Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Jemi.microbiology.ubc.ca

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

Deletion of the Escherichia coli K30 Group I Capsule

Biosynthesis Genes wza, wzb and wzc Confers Capsule-

Independent Resistance to Macrolide Antibiotics

Sandra Botros, Devon Mitchell, Clara Van Ommen

Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of British Columbia

The Escherichia coli capsule functions to protect bacterial cells from desiccation and environmental stresses. The E.

coli group I capsule is polymerized and transported to the surface of the cells through the action of the wza, wzb

and wzc gene products. It is thought that the presence of a capsule may confer a level of intrinsic antibiotic

resistance. Previous work exploring the role of capsule in antibiotic resistance showed inconsistent results between

different studies, and that the role of capsule in antibiotic resistance may be dependent on antibiotic class. In this

study we sought to examine the role of the E. coli K30 group I capsule in antibiotic resistance across ten different

antibiotic classes. We examined the E. coli K30 strain CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] that has a chromosomal deletion

of three key capsule biosynthesis genes (wza, wzb and wzc) and its isogenic parental strain E69. We quantified the

capsule production of both strains and compared the susceptibility of the strains to ten different antibiotics. In

doing so, we identified macrolide antibiotics as a class of interest and further examined the susceptibility of the

strains to additional macrolides and a ketolide. We observed that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] exhibited diminished

production of capsular polysaccharides compared to E69 at 21°C, but that both strains produced comparably low

amounts of capsule at 37°C. Contrary to past work on other antibiotic classes, we observed that CWG655Δ[wza-

wzb-wzcK30] was more resistant to macrolide antibiotics, but not ketolides, when compared to E69 at both 21°C and

37°C. From this study, we conclude that a deletion of the capsule biosynthesis genes wza, wzb and wzc confers

resistance to the macrolide family of antibiotics in a mechanism independent of capsule production.

Capsular polysaccharides (CPS) are synthesized,

kanamycin resistance (7) and Song

et. al. reported that

transported and anchored to the surface of the cell by many

capsule could interact with tetracycline, providing

bacterial species, forming a hydrated layer around the cell

resistance via an unknown mechanism (8). Conversely,

that protects it from desiccation and environmental stress

Parmar

et. al found that the capsule did not confer

(1). The

Escherichia coli K30 group I capsule is assembled

resistance to kanamycin or tetracycline, while Drayson

et.

via the Wyz-dependent biosynthesis system, and

al concluded that antibiotic resistance following exposure

polymerized and transported via the action of the Wza,

to sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations was conferred in

Wzb and Wzc proteins (3). Wza is found in the outer

a capsule-independent fashion (9, 10). It has been

membrane and polymerizes to form a channel through

suggested by several groups that capsule involvement in

which the CPS is translocated (2). Wzc is an integral

antibiotic resistance is antibiotic class specific, which may

membrane protein of the inner membrane, and participates

explain, in part, the varied and contradictory results seen in

in the polymerization of CPS through its tyrosine

previous work (6-10).

autokinase activity. Wzb is found in the cytoplasm and is

Each of the many classes of antibiotics has a unique size,

the cognate phosphatase of Wzc. (2). Whitfield

et. al.

structure and bacterial target (11). The macrolide family is

developed an

E. coli K30 group I mutant strain,

characterized by the presence of a large 14, 15, or 16-

CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30], that has a chromosomal

membered lactone ring and attached sugar groups (12).

deletion of the

wza,

wzb and

wzc genes resulting in a

Different macrolides vary in ring size and in the chemical

mutant that exhibits decreased surface assembly of group I

groups attached to the ring or sugar moieties (12).

CPS when compared to the isogenic parental strain E69

Macrolides of interest in this study include erythromycin, a

common representative macrolide, as well as its

Previous work suggests that the barrier function of the

capsule may confer a level of antibiotic resistance by

Additionally, a new sub-group of macrolides called

inhibiting access of the antibiotics to the cell (4,5). These

ketolides has been recently developed that includes the

studies have demonstrated that exposure of

E. coli strains

antibiotic telithromycin (12).

to sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics results in an

Macrolides act by binding to the 50s subunit of the

increase in CPS production and a corresponding increase

bacterial ribosome at the 23s rRNA and inhibit protein

in antibiotic resistance (4). However, there has been

synthesis by inducing dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA (13).

conflicting evidence surrounding the direct role of capsule

Four main mechanisms of macrolide resistance have been

in mediating antibiotic resistance. For example, Ganal

et.

previously observed. Firstly, the outer membrane of many

al. reported resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin in a

Gram-negative bacteria can confer resistance (14). For

capsule-dependent fashion (6). In addition, Al Zharani

et.

example, mutations that impair the barrier function of the

al. found that the

E. coli capsule was necessary for

outer membrane were found to increase susceptibility to

Page

1 of

8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

azithromycin, clarithromycin and roxithromycin (15).

al. (16), with slight modifications. A colony of each cell type was

Secondly, modification of the antibiotic target through

inoculated in 5 ml of either LB or MH media and grown

methylation of the 23s rRNA can confer resistance (14).

overnight at either 21oC or 37oC. We conducted experiments

Thirdly, resistance can be conferred through an efflux

using both LB and MH media because past work by Parmar

et. al. identified differences in the production of capsular polysaccharide

pump (14). Lastly, macrolides can be inactivated by

between strains grown in LB and MH media (9). The following

enzymatic activity in the cell, including that of esterases

day, optical density readings at 660nm for each culture were

and phosphotransferases (14).

