L (2007) Stable isotope ratios as

tracers in marine food webs: an update. In: Michener RH,

Lajtha K (eds) Stable isotopes in ecology and en viron -

assimilation and export in naturally iron-fertilized waters

mental science. Blackwell publishing, Oxford, p 248−252

of the Southern Ocean from nitrogen, carbon and oxygen

Montoya JP (2007) Natural abundances of marine plank-

isotopes. Deep-Sea Res II 55: 820−840

tonic 15N. In: Michener RH, Lajtha K (eds) Stable iso-

Voss NA (1980) A generic revision of the Cranchiidae

topes in ecology and environmental science. Blackwell

(Cephalopoda; Oegopsida). Bull Mar Sci 30: 365−412

publishing, Oxford, UK, p 187−189

Voss NA, Nesis KN, Rodhouse PG (1998) The cephalopod

Nemoto T, Okiyama M, Takahashi M (1985) Aspects of the

Family Histioteuthidae (Oegopsida): systematics, biology,

roles of squid in food chains of marine Antarctic ecosys-

and biogeography. Smithson Contrib Zool 586: 293−372

tems. In: Siegfried R, Condy PR, Laws RM (eds) Antarctic

nutrient cycles and food webs. Springer-Verlag, Berlin,

13C abundances in the Antarctic Ocean with emphasis on

the biogeochemical structure of the food web. Deep-Sea

Nemoto T, Okiyama M, Iwasaki N, Kikuchi N (1988) Squid

Res 34: 829−841

as predators of krill (Euphausia superba) and prey for

Weimerskirch H, Salamolard M, Sarrazin F, Jouventin P

sperm whales in the Southern Ocean. In:

(1993) Foraging strategy of wandering albatrosses

(ed) Antarctic Ocean and resources variability. Springer-

through the breeding season:

a study using satellite

Verlag, Berlin, p 292−296

telemetry. Auk 110: 325−342

Mar Ecol Prog Ser 530: 119–134, 2015

Xavier JC, Cherel Y (2009) Cephalopod beak guide for the

ation in the cephalopod component of the diet of the

Southern Ocean. British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge

wandering albatross, Diomedea exulans, breeding at

Bird Island, South Georgia. Mar Biol 142: 611−622

do larger albatrosses eat bigger squid? J Zool (Lond) 271:

Rodhouse PG (2004) Foraging ecology and interactions

with fisheries of wandering albatrosses (

Diomedea exu-

Geographical Information System (GIS) atlas of cephalo-

lans) breeding at South Georgia. Fish Oceanogr 13:

pod distribution in the Southern Ocean. Antarct Sci 11:

effective method for assessing the proportions of cepha -

ing strategies and diets of breeding grey-headed and

lo pods in the diet of albatrosses. Auk 122: 1182−1190

wandering albatrosses at South Georgia. Mar Biol 143:

interactions of Antarctic seals as determined by stable

Xavier JC, Croxall JP, Trathan PN (2003b) Inter-annual vari-

isotope signatures. Polar Biol 27: 368−373

Editorial responsibility: Edward Durbin,

Submitted: January 10, 2014; Accepted: March 2, 2015

Narragansett, Rhode Island, USA

Proofs received from author(s): June 7, 2015

Source: http://www.cebc.cnrs.fr/publipdf/2015/GMEPS530_2015.pdf

For more information contact: Hunter Hackett or Ben Arens L.C. Williams & Associates (312) 565-3900 or (800) 837-7123 [email protected] or [email protected] [email protected] ‘SAWYER SAVES' OFFERS HOPE TO 900 MILLION PEOPLE WITH NO ACCESS TO CLEAN WATER New Initiative Enables Americans to Easily Get Involved To Help Remedy One of World's Greatest Problems

Phytochemistry 65 (2004) 865–873 Variation in pyrrolizidine alkaloid patterns of Senecio jacobaea Mirka Macel, Klaas Vrieling, Peter G.L. Klinkhamer Leiden University, Institute for Biology, Plant Ecology, PO Box 95162300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Received 30 July 2003; accepted 10 February 2004 We studied the variation in pyrrolizidine alkaloid (PA) patterns of lab-grown vegetative plants of 11 European Senecio jacobaea