Cialis ist bekannt für seine lange Wirkdauer von bis zu 36 Stunden. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich deutlich von Viagra. Viele Schweizer vergleichen daher Preise und schauen nach Angeboten unter dem Begriff cialis generika schweiz, da Generika erschwinglicher sind.

Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and metaanalysis

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Aspirin Versus Anticoagulation for Prevention of Venous

Thromboembolism Major Lower Extremity Orthopedic Surgery: A

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Frank S. Drescher, MD1*, Brenda E. Sirovich, MD, MS2, Alexandra Lee, MS3, Daniel H. Morrison, MD, MS4, Wesley H. Chiang, MS2,

Robin J. Larson, MD, MPH2

1Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont;2Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Center for Education, Lebanon, NewHampshire; 3Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University, Miami, Florida; 4Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Sec-tion of Otolaryngology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

BACKGROUND: Hip fracture surgery and lower extremity

screened participants for deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

arthroplasty are associated with increased risk of both

Overall rates of DVT did not differ statistically between aspi-

venous thromboembolism and bleeding. The best pharma-

rin and anticoagulants (relative risk [RR]: 1.15 [95% confi-

cologic strategy for reducing these opposing risks is

dence interval {CI}: 0.68–1.96]). Subgrouped by type of

surgery, there was a nonsignificant trend favoring anticoa-gulation following hip fracture repair but not knee or hip

PURPOSE: To compare venous thromboembolism (VTE)

arthroplasty (hip fracture RR: 1.60 [95% CI: 0.80–3.20], 2 tri-

and bleeding rates in adult patients receiving aspirin versus

als; arthroplasty RR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.49–2.05], 5 trials). The

anticoagulants after major lower extremity orthopedic

risk of bleeding was lower with aspirin than anticoagulants

following hip fracture repair (RR: 0.32 [95% CI: 0.13–0.77], 2

DATA SOURCES: Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing

trials), with a nonsignificant trend favoring aspirin after

and Allied Health Literature, and the Cochrane Library

arthroplasty (RR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.33–1.21], 5 trials). Rates

through June 2013; reference lists, ClinicalTrials.gov, and

of pulmonary embolism were too low to provide reliable

scientific meeting abstracts.

STUDY SELECTION: Randomized trials comparing aspirin

CONCLUSION: Compared with anticoagulation, aspirin

to anticoagulants for prevention of VTE following major

may be associated with higher risk of DVT following hip

lower extremity orthopedic surgery.

fracture repair, although bleeding rates were substantially

lower. Aspirin was similarly effective after lower extremity

extracted data on rates of VTE, bleeding, and mortality.

arthroplasty and may be associated with lower bleedingrisk. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2014;000:000–000.

DATA SYNTHESIS: Of 298 studies screened, 8 trials includ-

C 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

ing 1408 participants met inclusion criteria; all trials

Each year in the United States, over 1 million adults

ity and mortality for patients, as well as substantial

undergo hip fracture surgery or elective total knee or

costs to the healthcare system.6 Although VTE is con-

sidered to be a preventable cause of hospital admis-

improving functional status and quality of life,2,3 each

sion and death,7,8 the postoperative setting presents a

of these procedures is associated with a substantial

particular challenge, as efforts to reduce clotting must

risk of developing a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or

be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

pulmonary embolism (PE).4,5 Collectively referred to

Despite how common this scenario is, there is no

as venous thromboembolism (VTE), these clots in the

consensus regarding the best pharmacologic strategy.

venous system are associated with significant morbid-

thromboprophylaxis," leaving the clinician to selectthe specific agent.4,5 Explicitly endorsed optionsinclude aspirin, vitamin K antagonists (VKA), unfrac-tionated heparin, fondaparinux, low-molecular-weight