measured using a Spectronic 20+ spectrophotometer, and 1 ml of

Given the conflicting evidence surrounding the role of

the same culture was transferred into a sterile microcentrifuge

capsule polysaccharides in antibiotic resistance, we

tube. Next, the 1ml samples were centrifuged using an Eppendorf

examined the role of capsule production on antibiotic

5415D microcentrifuge for 2.5 minutes at 16,100 x g. The

resistance to a range of antibiotics. We examined the

E.

supernatants were discarded and the pellets were washed 3 times

coli K30 group I mutant strain CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-

with 1ml of 50 mM NaCl. Next, the pellets were re-suspended in 1ml of 50 mM EDTA. The samples were then incubated at 37oC

wzcK30] in addition to its wild type (WT) parental strain

on a shaker for 30min. After incubation, the samples were

E69 (3). We quantified the capsule production of both

pelleted at 16,100 x g and the supernatant containing capsular

strains and compared the susceptibility of the two strains to

polysaccharides was transferred into a sterile microcentrifuge

ten different classes of antibiotics. From this, we identified

tube. The subsequent capsule quantification was performed with

macrolides as a class of interest and further examined the

the phenol-sulphuric acid assay (16). A 1.0 mg/ml carbohydrate

susceptibility of the strains to additional macrolides and a

stock solution containing 0.05% w/v sucrose and 0.05% w/v

ketolide. By examining different macrolide antibiotics as

fructose was used to prepare the standard curve. For capsule

well as a ketolide, we were able to determine if patterns of

quantification, 400 uL of supernatant was combined with 400 uL

antibiotic susceptibility or resistance were specific to an

of 5% phenol and 2 mL of 93% sulphuric acid in a glass test tube. Colour was allowed to develop for 10 min and the absorbance

individual antibiotic or if they applied to the larger

was measured at 490nm on a Spectronic 20+ spectrophotometer.

antibiotic class.

Each experiment was done in replicates of three.

We observed that CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30] produced

Capsule Staining. A colony of each cell type was streaked onto

diminished capsule compared to the WT and showed

either LB or MH solid media and grown overnight at either 21oC

increased resistance to macrolide antibiotics. Overall, our

or 37oC. Colonies were taken from the plates using a sterilized

results suggest that, for macrolide antibiotics, the

E. coli

loop and suspended in 250uL of sterile saline. Capsule staining

K30 group I capsule does not play a role in antibiotic

was performed using a modified version of the Maneval's capsule

resistance, and that CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzc

staining method described by Hughes and Smith (17). First, the

cell suspension in sterile saline was mixed with 250µL of Congo

resistant to macrolides via a mechanism independent of

Red (1% aqueous solution, Sigma Chemical Company C-6767),

capsule but related to the absence of the

wza, wzb and

wzc

spread onto a glass microscope slide using a sterilized loop, and

air-dried for 5-10 minutes. Next, 150µL of Maneval's solution

was then pipetted onto the dried smears (0.047% w/v acid

MATERIALS AND METHODS

fuchsin, JT Baker Chemicals, A355-3; 2.8% w/v ferric chloride,

Bacterial Strains, Preparation of Media and Growth

Fisher Scientific I-89; 4.8% v/v aqueous glacial acetic acid,

Conditions. E. coli K30 strains E69 (serotype: O9a:K30:H12)

Acros, 42322-0025; 3.6% v/v aqueous phenol solution, Invitrogen

and CWG655 [

wza

IS509-037) and allowed to sit for approximately 2 minutes. The

22 min::

aadA Δ(

wza-wzb-wzc) K30::

aphA3 Kmr

Spr] were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Chris Whitfield

counterstain was washed off with dH2O and the slides were air-

(Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of

dried before being viewed using a light microscope at 1000x

magnification with oil immersion

K30] has a polar

aadA insertion

in the

wza locus corresponding to 22 minutes on the

E. coli K12

Disc Diffusion Assay. Disc diffusion assays were performed

lineage map that eliminates expression of this copy of the

wza-

using a modified version of the Kirby-Bauer method (18). Strains

wzb-wzc locus (3). The second locus of

wza-wzb-wzc was

were grown overnight in liquid culture of LB or MH media at

inactivated using PCR amplification and cloning into the suicide

21°C or 37°C. The optical density of the cultures was measured at

vector pWQ173, which was used to excise parts of

wza and

wzc

660nm using a Spectronic 20+ spectrophotometer and the cultures

as well as all of

wzb (3). In this paper, strain CWG655 is referred

were then diluted with sterile broth to 1 optical density unit. LB

to as either CWG655 Δ[

wza-wzb-wzc]

or MH plates were spread plated with 100µL of the diluted liquid

K30 or as "mutant strain"

while E69 is denoted as "wild type" (WT). All experiments were

cultures. Antibiotic discs (7mm diameter) prepared with either

performed at either 21°C or 37°C. Liquid cultures were incubated

sulfamethoxazole,

on a shaker contained in either a 37°C walk-in incubator or at

polymyxin, vancomycin, erythromycin, tetracycline, gentamycin,

room temperature (approximately 21°C). Plates were incubated in

or norfloxacin (AB-biodisk) obtained from the Department of

either a 37°C walk-in incubator or at room temperature

Microbiology and Immunology at UBC were placed onto the

(approximately 21°C). Bacterial cells were grown in either Luria

plates using sterilized forceps. For the roxithromycin,

Bertani (LB) broth (1.0% w/v tryptone, 0.5% w/v yeast extract,

clarithromycin, and telithromycin disc diffusions, stock solutions

0.5% w/v NaCl, pH 7) or Mueller Hinton (MH) broth (0.2% w/v

of 10mg/mL roxithromycin, clarithromycin and telithromycin

beef extract, 1.75% w/v acid digest of casein, 0.15% starch, pH

were obtained from the lab of Dr. Charles Thompson

7.3, not cation-adjusted) for capsule isolation as well as capsule

(Department of Microbiology and Immunology, UBC) and 10µL

staining. For other capsule staining experiments, as well as for the

of each solution was pipetted onto blank discs. Each experiment

disc-diffusion assay, bacterial cells were grown on plates made

was done is replicates of three, with three or four discs per plate.