*Address for correspondence and reprint requests: Frank Drescher,MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dart-

heparin (LMWH) and IIa/Xa factor inhibitors. Among

mouth, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Veterans Affairs Medical

these, aspirin, the only nonanticoagulant, has been the

Center,(111) 215 North Main Street, White River Junction, VT 05009;Telephone: 802-295-9363; Fax: 802-291-6257; E-mail:

source of greatest controversy.4,9,10

Two previous systematic reviews comparing aspirin

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of

to anticoagulation for VTE prevention found conflict-

this article.

ing results.11,12 In addition, both used indirect com-

Received: February 12, 2014; Revised: May 9, 2014; Accepted: May 20,

parisons, a method in which the intervention and

comparison data come from different studies, and sus-

2014 Society of Hospital Medicine DOI 10.1002/jhm.2224Published online in Wiley Online Library (Wileyonlinelibrary.com).

ceptibility to confounding is high.13,14 We aimed to

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

overcome the limitations of prior efforts to address

our inclusion criteria. We used exploded Medical Sub-

this commonly encountered clinical question by con-

ject Headings terms and key words to generate sets

ducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of

for "aspirin" and "major orthopedic surgery" themes,

randomized controlled trials that directly compared

then used the Boolean term, "AND," to find their

the efficacy and safety of aspirin to anticoagulants for

VTE prevention in adults undergoing common high-risk

Additional Search Methods

We manually reviewed references of relevant articlesand

MATERIAL AND METHODS

ongoing studies or unpublished data. We further

searched the following sources: American College of

Prior to conducting the review, we outlined an

Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence-Based Clinical

approach to identifying and selecting eligible studies,

Practice Guidelines,4,17 American Academy of Ortho-

prespecified outcomes of interest, and planned sub-

paedic Surgeons guidelines (AAOS),5 and annual

group analyses. The meta-analysis was performed

meeting abstracts of the American Academy of Ortho-

according to the Preferred Reporting Items for System-

paedic Surgery,18 the American Society of Hematol-

ogy,19 and the ACCP.20

Study Eligibility Criteria

Two pairs of 2 reviewers independently scanned the

We prespecified the following inclusion criteria: (1)

titles and abstracts of identified studies, excluding only

the design was a randomized controlled trial; (2) the

those that were clearly not relevant. The same reviewers

population consisted of patients undergoing major

independently reviewed the full text of each remaining

orthopedic surgery including hip fracture surgery or

study to make final decisions about eligibility.

total knee or hip arthroplasty; (3) the study compared

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

aspirin to 1 or more anticoagulants: VKA, unfractio-

Two reviewers independently extracted data from

nated heparin, LMWH, thrombin inhibitors, pentasac-

each included study and rendered judgments regarding

charides (eg, fondaparinux), factor Xa/IIa inhibitors

the methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk

dosed for VTE prevention; (4) subjects were followed

for at least 7 days; and (5) the study reported at least1 prespecified outcome of interest. We allowed the use

of pneumatic compression devices, as long as devices

We used Review Manager (RevMan 5.1) to calculate

were used in both arms of the study.

pooled risk ratios using the Mantel-Haenszel methodand random-effects models, which take into account

the presence of variability among included stud-

We designated the rate of proximal DVT (occurring

ies.16,22 We also manually pooled absolute event rates

in the popliteal vein and above) as the primary out-

for each study arm using the study weights assigned in

the pooled risk ratio models.

included rates of PE, PE-related mortality, and all-cause mortality. We required that DVT and PE were

Assessment of Heterogeneity and Reporting Biases

diagnosed by venography, computed tomography

We assessed statistical variability among the studies

(CT) angiography of the chest, pulmonary angiogra-

contributing to each summary estimate and considered

phy, ultrasound Doppler of the legs, or ventilation/

studies unacceptably heterogeneous if the test for het-

perfusion scan. We allowed studies that screened par-

erogeneity P value was <0.10 or the I2 exceeded

ticipants for VTE (including the use of fibrinogen leg

50%.14,16 We constructed funnel plots to assess for

publication bias but had too few studies for reliable

A bleeding event was defined as any need for post-

operative blood transfusion or otherwise clinically sig-nificant bleeding (eg, prolonged postoperative wound

Subgroup Analyses

bleeding). We further defined major bleeding as the

We prespecified subgroup analyses based on the indica-

requirement for blood transfusion of more than 2 U,

tion for the surgery: hip fracture surgery versus total

hematoma requiring surgical evacuation, and bleeding

knee or hip arthroplasty, and according to class of anti-

into a critical organ.

coagulation used: VKA versus heparin compounds.

Study Identification

We searched Medline (January 1948 to June 2013),

Results of Search

Cochrane Library (through June 2013), and CINAHL

Figure 1 shows the number of studies that we eval-

(January 1974 to June 2013) to locate studies meeting

uated during each stage of the study selection process.

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

FIG. 1. Flow diagram of the search results. ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; AOOS, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; ASH; AmericanSociety of Hematology; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

After full-text review, 8 randomized trials met all

was 7 to 21 days. Clinical follow-up extended up to 6

months after surgery. Patients in all included studieswere screened for DVT during the trial period by I-

fibrinogen leg scanning,23,25–27 venography,24,28 or

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 8 included

ultrasound29,30; some trials also screened all partici-

randomized trials. All were published in peer-reviewed

pants for PE with ventilation/perfusion scanning.27,28

journals from 1982 through 2006.23–30 The trialsincluded a combined total of 1408 subjects, and took

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

place in 4 different countries, including the United

Only 3 studies described their method of random

States,24,26,28–30 Spain,23 Sweden,27 and Canada.25

sequence generation,24–26 and 2 studies specified their

Enrolled patients had a mean age of 76 years (range,

method of allocation concealment.25,26 Only 1 study

74–77 years) among hip fracture surgery studies and

used placebo controls to double blind the study arm

66 years (range, 59–69 years) among elective knee/hip

assignments.25 We judged the overall potential risk of

bias among the eligible studies to be moderate.

Pneumatic compression devices were used in addi-

tion to pharmacologic prevention in 2 studies.29,30

Rate of Proximal DVT

The different classes of anticoagulants used included

Pooling findings of all 7 studies that reported proxi-

warfarin,26,28,30 heparin,23,27 LMWH,29 heparin or

mal DVT rates, we observed no statistically significant

warfarin,24 and danaparoid.25 Treatment duration

difference between aspirin and anticoagulants (10.4%

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Included Studies

Aspirin (Total/Day)

Heparin or warfarin

NOTE: Abbreviations: N/A, not available; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

*Gent reported venous thromboembolism events in the subset of screened patients only: aspirin: n 5 84, danaparoid: n 5 88.