from either LB (1.5% agar) or MH (1.7% agar) media.

The plates were incubated for 18 hours at either 21°C or 37°C

Capsule Extraction and Quantification. Capsule extraction

depending on the initial incubation temperature of the liquid

and quantification was performed as outlined by Brimacombe

et

culture, and the diameters of the zones of inhibition were

Page

2 of

8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

measured in millimetres. An increase in the diameter of the zone of inhibition indicates increased susceptibility and a decrease in the size of the zone of inhibition indicates increased resistance.

Statistical Analysis. Statistical analysis was performed for the

disc diffusion assay as well as for the phenol-sulphuric acid assay. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired, two tailed t-test (p<0.5). For the phenol-sulphuric acid assay, comparisons were made between CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30] and the WT strain, at both 21oC and 37oC for LB and MH media. Comparisons were also made between 21°C and 37°C for the WT and CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30]. For the disc diffusion assay, comparisons were made between CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30] and the WT strain, at both 21oC and 37oC for LB and MH media.

Deletion of the wza-wzb-wzc genes decreases capsule

production at 21°C but not at 37°C compared to the

WT strain. To confirm decreased capsule biosynthesis

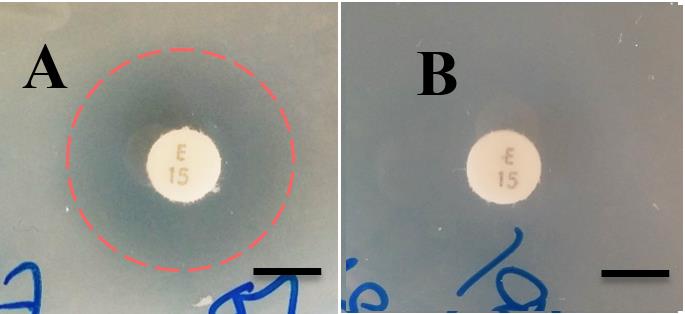

FIG 1 Differences in capsular polysaccharide produced by the

WT strain and CWG655Δ[

ability of CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30] using the phenol-

wza-wzb-wzcK30] compared to the

sulphuric acid capsule quantification method. Strains were

WT strain, we quantified capsular polysaccharide

cultured overnight in 21°C or 37°C shaking incubators in LB liquid

production of both strains at 21°C and 37°C using the

media, and capsule polysaccharide was extracted and quantified using

phenol-sulphuric acid assay. Given that past groups have

the phenol-sulphuric acid assay. * indicates p<0.05, n.s. indicates not

observed decreased capsule production at 37°C, compared

to 21°C, we decided to conduct our analysis at both

culture, this experiment confirmed that differences in

temperatures (9). We expected that CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-

capsule production between the strains were also observed

wzcK30] would produce less capsular polysaccharide

on solid media. Based on the phenol-sulphuric acid assay

compared to the WT and that both strains would produce

results (Fig. 1), we expected that the WT cells would have

more capsular polysaccharide at 21°C, compared to 37°C.

a larger visible capsule than the CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-

At 21°C, the WT strain exhibited 14-times greater

production of capsular polysaccharide compared to

K30] cells at 21°C, but not 37°C. Resulting images of

stained WT cells (Fig. 2A) and CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-

wza-wzb-wzcK30] when grown in LB broth

(Fig. 1). At 37°C, we found no significant difference in

K30] cells (Fig. 2B) grown at 21°C showed increased

capsule size visible around the WT cells, and not the

capsular polysaccharide production for the WT compared to CWG655Δ[

K30] cells. Both WT (Fig. 2C)

K30] (Fig. 1). Additionally, we

cells and CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzc

observed 12-times greater production of capsular

comparable capsule size at 37°C (Fig. 2D). However, we

polysaccharide for the WT strain at 21°C compared to

observed only minor differences in capsule size between

37°C (Fig. 1). We did not observe a significant difference in capsular polysaccharide production for CWG655Δ[

WT cells grown at 21°C and 37°C (Fig. 2A, 2C). These

results are unexpected given that we observed that the WT

wzb-wzcK30] between 21°C and 37°C (Fig.1). We

produced more capsular polysaccharides at 21°C,

replicated these experiments using both strains grown in

compared to 37°C (Fig. 1). We suspect that our inability to

MH broth and observed a similar trend in which the WT

detect large differences in capsule size is due to disparate

microscope image quality. Despite our inability to detect

wza-wzb-wzcK30] (Supplemental Fig. 1). When

large difference in capsule size between WT cells grown at

grown in MH media we observed a less pronounced

21°C and 37°C, from these results we conclude that, when

difference in polysaccharide production between the two

grown on solid media, CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzc

strains at 21°C, indicating that LB would be a more

decreased capsule size compared to the WT at 21°C, and

suitable media for further study regarding the effects of the

wza-wzb-wzc gene deletion on antibiotic resistance. From

K30] and the WT show similar

capsule sizes at 37°C.

these results, we conclude that the WT strain produces more capsular polysaccharide than CWG655Δ[

exhibits

increased

resistance to erythromycin compared to the WT strain.

wzcK30] at 21°C, but not 37°C.

Due to the increase in capsule production observed for the

WT cells exhibit increased capsule thickness

compared to CWG655Δ[

WT strain compared to CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzc

K30] on solid LB

21°C, we hypothesized that an increase in capsular

agar. To further confirm that CWG655Δ[

wza-wzb-wzcK30]

polysaccharides might influence antibiotic resistance in a

was deficient in capsule compared to the WT, we performed capsule staining using Maneval's staining

class-dependent manner. In addition, differences in antibiotic susceptibility between the WT strain and

procedure, and visualized capsule size using light

microscopy. Given that the antibiotic disc diffusion

K30] were predicted to be more

prominent at 21°C when compared to 37°C, due to the lack

experiments were to be performed on solid media but the

of differential capsule production between the strains

phenol-sulphuric acid assay used cells grown in liquid

Page

3 of

8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

We observed no significant differences in capsule

production at 37°C between CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30]

and the WT strain (Fig. 1). However, we observed

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] and the WT strain at 37°C (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the differential susceptibility of the strains to erythromycin may not be

due to the physical presence of capsule. From this we

conclude that although the deletion of the wza-wzb-wzc

capsule biosynthesis genes confers increased resistance to

erythromycin, this effect may not be due to decreased capsule production.

Resistance

erythromycin extends to the macrolides clarithromycin

and

ketolide

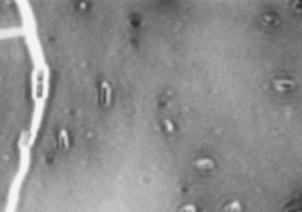

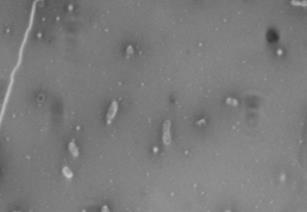

FIG 2 Differences in capsule thickness of WT and

telithromycin. We observed differences in antibiotic

susceptibility between the WT strain and CWG655Δ[wza-

K30] cells grown on solid LB agar media at

21°C and 37°C. (A) E69 WT cells grown on LB agar at 21°C; (B)

wzb-wzcK30] that varied with antibiotic class (Supplemental

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] cells grown on LB agar at 21°C. (C) E69

Fig. 2). Additionally, we observed that CWG655Δ[wza-

WT cells grown on LB agar at 37°C. (D) CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30]

wzb-wzcK30] exhibited increased resistance to erythromycin

cells grown on LB agar at 37°C. Strains were grown overnight on LB agar plates at 21°C, and cell capsules were stained using Maneval's

compared to the WT (Fig. 3). In order to determine if the

staining protocol and visualized at 1000x magnification. Grey regions

resistance conferred by the wza-wzb-wzc gene deletion was

indicate cell bodies, and white regions indicate capsule.

specific to erythromycin or if it also applied to other

antibiotics in the macrolide class, we conducted further

observed at 37°C (Fig. 1). To test our hypothesis we

conducted a screen of ten antibiotics, each of a different

roxithromycin. Additionally, we used telithromycin, which

antibiotic class, using an antibiotic disc diffusion assay on

is a member of the macrolide sub-group the ketolides. We

LB and MH agar media for both strains at 21°C and 37°C.

examined the susceptibilities of the WT strain and

We observed that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] exhibited

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] at both 21°C and 37°C. At

decreased resistance to some antibiotics, such as

21°C, disc diffusion results showed a 3-fold increase in

nitrofurantoin, yet no consistent trends in resistance

susceptibility to roxithromycin for the WT strain compared

changes to many other antibiotics, when compared to the

to CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30]. A similar trend of

WT (Supplemental Fig. 2). However, we also observed

increased susceptibility of the WT strain was seen for

that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] exhibited increased

clarithromycin, but these results were not significant at

resistance to some antibiotics when compared to the WT,

21°C. (Fig 4). When grown at 37°C, we observed at 10-

such as erythromycin and tetracycline (Supplemental Fig.

fold increase in susceptibility to roxithromycin for the WT

2). These results suggest that a deletion of the wza-wzb-

compared to CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] (Fig. 4).

wzc genes can increase, decrease, or have no effect on

Similarly, we observed that the WT was susceptible to

resistance to antibiotics, depending on the antibiotic tested.

clarithromycin with a clear zone of inhibition around the

Based on the observed results, we identified erythromycin

antibiotic disc, while CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] was

as an antibiotic of interest for further study. At 37°C, the

resistant with growth up to the edge of the antibiotic disc.

WT strain had some degree of susceptibility to

At both temperatures, we observed that the WT and

erythromycin, as indicated by the presence of a zone of

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] were comparably resistant to

the ketolide, telithromycin (Fig. 4). We observed a similar

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] showed no susceptibility,

trend in results when disc diffusion assays were replicated

growing consistently up to the edge of the disc (Fig. 3A).

on MH media (Supplemental Fig. 4). From these results

The zones of inhibition surrounding the erythromycin discs

we conclude that the wza-wzb-wzc gene deletion confers

appeared as a gradient, not a distinct line (Fig. 3A).

increased resistance to the macrolides clarithromycin and

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] showed a significant increase

roxithromycin, similar to the pattern seen in erythromycin,

in resistance to the erythromycin compared to the WT

but this does not extend to the ketolide telithromycin. This

strain (Fig. 3B). We observed a similar pattern at 21°C, but

effect is independent of physical capsule presence.

at this temperature results did not reach significance (Fig.