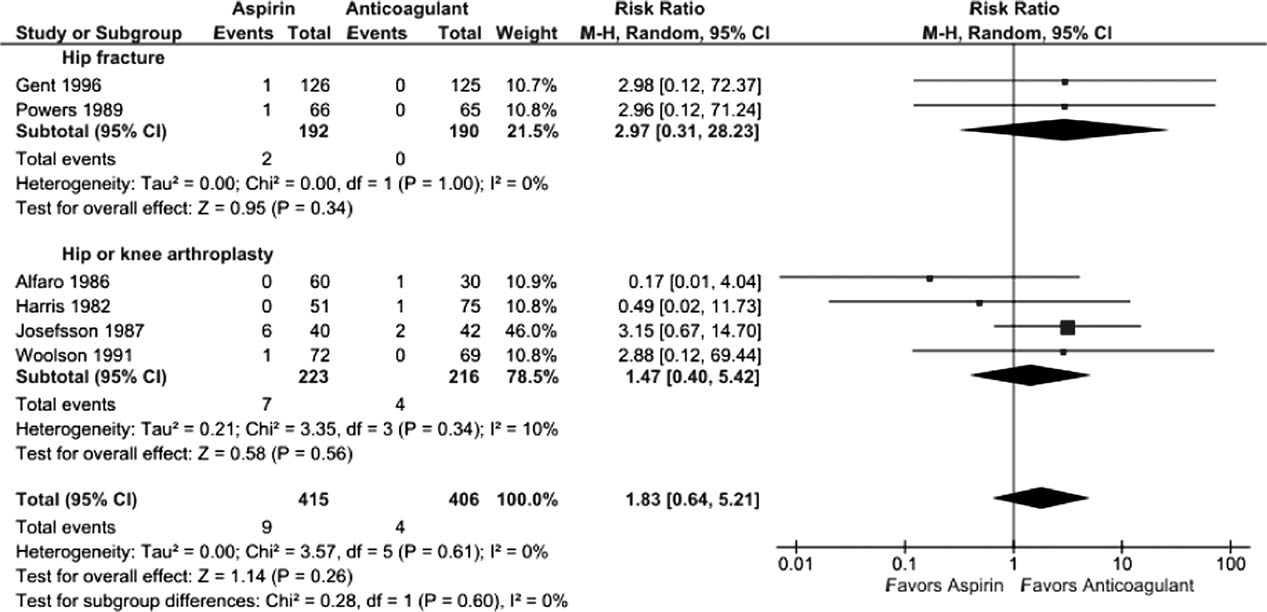

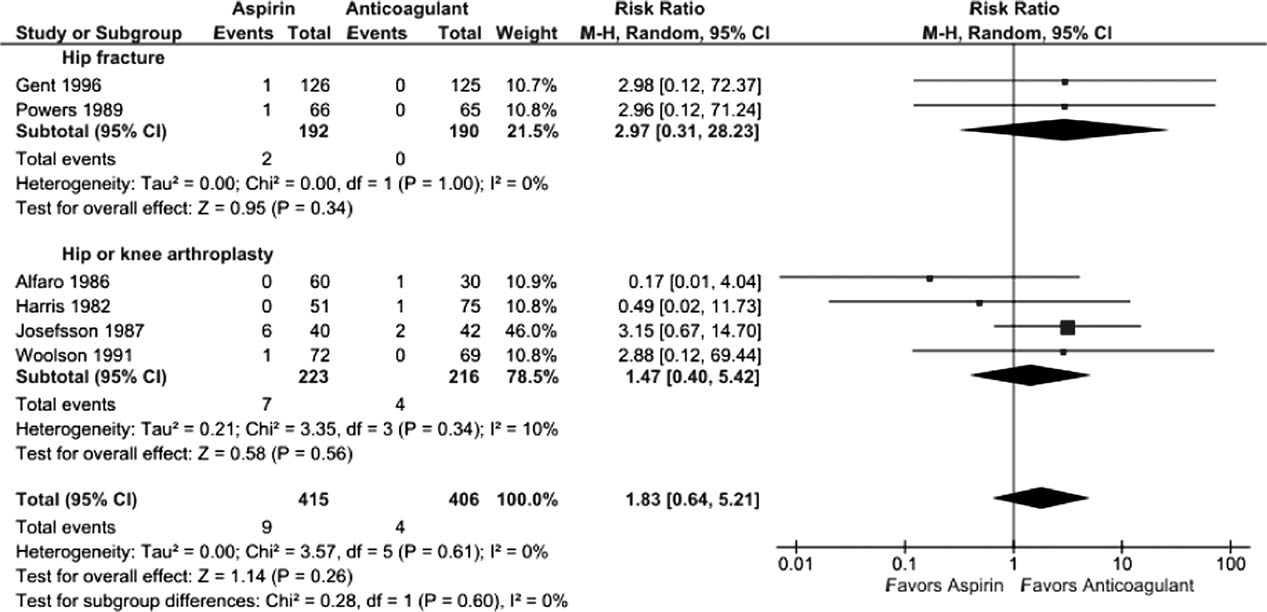

FIG. 2. Effects of aspirin versus anticoagulation on rates of proximal deep venous thrombosis. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

vs 9.2%, relative risk [RR]: 1.15 [95% confidence

0.9%, RR: 1.83 [95% CI: 0.64, 5.21], I2 5 0%). The

interval {CI}: 0.68-1.96], I2 5 41%). Although rates

very small number of events rendered extremely wide

did not statistically differ between aspirin and anticoa-

95% CIs in operative subgroup analyses (Figure 3).

gulants in either operative subgroup, there appearedto be a nonsignificant trend favoring anticoagulation

Rates of All-Cause Mortality

after hip fracture repair (12.7% vs 7.8%, RR: 1.60

Only 2 trials, both evaluating aspirin versus anticoa-

[95% CI: 0.80-3.20], I2 5 0%, 2 trials) but not

gulation following hip fracture repair, reported death

following knee or hip arthroplasty (9.3% vs 9.7%,

events, both after 3 months follow-up.25,26 Pooling

RR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.49-2.05], I2 5 49%, 5 trials)

these results, there was no statistically significant dif-

ference (7.3% vs 6.8%, RR: 1.07 [95% CI: 0.51–2.21], I2 5 0%).

Rate of Pulmonary Embolism

Just 14 participants experienced a PE across all 6 tri-

Pooling all 8 studies, aspirin was associated with a stat-

als reporting this outcome (aspirin n 5 9/405 versus

istically significant 48% decreased risk of bleeding

anticoagulation n 5 5/415). Although PE was numeri-

events compared to anticoagulants (3.8% vs 8.0%, RR:

cally more likely in the aspirin group, this difference

0.52 [95% CI: 0.31–0.86], I2 5 8%). When subgrouped

was not statistically significant (overall: 1.9% vs

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

FIG. 3. Effects of aspirin versus anticoagulants on pulmonary embolism rates. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

statistically significantly lower in the aspirin group fol-

anticoagulants. This benefit, however, was associated

lowing hip fracture (3.1% vs 10%, RR: 0.32 [95% CI:

with a nonsignificant increase in screen-detected proximal

0.13–0.77], I2 5 0%, 2 trials); however, the observed

DVT. Conversely, among patients undergoing knee or hip

trend favoring aspirin was not statistically significant

arthroplasty, we found no difference in proximal DVT

following arthroplasty (3.9% vs 7.8%, RR: 0.63 [95%

risk between aspirin and anticoagulants and a possible

CI: 0.33–1.21], I2 5 14%, 5 trials) (Figure 4).

trend toward less bleeding risk with aspirin. The rarity of

Five studies reported major bleeding; event rates

pulmonary emboli (and death) made meaningful compari-

were low and no statistically significant differences

sons between aspirin and anticoagulation impossible for

between aspirin and anticoagulants were observed(hip fracture: 3.5% vs 6.3%, RR: 0.46 [95% CI:

either type of surgery.

Our systematic review has several strengths that dif-

5 0%, 2 trials; knee/hip arthroplasty:

2.1% vs 0.6%, RR: 2.86 [95% CI: 0.65–12.60],

ferentiate it from previous analyses. First, we only

included head-to-head randomized trials such that all

5 0%, 3 trials).

included data reflect direct comparisons between aspi-rin and anticoagulation in well-balanced populations.