3B). Additionally, we obtained similar results with a disc

DISCUSSION

diffusion assay performed on MH agar, where

In this study, comparison of capsule production

between the WT strain and CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-

increased erythromycin resistance at 37°C and a similar

but less pronounced result at 21°C compared to the WT

revealed that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30]

exhibited 14-times less CPS production than the WT

strain (Supplemental Fig. 3).

strain at 21°C . This is consistent with the expected

Page 4 of 8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

results, due to the chromosomal deletion of the capsule biosynthesis genes wza, wzb and wzc, as described by Whitfield et al. (3). Our results are consistent with the findings of Parmar et al., who examined a strain deficient in only the Wza channel-forming protein necessary for capsule assembly, and demonstrated decreased CPS production by that mutant strain (9).

We observed a greater difference in capsule

production between the WT strain and CWG655Δ[wza-

wzb-wzcK30] at 21°C than at 37°C, and an overall

increase in capsule production at 21°C for the WT (Fig.

1). Although the group I E. coli capsule was not previously thought to be thermoregulated (2), studies by

Parmar et. al., Drayson et. al, and Stout et. al., and have reported increased capsule production at 21°C compared to 37°C (9, 10, 19). This observation is of interest because some previous studies that have failed to find differences in antibiotic resistance based on the presence or absence of capsule carried out experiments at only 37°C (20). For example, Naimi et. al. examined the role of capsule in streptomycin susceptibility with organisms grown at 37°C and observed no difference in susceptibility between a wza mutant and its isogenic WT strain (20). A possible explanation for their result is

that the strains were producing comparable levels of

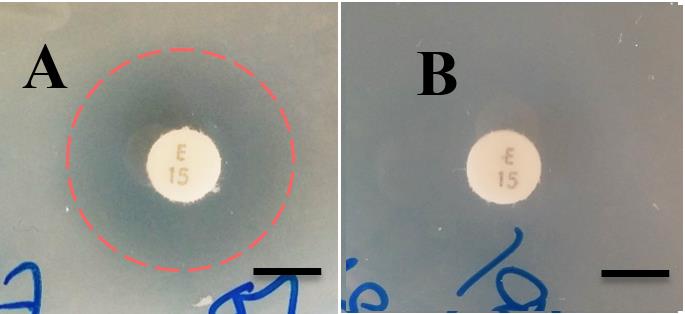

FIG 3 Susceptibility of CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] and the WT

strain to erythromycin via disc diffusion assay. (A, B)

polysaccharides at 37°C. However, other studies have

Representative disc diffusion results showing that the WT is

examined the same strains at both 21°C and 37°C and

susceptible to erythromycin, as seen by a zone of clearance around the

also failed to find differences in antibiotic resistance to

erythromycin disc indicated by a red dashed circle. CWG655Δ[wza-

streptomycin between WT and capsule deficient

wzb-wzcK30] is shown to be resistant to erythromycin, as seen by the

mutants (9, 10). The previous findings on the topic of

lack of inhibition around the erythromycin disc. Scale bars = 7mm; (C) Differences in susceptibility of the WT and CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-

capsule-dependent

wzcK30] to erythromycin at 21°C and 37°C. Disc diffusion assays were

contradictory, however, as there have been other groups

carried out using antibiotic discs on LB agar plates. An increase in the

that have suggested a link between capsule production

diameter of the zone of inhibition indicates an increase in

and resistance to certain antibiotics, such as kanamycin,

susceptibility. * indicates p<0.05, n.s. indicates non-significant. Dashed line indicates diameter of antibiotic disc.

tetracycline, and streptomycin (4, 7, 8). Therefore, we

suggest that capsule may influence antibiotic resistance

compared to the WT strain (Supplementary Fig. 2). Our

for specific classes of antibiotics.

results indicate that our understanding of the role of

In this study, we used a screen of ten different

capsule in antibiotic resistance should be modified to

antibiotics to compare the susceptibilities of the WT

suggest that an increase in capsule production can either

strain and CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] using the disc

increase, decrease or have no effect on antibiotic

diffusion assay for antibiotic resistance. Due to the

resistance depending upon the antibiotic class being

limited number of replicates we performed, the majority

of antibiotics tested showed no significant difference in

Due to the increase in resistance observed by

susceptibility between the two strains (Supplementary

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] to erythromycin, we

Fig. 2). Indeed, at 21°C we noticed no significant

decided to further investigate macrolides as our

differences between the antibiotic susceptibilities of

antibiotic family of focus. In this study, we

either strain for any of the antibiotics tested.