Subgroup Analysis

Conversely, both recent reviews11,12 were based on

Rates of proximal DVT did not differ between aspirin

indirect comparisons, a type of analysis in which data

and anticoagulants when subgrouped according to

for the intervention and control arms are taken from

anticoagulant class (aspirin vs warfarin: 9.7% vs

different studies and thus different populations. This

10.7%, RR: 0.90 [95% CI: 0.56–1.45], I2 5 0%, 3

methodology is not recommended by the Cochrane

trials; aspirin vs heparin: 10.5% vs 7.9%, RR: 1.37

Collaboration13,14 because of the increased risk of an

[95% CI: 0.47–3.96], I2 5 44%, 4 trials) (data not

unbalanced comparison. For example, Brown and col-

leagues' meta-analysis, which pooled data from

Bleeding rates were lower with aspirin when sub-

selected arms of 14 randomized controlled trials,

grouped according to type of anticoagulant, but the

found the efficacy of aspirin comparable to that of

finding was only statistically significant when com-

anticoagulants, but all aspirin subjects came from a

pared to VKA (aspirin vs VKA: 4.2% vs 11.1%, RR:

single trial of patients at such low risk of VTE that a

0.43 [95% CI: 0.22–0.86] I2 5 0%, 4 trials; aspirin vs

placebo arm was considered justified.31 Similarly, in

heparin: 3.7% vs 7.7%, RR: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.15–

the indirect comparison of Westrich and colleagues,12

1.28], I2 5 44, 4 trials) (data not shown).

which found anticoagulation superior to aspirin, thelikelihood of an unbalanced comparison was further

heightened by their inclusion of observational studies,

We found the balance of risk versus benefit of aspirin

with the attendant risk of confounding by indication.

compared to anticoagulation differed markedly according

Our systematic review further differs from previous

to type of surgery. After hip fracture repair, we found a

analyses by examining both beneficial and harmful

68% reduction in bleeding risk with aspirin compared to

clinical outcomes, and doing so separately for the 2

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

FIG. 4. Effects of aspirin versus anticoagulants on bleeding rates (any significant bleed). CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

most common types of major orthopedic lower

and intermittent pneumatic compression devices are

extremity surgery. This allowed us to discover impor-

standard prophylaxis against postoperative VTE. In

tant differences in the comparative efficacy (benefit vs

fact, only 2 trials used concomitant pneumatic com-

harm) of aspirin versus anticoagulants across different

pression devices, and none treated patients longer

procedure types. Finding that aspirin may have lower

than 21 days, the current standard being up to 35

efficacy for preventing VTE following hip fracture

days.4 Although these limitations may affect overall

repair than arthroplasty may not be surprising in light

event rates, this bias should be balanced between

of the nature of the 2 procedures, the disparate mean

ages typical of patients who undergo each procedure,

randomized controlled trials.

and the underlying trauma in hip fracture patients.

What is a clinician to do? Based on our findings,

The limitations of our review largely reflect the

current guidelines recommending aspirin prophylaxis

quality of the studies we were able to include. First,

against VTE as an alternative following major lower

our pooled sample size remains relatively small, mean-

extremity surgery may not be universally appropriate.