demonstrated that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] showed

Nonetheless, the general trend supports the observation

increased resistance to the macrolide antibiotics

in the literature that the presence of an intact capsule

erythromycin, clarithromycin, and roxithromycin, but

can increase resistance to a variety of antibiotics (4, 7,

not the ketolide antibiotic telithromycin, when

8), or have no effect (9, 10). However, we also

compared to the WT strain (Fig. 3, 4). We observed

identified another possibility: the absence of wza, wzb,

comparable results at 21°C and 37°C. However,

and wzc in our mutant may increase antibiotic

differences in susceptibility to erythromycin and

clairithromycin between the WT and CWG655Δ[wza-

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] exhibited an increase in

wzb-wzcK30] only reached significance at 37°C (Fig. 3,

resistance to both tetracycline and erythromycin

4). We also observed that there were no significant

Page 5 of 8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

increased resistance observed in CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] in the context of OM permeability. Whitfield et. al. observed that the CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] strain shows depleted surface assembly of CPS (3). These results were replicated in this study (Fig.1, 2). Whitfield et. al. also observed that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] produces capsular oligosaccharides with a low degree of polymerization that are attached to the lipid A moiety of LPS and form an alternate glycoform of LPS called K-LPS (3). We speculate that the increased resistance to macrolides exhibited by CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] to macrolides may be related to the formation of K-LPS, and therefore an altered OM structure and permeability (C. Whitfield, personal correspondence).

This notion is supported by previous studies that have

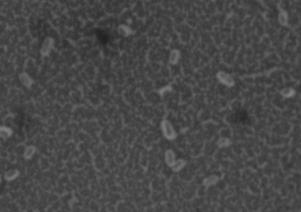

FIG 4 Differences in susceptibility of the WT strain and

CWG655Δ[

found that modifications in OM permeability alter

wza-wzb-wzcK30] to the macrolides clarithromycin,

roxithromycin, and the ketolide telithromycin at 21°C and 37°C.

macrolide susceptibility. Vaara found that mutations

Disc diffusion assays were carried out on LB agar plates. An increase

that affected OM structure and increased permeability,

in the diameter of the zone of inhibition indicates an increase in

such as mutations in lipid A synthesis in E. coli,

susceptibility. * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p<0.005, n.s. indicates

decreased the MICs of erythromycin, roxithromycin,

non-significant. Dashed line indicates diameter of antibiotic disc.

clarithromycin and azithromycin (23). Similarly, Buyuk

differences in CPS production at 37°C between the WT

et. al. found that certain strains of Pseudomonas

aeruginosa are more susceptible to macrolides due to

together these results suggest that the presence or

increased membrane permeability (45). Finally, Farmer

absence of capsule does not play a role in antibiotic

et. al observed that the MIC of azithromycin was

resistance to macrolides for these strains, but that the

increased 8 times with the addition of a magnesium

absence of the wza, wzb and wzc genes may play a role

supplementation that decreased membrane permeability

in the increase in resistance of CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-

(25). These previous findings lend support to our

proposed model wherein the wza-wzb-wzc deletion

These results are consistent with past

observations made by Drayson et. al which suggested

confers macrolide resistance through an alteration of the

that antibiotic resistance can be conferred in a capsule-

OM structure that causes changes in OM permeability.

independent fashion (10). Given that our data suggest

The last observation of significance in this study is

that the absence of wza, wzb and wzc increases

that both the WT strain and CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-

antibiotic resistance in a capsule-independent manner, a

wzcK30] exhibited comparable levels of resistance to

discussion of the potential mechanisms of resistance

telithromycin, with but differing levels of susceptibility

to macrolides that were close derivatives of

A variety of mechanisms for resistance to macrolides

erythromycin (Fig. 3, 4). Different macrolide antibiotics

have been observed (21). Given that capsule is

vary in chemical components that are attached to the

associated with the outer membrane (OM) and wza, wzb

lactone ring or sugar moieties (11). Clarithromycin is

and wzc, are involved in capsule assembly we suggest

derived from erythromycin by substituting a methoxy

that the mechanism of most relevance to this study is

group for the C-6 hydroxyl group of erythromycin (26),

the role of the OM as a permeability barrier. Typically,

while roxithromycin has an N-oxime side chain

macrolide antibiotics are used to treat Gram-positive

attached to the lactone ring (27). Telithromycin is a

infections because the OM of Gram-negative bacteria

member of a macrolide derivative family called

can confer a level of resistance that makes clinical use

ketolides, which have a further modified structure from

of macrolides, particularly erythromycin, challenging

typical macrolides in that a keto functional group is

for those types of infections (22). This is thought to be

substituted for the sugar moiety at C-3 on the lactone

due to the hydrophobic nature of the macrolides, which

ring (26). A methoxy group replaces the hydroxyl group

can prevent them from passing the charged lipid A

at C-6 and C-11-12 is cyclized to make a carbamate

component of LPS present in the OM (22).

group with an imidazo-pyridyl group attachment (26).

Because our mutant strain lacks three genes and their

We suggest that the difference we see in susceptibility

corresponding protein products, we cannot identify a

may be due to structural differences between

single gene product that, when absent, confers the

telithromycin and the macrolides. Most literature in this

area suggests that ketolides have increased activity

developed a model as a potential explanation for the

macrolides; however, limited data is available regarding

Page 6 of 8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

mechanisms of resistance to ketolides (26). Recent

work could also focus on elucidating the mechanism of

work has reported that few bacterial strains exhibit

resistance to telithromycin used by both E69 and

telithromycin resistance (26). In the literature, it appears

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30]. Given that the incidence of

that those strains that are resistant to ketolides exhibit

telithromycin is rare, future studies could attempt to

their resistance through mechanisms that are common

explain the observed resistance. For example, the strains

to those for macrolide resistance. Walsh et al. reported

could be examined in an attempt to determine if they

two mechanisms of telithromycin resistance: target

harbour genes that have been identified in the literature as

modification by methylation of the 23s rRNA by the

being involved in telithromycin resistance (28).