ing that observed nonsignificant differences between

We found that although overall bleeding complica-

aspirin and anticoagulation groups (eg, a nonsignifi-

tions are lower with aspirin, concerns about poor effi-

cant 60% increased risk of DVT for aspirin after hip

cacy remain, specifically for patients undergoing hip

repair, 95% CI: 0.80–3.20) could reasonably reflect

fracture repair. Although some have suggested that

up to 3-fold differences in DVT risk and 5-fold differ-

aspirin use be restricted to low risk patients, this strat-

ences in PE rates. Second, screening for DVT, which

egy has not been experimentally evaluated.33 On the

is neither recommended nor common in clinical prac-

other hand, switching to aspirin after a brief initial

tice, was used in all studies. Reported DVT incidence,

course of LMWH may be an approach warranting

therefore, is undoubtedly higher than what would be

further study, in light of a recent randomized con-

observed in practice; however, the effect on the direc-

trolled trial of 778 patients after elective hip replace-

tion and magnitude of observed relative risks is unpre-

ment, which found equivalent efficacy using 10 days

dictable. Third, included studies used a wide range of

of LMWH followed by aspirin versus additional

aspirin doses, as well as a variety of anticoagulant

LMWH for 28 days.34

types. Although supratherapeutic aspirin doses are

We are able to be more definitive, based on our

unlikely to confer additional benefit for venous throm-

study of best available trial data, in making recom-

boprophylaxis, they may be associated with excess

mendations to investigators embarking on further

bleeding risk.32 Finally, several of the studies were

study of optimal VTE prophylaxis following major

conducted more than10 years ago. Given changes in

orthopedic surgery. First, distinguishing a priori

treatment practices, surgical technique, and prophy-

between the 2 major types of lower extremity major

laxis options, the findings of these studies may not

orthopedic surgery is a high priority. Second, both

reflect current practice, in which early mobilization

bleeding and thromboembolic outcomes must be

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

evaluated. Third, only symptomatic events should be

12. Westrich GH, Haas SB, Mosca P, Peterson M. Meta-analysis of

thromboembolic prophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone

used to measure VTE outcomes; clinical follow-up

Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):795–800.

must continue well beyond discharge, for at least 3

13. Song F, Loke YK, Walsh T, Glenny A-M, Eastwood AJ, Altman DG.

months to ensure ascertainment of clinically relevant

Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evalu-ating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews.

should be standardized and represent the standard of

14. Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews

of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available at:

care, including early immobilization and mechanical

Accessed June 2013.

15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; the PRISMA Group. Pre-

ferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the

In summary, although definitive recommendations

PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

for or against the use of aspirin instead of anticoagu-

16. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for

reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evalu-

lation for VTE prevention following major orthope-

ate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med.

dic surgery are not possible, our findings suggest

17. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous throm-

that, following hip fracture repair, the lower risk of

boembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based

bleeding with aspirin is likely outweighed by a prob-

clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

able trend toward higher risk of VTE. On the other

18. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical

hand, the balance of these opposing risks may favor

patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9thed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical prac-

aspirin after elective knee or hip arthroplasty. A

tice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

comparative study of aspirin, anticoagulation, and a

19. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts-Blood. Available at:

hybrid strategy (eg, brief anticoagulation followed by

Accessed June 2013.

aspirin) after elective knee or hip arthroplasty should

20. CHEST Publications Meeting Abstracts. Available at:

be a high priority given our aging population and

increasing demand for major orthopedic lower

21. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collabo-

extremity surgery.

ration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ.

2011;343:d5928.

22. Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.1. Copen-

hagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Col-

laboration; 2011.

The authors thank Dr. Deborah Ornstein (Associate Professor of Medi-

23. Alfaro MJ, Paramo JA, Rocha E. Prophylaxis of thromboembolic dis-

cine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Section of Hematology

ease and platelet-related changes following total hip replacement: a

Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, Lebanon, New Hampshire) for

sparking the idea for this systematic review.

Thromb Haemost. 1986;56(1):53–56.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

24. Harris WH, Athanasoulis CA, Waltman AC, Salzman EW. High and

low-dose aspirin prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic diseasein total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(1):63–66.

25. Gent M, Hirsh J, Ginsberg JS, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparinoid

1. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available at: http://

orgaran is more effective than aspirin in the prevention of venous

hcupnet.ahrq.gov. Accessed June 2013.

thromboembolism after surgery for hip fracture. Circulation. 1996;

2. March LM, Cross MJ, Lapsley H, et al. Outcomes after hip or knee

replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study

26. Powers PJ, Gent M, Jay RM, et al. A randomized trial of less intense

comparing patients' quality of life before and after surgery with age-

postoperative warfarin or aspirin therapy in the prevention of venous

related population norms. Med J Aust. 1999;171(5):235–238.

thromboembolism after surgery for fractured hip. Arch Intern Med.

3. Ng CY, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. Quality of life and functional out-

come after primary total hip replacement. A five-year follow-up.

27. Josefsson G, Dahlqvist A, Bodfors B. Prevention of thromboembolism

J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(7):868–873.

in total hip replacement. Aspirin versus dihydroergotamine-heparin.

4. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in

Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58(6):626–629.

orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of

28. Lotke PA, Palevsky H, Keenan AM, et al. Aspirin and warfarin for

thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-

thromboembolic disease after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop

based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–

Relat Res. 1996;(324):251–258.

5. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). American

29. Westrich GH, Bottner F, Windsor RE, Laskin RS, Haas SB, Sculco

Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on pre-

TP. VenaFlow plus Lovenox vs VenaFlow plus aspirin for throm-

venting venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elec-

boembolic disease prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthro-

tive hip and knee arthroplasty. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of

plasty. 2006;21(6 suppl 2):139–143.

Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2011. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/

30. Woolson ST, Watt JM. Intermittent pneumatic compression to pre-

research/guidelines. Accessed June 2013.

vent proximal deep venous thrombosis during and after total hip

6. MacDougall DA, Feliu AL, Boccuzzi SJ, Lin J. Economic burden of

replacement. A prospective, randomized study of compression alone,

deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post-thrombotic syn-

compression and aspirin, and compression and low-dose warfarin.

drome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(20 suppl 6):S5–S15.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(4):507–512.

7. Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hos-

31. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with

pital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc

low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet.

8. Lindblad B, Eriksson A, Bergqvist D. Autopsy-verified pulmonary

32. Yu J, Mehran R, Dangas GD, et al. Safety and efficacy of high- versus

embolism in a surgical department: analysis of the period from 1951

low-dose aspirin after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in

to 1988. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):849–852.

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS-AMI

9. Colwell CW Jr. What is the state of the art in orthopaedic thrombo-

(Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute

prophylaxis in lower extremity reconstruction? Instr Course Lect.

Myocardial Infarction) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(12):

10. Stewart DW, Freshour JE. Aspirin for the prophylaxis of venous

33. Intermountain Joint Replacement Center Writing Committee. A pro-

thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients: a comparison

spective comparison of warfarin to aspirin for thromboprophylaxis in

of the AAOS and ACCP guidelines with review of the evidence. Ann

total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;27:e1–e9.

34. Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER, et al. Aspirin versus low-

11. Brown GA. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major ortho-

molecular-weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism pro-

paedic surgery: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials.

phylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern

J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 supplement 1):77–83.

An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 00 No 00 Month 2014

Source: https://www.manamed.net/docs/clinicals/DrescherAspirin.pdf

Foreword from Chairperson The summary presentation of SEBAC-Nepal's Social Undertakings pertaining to 2015 AD has come to Publication. It is extremely a jubilant occasion to share & cherish the meaningful outcomes and the degree of social economic transformation implanted in the social milieu entailing excluded, deprived, marginalized, vulnerable, resource poor, exploited

The Top 101 Superfoods That Fight Aging The Best Youth-Enhancing Foods, Spices, Herbs, and Other Tricks to Look and Feel 10 Years Younger, Protect Your Skin, Muscles, Organs and Joints to SLOW Aging By Catherine Ebeling RN BSNand Mike Geary, Certified Nutrition Specialist, DISCLAIMER: The information provided by this book and this company is not a substitute for a face-to-face consultation with your physician, and should not be construed as individual medical advice. If a condition persists, please contact your physician. This book is provided for personal and informational purposes only. This book is not to be construed as any attempt to either prescribe or practice medicine. Neither is the book to be understood as putting forth any cure for any type of acute or chronic health problem. You should always consult with a competent, fully licensed medical professional when making any decisions regarding your health. The authors of this book will use reasonable efforts to include up-to-date and accurate information on this book, but make no representations, warranties, or assurances as to the accuracy, currency, or completeness of the information provided. The authors of this book shall not be liable for any damages or injury resulting from your access to, or inability to access, this book, or from your reliance upon any information provided in this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language, in any form, by any means, without the written permission of the author.