We observed that the WT strain produced 12-times

erm(B) methylase gene or efflux mediated by the

greater levels of capsular polysaccharides at 21°C

mef(B) gene (28). With our limited data we cannot

compared to 37°C. Past publications have reported similar

develop any conclusive hypotheses regarding the source

results (9). Given that group I capsule production is not

known to be thermoregulated (2), future work could

examine the potential mechanisms behind these results by

mechanisms include exclusion due to its size or charge,

examining the expression of genes involved in capsule

or the presence of any of the resistance mediating genes

assembly at 21°C and 37°C.

described above.

Finally, future experiments could be conducted to further

In this study our aim was to examine the

examine the other observed results in our antibiotic screen.

CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzcK30] mutant strain and its WT

That is, higher replicate screens could, and should, be

parental strain E69, with particular focus on the role of

conducted in order to determine the significance of

the K30 group I capsule in antibiotic resistance to

observed trends, and to further confirm the results

multiple antibiotic families. We observed that

observed herein. Moreover, certain antibiotics could be

further studied in order to aid in the explanation of the

K30] produced less capsular

polysaccharide than the WT at 21°C, but not 37°C. We

results. For example, tetracycline resistance was increased

also observed that CWG655Δ[wza-wzb-wzc

in the absence of capsule in this study and further work

increased resistance to macrolides, but not the ketolide

could focus on elucidating this mechanism. Additionally,

subgroup, when compared to the WT at 21°C and 37°C.

for norfloxacin at 21°C the WT strain showed increased resistance compared to CWG655Δ[

Taken together, our data suggest that a deletion of the

wza-wzb-wzcK30], but

this result was reversed at 37°C. Future work could focus

wza, wzb and wzc genes confers resistance to macrolide,

on attempting to replicate this result and examine the

but not ketolide, antibiotics via a capsule-independent

mechanism behind it. Indeed, these are but two of several

mechanism. Overall, we conclude that the absence of

examples of antibiotics that could be further studied in

the capsule biosynthesis genes wza, wzb and wzc

relation to the role of capsule in antibiotic resistance.

confers increased resistance to macrolide antibiotics.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

We would like to thank the Department of Microbiology and

Although we have indicated that the absence the wza, wzb,

Immunology at the University of British Columbia for their

and wzc genes is important for macrolide resistance, and

funding and support. We would like the thank Dr. David Oliver,

that this phenomenon is capsule-independent, the

Jia Wang and Céline Michaels, for their guidance, instruction,

mechanism of resistance remains unknown. The clearest

and support, as well as the staff of the media room for providing

and most pressing direction to be taken from this study is

us with equipment and supplies. In addition, we would like to

an examination of the effect of single gene mutations in

thank the Department of Pharmacology at UBC for gifting the

wza, wzb or wzc on resistance to macrolide family

Department of Microbiology with many of the antibiotic disks used in our experiments. Further, we would like to thank Dr.

antibiotics. Since this study was conducted using a mutant

Chris Whitfield at the University of Guelph for providing the E.

with a deletion of all three of these capsule assembly

coli strains and for his valuable insight into our work. Finally we

genes, a causal relationship cannot be established between

would like Dr. Charles Thompson at the University of British

the absence of any one gene (or a combination) and the

Columbia for providing us with the macrolide antibiotics used in

observed increase in resistance to macrolides. Further

our experiments.

study is warranted to determine whether or not the

observed effect can be traced to a single gene product, or

REFERENCES

whether the effect is the result of a combination of

1. Reid, AN, Szymanski, CM. 2010. Biosynthesis and assembly of

deletions. Additionally, the effect of other outer membrane

capsular polysaccharides-Chapter 20, p. 351-373. In Moran, A

genes could be studied in order to determine whether this

(ed), Microbial Glycobiology: Structure, Relevance and Application. Elsevier Inc, London, UK.

phenomenon is unique to the capsule biosynthesis genes

2. Whitfield, C. 2006. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular

wza, wzb and wzc or whether deletions in other membrane

polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:39-

channels, kinases, etc. are sufficient to induce the

observed, macrolide-resistant phenotype.

3. Reid, AN, Whitfield, C. 2005. Functional analysis of conserved

We observed that the WT strain and CWG655Δ[wza-

gene products involved in assembly of Escherichia coli capsules and exopolysaccharides: evidence for molecular recognition

wzb-wzcK30] exhibited telithromycin resistance. Future

Page 7 of 8

Journal of Experimental Microbiology and Immunology (JEMI)

Copyright April 2015, M&I UBC

between Wza and Wzc for colanic acid biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol.

17. Hughes RB, Smith, A. 2011. Capsule stain protocols. ML

Microbe Library, ASM. Accessed on 9th March 2015 at

4. Lu, E, Trinh, T, Tsang, T, Yeung, J. 2008. Effect of growth in

sublethal levels of kanamycin and streptomycin on capsular

18. Hudzicki, J. 2009. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test

Escherichia coli B23. J. Exp. Microbiol. Immunol. 12:21-26.

protocol. ML Microbe Library, ASM. Accessed on 8th February

5. Slack, MP, Nichols, WW. 1982. Antibiotic penetration through

bacterial capsules and exopolysaccharides. J. Antimicrob.

Chemother. 10:368-372.

6. Ganal, S, Guadin, C, Roensch, K, Tran, M. 2007. Effects of

19. Stout, V, Gottesman, S. 1990. RcsB and RcsC: a two-

streptomycin and kanamycin on the production of capsular

component regulator of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli. J.

polysaccharides in Escherichia coli B23 cells. J. Exp. Microbiol.

Bacteriol. 172:659-669.

Immunol. 11:54-99.

20. Naimi, I, Nazer, M, Ong, L, Thong, E. 2009. The role of wza in

7. Al Zahrani, F, Huang, M, Lam, B, Vafaei, R. 2013. Capsule

extracellular capsular polysaccharide levels during exposure to

formation is necessary for kanamycin tolerance in Escherichia

sublethal doses of streptomycin. J. Exp. Microbiol. Immunol.

coli K-12. J. Exp. Microbiol. Immunol. 17:24-28.

Vol. 13:36-40.

8. Song, C, Sun, XF, Xing, SF, Xia, PF, Shi, YJ, Wang, SG.

21. Leclercq, R. 2002. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and

2013. Characterization of the interactions between tetracycline

lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical

antibiotics and microbial extracellular polymeric substances with

implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:482-492.

spectroscopic approaches. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 21:

22. Poole, K. 2002. Outer membranes and efflux: the path to

multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Pharm.

9. Parmar, S, Rajwani, A, Sekhon, S, Suri, K. 2014. The

Biotechnol. 3:77-98.

Escherichia coli K12 capsule does not confer resistance to either

23. Vaara, M. 1993. Outer membrane permeability barrier to

tetracycline or streptomycin. J. Exp. Microbiol. Immunol.18:76-

azithromycin, clarithromycin, and roxithromycin in gram-

negative enteric bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

10. Drayson R, Leggat T, Wood M. 2011. Increased antibiotic

37:354-356.

resistance post-exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations is

24. Buyck, J, Tulkens, PM, Van Bambeke, F. 2011. Increased

independent of capsular polysaccharide in Escherichia coli. J.

susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to macrolides in

Exp. Microbiol. Immunol. 15:36-42.

biologically-relevant media by modulation of outer membrane

11. Walsh, C. 2003. Antibiotics: actions, origins, resistance.

permeability and of efflux pump expression, p. 17-20. In

American Society for Microbiology (ASM).

Anonymous 51st Interscience conference on antimicrobial agents

12. Omura, S. 2002. Macrolide antibiotics: chemistry, biology, and

and chemotherapy, Chicago.

practice. Academic Press.

25. Farmer, S, Li, ZS, Hancock, RE. 1992. Influence of outer

13. Tenson, T, Lovmar, M, Ehrenberg, M. 2003. The mechanism

membrane mutations on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to the

of action of macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B

dibasic macrolide azithromycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.

reveals the nascent peptide exit path in the ribosome. J. Mol.

29:27-33.

Biol. 330:1005-1014.

26. Zuckerman, JM. 2004. Macrolides and ketolides: azithromycin,

14. Leclercq, R. 2002. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and

clarithromycin, telithromycin. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am.

lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical

18:621-649.

implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:482-492.

27. Takashima, H. 2003. Structural consideration of macrolide

15. Vaara, M. 1993. Outer membrane permeability barrier to

antibiotics in relation to the ribosomal interaction and drug

azithromycin, clarithromycin, and roxithromycin in gram-

design. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3:991-999.

negative enteric bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

28. Walsh, F, Willcock, J, Amyes, S. 2003. High-level

37:354-356.

telithromycin resistance in laboratory-generated mutants of

16. Brimacombe CA, Stevens A, Jun D, Mercer R, Lang AS,

Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:345-

Beatty JT. 2013. Quorum-sensing regulation of a capsular

polysaccharide receptor for the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene

transfer agent (RcGTA). Mol. Microbiol. 87:802-817

Page 8 of 8

Source: http://jemi.microbiology.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/Botros%20et%20al..pdf

Contributions of low molecule number and enetics chromosomal positioning to stochastic gene expression Attila Becskei1, Benjamin B Kaufmann1,2 & Alexander van Oudenaarden1 The presence of low-copy-number regulators and switch-like signal propagation in regulatory networks are expected to increasenoise in cellular processes. We developed a noise amplifier that detects fluctuations in the level of low-abundance mRNAs in

PROCEEDINGS, Kenya Geothermal Conference 2011 Kenyatta International Conference Center, Nairobi, November 21-22, 2011 HEALTH SPA TOURISM: A POTENTIAL USE OF SAGOLE THERMAL SPRING IN LIMPOPO PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA Tshibalo, Azwindini Ernest University of South Africa Preller Street, Muckleneuk Ridge, Pretoria ABSTRACT The Sagole Spa thermal spring is located in Limpopo Province, South Africa, and has a water temperature of about 45°C. The spa flourished in the 1980s as a site for recreation and tourism, but its condition declined for various reasons after 1994, which saw the advent of the new democratic government. However, the water temperature and flow rate have remained the same since the 1980s.The research study sought to identify the most beneficial potential development projects for the thermal spring. The following research methods were used to identify the potential projects: literature review, focus group interviews, site visits and observation, and water sample collection and analysis. Health spa tourism was identified as a potentially viable development project for the spa. Some minerals and trace elements with curative power were identified in the thermal water. The environmental, social and economic impacts and the feasibility of establishing the health spa tourism project were assessed. Development costs and potential benefits were also analyzed. It is concluded that health spa tourism can benefit Sagole, a rural area in Limpopo, South Africa.